Braid, the 2008 videogame by Jonathan Blow, widely heralded as the first Xbox Arcade indie game and the dawn of a new era of artistic expression in videogames and the newly democratised marketplace, is in an uncited claim on its Wikipedia page, in contention as ‘one of the best videogames of all time,’ which suggests that this little indie game is very important and smart and deep, like other best videogames of all time on the wikipedia list, like Ninja Gaiden.

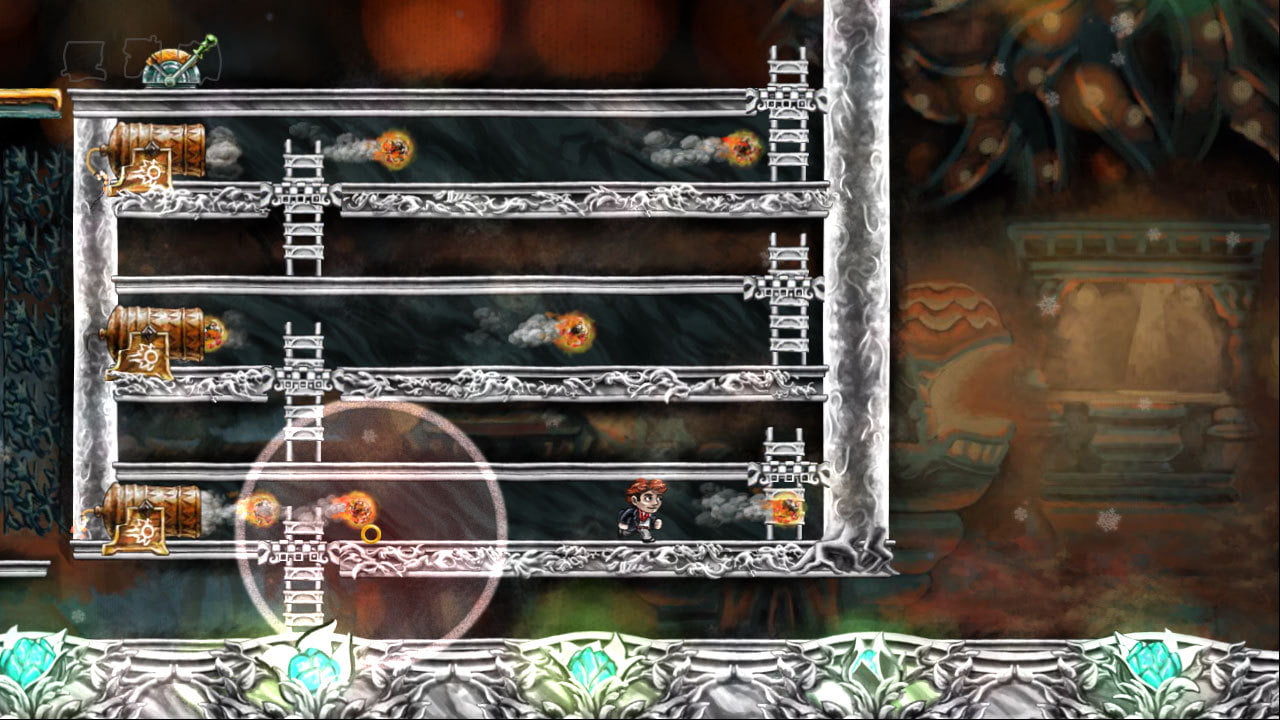

For obligatory game-as-game-context, Braid is a side-scrolling puzzle platformer game with your classic runny-jumpy-climby, a beautiful hand-painted art style and puzzles that focus on an engine that can do endless, smooth rewinding of every game entity all at once. This has a lot of clever design in it, and thanks to the endless rewinding, you can design the whole game around really challenging puzzles knowing you can always reset them and try again.

It’s decent.

It’s fine.

It’s regularly quite cheap, and it definitely isn’t overpriced.

Spoilers for Braid, ahead.

Normally I wouldn’t bother talking about Braid because it is, at best, decent. It’s a neat little puzzle game, but I felt that it was a very obvious little story when you engaged with it critically. As a videogame, it was definitely a cut above aesthetically, had a fun challenging difficulty curve, and if you had to review the whole game in a day, probably a pretty incomprehensible story that looked very deep.

And then the Author had to rise from the grave.

“In the year 2018, all art had to be about either gender or capitalism, and this was supposed to make art more interesting.”

– Johnathan Blow

Around April 2018, I was offhandedly brought to consider that Braid was not meant to be about gender. Blow had been in a conversation where he suggested criticisms of games as being about gender and capitalism was boring, which seemed really weird to me in this context, since, well, he made Braid.

I have a conflicted position on Jonathan Blow in that I am an adult human and so is he and yet for some reason I feel like I have to be careful reacting to his positions as if he is somehow incapable of saying stupid ding-dong words out of his flappy mouth-hole. Running through the list of why I think Jonathan is a sillyboots would be a distraction, but I think it’s very important to just underscore that I’m approaching Braid as a text where I don’t think the author is actually particularly well-informed about what the text is doing.

Now, there are plenty of reasons to do this – the author, after all, may have had intention, but the author is also a vessel for subconscious biases. Also, games are paratextual – the text is full of this thing called play, where you, the player of the game, get to change the way the text is being formed. The classical idea of the death of the author is really well established too, but I need to repeat, the main reason I employ the death of the author talking about Braid is because I don’t think Jonathan Blow is a particularly good person to talk critically about games.

Is that coming through clearly? I think Jonathan Blow is silly. He is the indie David Cage. He has convinced people around him that he seems smart, so he must be smart, and that smartness voices a very narrow style rather than an actual depth.

Let’s then talk, knowing that this is just my interpretation, and it is not the interpretation, and that my interpretation is valid (and so is Mr Blow’s).

To me, Braid is a story about boys.

Braid is a story about boys, and about the ways boys are, in this world, broken.

First, the story is framed as a videogame. There’s a very deliberate choice to make Braid as a videogame being played as the story of a boy. There’s a constant narrative of correcting women, of arguing against women who are either trying to respect themselves or connect to the protagonist. The braid of the title is referenced in the capacity of a mother trying to keep her child from reaching out for something that would hurt someone.

The whole of this story is told through little books, separated out from the game play, told in deliberately disjointed, achronic ways. The gameplay shows you repeated loops, and dreamlike conglomerated worlds, worlds that only make sense as videogame levels, where a videogame serves as the metaphor for a flipping videogame. The story then repeats on itself; there are numerous attempts to make snese of the same basic puzzle, as the world the puzzle is from gets more complicated.

The game is full of references, to Sonic the Hedgehog and to Super Mario Bros, and the eventual plot revelation of the first run through the game is to confront that you aren’t actually the good boy you thought you were, and that the girl you were pursuing was running away from you and then into the arms of someone she wanted more than you. And then, the game gives you a chance to restart, and try again, and give you a different take on it. What if that wasn’t the way the story went, the game asks, what if something else was the case.

So you replay the game in the hopes that maybe it’s not really a story about you ignoring women. And you play through it again, ignoring the women in the story segments who do not get to appear, and you ignore their opinions and you ignore the way their story bits are segmented off and you find yourself again at that last level and you play through it again and no, find, again, it’s the same story. You’re still the bad guy. And you think about what that means and struggle through the last story beats that have nothing to do with what you just saw.

And you try again.

And again.

And eventually you find the stars.

And suddenly you have a new course of action. You have to look at the levels all over again and find maybe, the thing in them that you missed. You have look up and down and back again, at this ever-increasing world of complexity. Sometimes you have to stand still, on your own, completely ignoring everything, doing nothing but playing this videogame in the least fun, least engaging way possible, for hours, and that gets you a star. And sometimes you have to delay gratification and show you’re smart, by not solving a problem as soon as you can, and that gets you a star. And so on and so forth, as you steadily get all the stars, and then you get the new ending, and find that, in fact, you can get the girl. You got the girl because you were smart enough, and you knew she wasn’t the girl, she was, she was…

Then begins the final stage of the game, where you try to rationalise what you just played and what it means. All that stuff about women and being ignored and ignoring women and discarded wedding rings and the woman who runs from you and the ruined relationships, that’s not what the story is really about. You, smart game player, eventually have to work out the story is about the nuclear bomb, or whatever.

Basically this is a game about ignoring all the ways you’re treating women in your life so you can prove that the real problem is how clever you are.

Blow has spoken, he says, about the potential of games to be more. This is an impressive sounding, but it’s a hollow deepity – because in how he talks about his own games, it becomes pretty clear that Blow doesn’t actually know what games already are, let alone what they could be. And thanks to the vaguaries of who gets to be heard in this media landscape where having $200,000 to drop on your weird little indie game project is itself, a function of capitalism and its ability to randomly select winners and losers based on existing privilege superstructures, it’s kind of hard to argue that Braid is not, down to its very soul, a game about gender and capitalism.

It’s a shame, because if this guy who is a luminary and well-financed voice in the videogame scene, if this ‘serious voice’ on the subject seems to be so unaware of the things he’s bringing to the table, that sort of suggests to me that he’s not getting a lot of variety in the things he’s hearing in his own media landscape.

Dude could benefit from some more diverse voices, is what I’m saying.