Thinking about Blackthorne a lot lately.

Content Warning: I’m going to talk about the recent news pertaining to Blizzard. I don’t intend to go over the specifics of any incident, but this one is a downer.

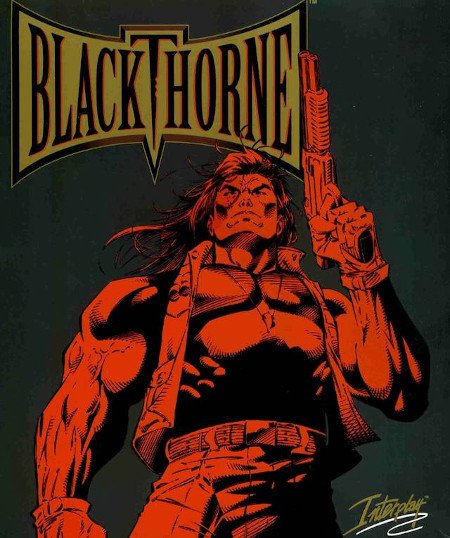

Blackthorne or Blackhawk depending on who you ask, is a 1992 adventure platform game made by a company that was, depending on the pirated copy you downloaded, named either Blizzard or Silicon Synapse. It was made by the people who had an existing pedigree on that very piratable one-disk-wonder The Lost Vikings.

The game was cool in a very embarrassing way in hindsight. Like, this character is a jeans-and-vest wearing probably-Native-American dude with a pump action shotgun that he fired one handed from the hip and could shoot behind himself all nice and casual. It was an isekai story (man, that’s coming up a lot) where you were whisked away to save the day against an enemy who was absolutely adamant that you, yes, you, were the only thing that could stop him despite you being like, off in another dimension.

It wasn’t a great plan.

I also remember the game kinda fondly. Not particularly amazing – it was on every platform that could uh, platform. I never finished it, and finishing it was just a result of solving all the puzzles – for all that the game had you running around with a shotgun and throwing bombs, it was really a lot more like a puzzle game in the skin of a platformer. There was a very limited sort of timing puzzle that constituted ‘combat’ but largely, this wasn’t… well, it wasn’t a game about making snap decisions in combat. It was just a step platformer, in the vein of Prince of Persia, but without that same game’s sense of flow and a shotgun.

I think about it, because I don’t know why I think about it fondly.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Blizzard, as a company lately. I’ve been thinking about them steadily for months, years really, as I examine my relationship to games and games companies. It isn’t that games are primarily moral extrusions from companies, because every gaming industry is composed of scabs we kind of admit we don’t want to pick at right now. It’s that every game in every company made above a certain budget is inevitably being made by destroying human lives through crunch. It’s that every major company, every major brand, has some degree of dreadful problems in how they treat people.

I sometimes like to describe Blizzard as a company that’s great at polishing things. That the games they make are long on things like refined interfaces and satisfying choices but very shallow on things like systems and themes. It’d be nice if I could talk about that and have it be it, you know? Like, oh look, there’s the metaphor; Blizzard are good at a superficial surface but underneath it, it’s all hollow. That’s a conclusion that follows from things that we all know and makes it look like my insight into their game design has some special predictive power and I get to be clever and that’s that.

It is a model of criticism that looks clever, with interlocking pieces, and it is ultimately completely wrong.

The way that Blizzard’s culture of social violence, racism and misogynoir permeated it for years is not some gameplay notion to be extrapolated. It was not the work of some big gamethink to explain that maybe they shouldn’t be proud of ‘the Cosby room.’ I could draw, if I wanted to, a line between the way that bad game design often flows from unempathic understanding of people, and how that reflects in how Blizzard makes games, but that sells short the work of all the people who aren’t making the games and are causing the problems, and all the people who are making the games and aren’t causing the problems.

It’s not as simple as ‘Blizzard, the company is trash.’ Blizzard, the organisation. Blizzard, the corporation. Blizzard, the system, that’s trash. And that trashy system has adorned itself about with the hard work of a lot of people to please, if you would be so kind, pay attention to all of us as one.

It is a thing I think about a lot.

I have this idea that I could say, confidently, and people would think I was smart for it; the idea is comforting and reassuring, and gratifying as to my personal preferences; it explains the work of a company and the attitude of its makers; and all I would have to do to breathe it into the world and have it be heard by people who would trust me, is to be confidently wrong.