I have said, in the past, that the work of Sir Terry Pratchett is ‘funny, witty, satirical and as serious as a heart attack.’ There’s this particular period of oh I dunno, immediately post-Thatcherite Britain which seemed to bring out people who were very good at making you laugh about things like how immensely and completely screwed you all were in a surveillance state with a corrupt media apparatus, I wonder why.

One such work was 1994’s Beneath A Steel Sky, a game that came out in that time when spoken audio and cutscenes were a special feature that would sell the CD-ROM copy of a game. The game fit without those scenes on a few disks, which were comparatively easy to pirate, and it was also relatively easy to play without much in the way of copy protection problems, which meant that the CD-ROM version, with its illustrated comic book pages, backstory on the manual file, and gosh-wow-sugoi cutscenes of 3d rendered helicopters was a thing that you went to someone’s house to watch like it was a special movie event, and the disk version was the one you got swapped in the playground.

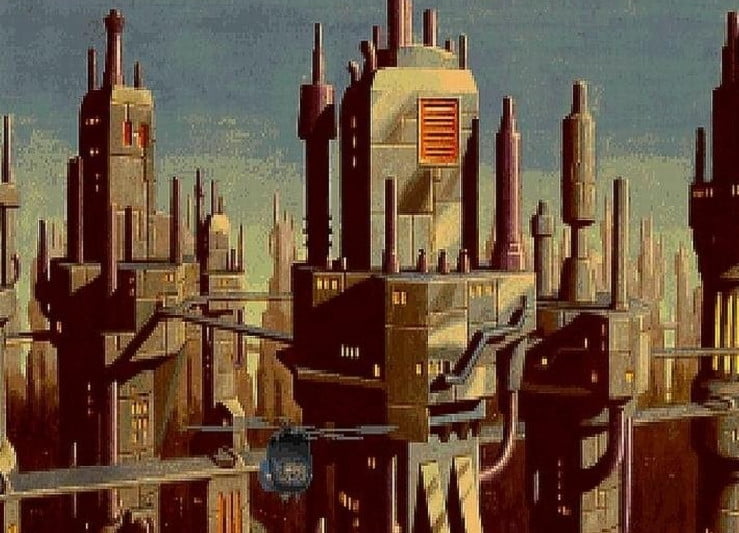

Beneath A Steel Sky tells the story of Robert Foster, an outsider from the wilds of the Outback, who is captured and taken to Union City, whose spires and towers hold and contain a worker population that one day dream of earning enough money to be able to get down to ground level. Workers and their work are kept up high, meaning that to travel down towards the ground requires elevator access, and through these spires, large, dense populations are kept under control. The closer you are to the ground, the more wealth you have, until eventually you can get down out of the towers, reach the soil of the actual world, log off, and perhaps finally, touch grass.

Foster gets kidnapped from the Outback at gunpoint, his home is destroyed with a nuke, and then the helicopter he’s arrived in crashes, leaving you to escape into the bowels of this dreadful machinery, seeking answers for how you got here, why they wanted you, why this world is the way it is, and what now now that your life has been destroyed. You have a circuit card that holds your only friend left in the world, an AI named Joey, and that’s… it. There’s a guard down those stairs and he’ll kill you.

Work it out.

Normally I don’t do this when I talk about games old enough to vote then get sick of trying to vote because all the politicians are the same, man, but I’m actually putting up a Spoiler Warning here. Beneath A Steel Sky is free on GoG and Steam, and if you’re at all interested in this kind of game and you’ve never played it before, I do recommend you try it out. Get a guide so you can refer to it when you get frustrated trying to work out the game’s sense of logic, but otherwise, just soak in the mood of one of the great cyberpunk videogames of the 1990s, and come back here after.

I’m not a believer in spoilers ruining a work, but I do think that Beneath A Steel Sky is much, much funnier and cleverer than my explication of it could be. I’d rather you get in the choir so I can preach to you.

I remarked earlier in the month that I saw this game as duelling with The Dig, where ‘real’ talent for ‘serious’ media got involved and elevated this mere videogame. In this case, the talent is David Gibbons, the artist behind Watchmen and For The Man Who Has Everything. Now this is partly because Gibbons seems to largely keep his mouth shut, but he’s at least not got a ‘controversies’ section on his Wikipedia page, so that’s not nothing.

This was a big deal, like look, that’s a Serious and Important Adult Person making a videogames, and setting aside that we’re also talking about someone whose key work includes Why Do We Even Have Superman Comics and Why Superman Would Suck IRL Comics, you might be able to see this work without realising it was Gibbons at first. It isn’t the same vivid starkness you see of his print work, because to make this game, Gibbons effectively learned an entirely new visual language. The demands of the sprites and the backgrounds were different, and so Gibbons learned them and executed on them. The result is not ‘David Gibbons, Comic Artist made a videogame,’ and more ‘A videogame whose visual language was developed by Videogame Artist David Gibbons.’ Things like sprite collision with backgrounds, mixing palettes, muted and emphasised colours to highlight the three dimensionality of a space all things that Gibbons had to create and structure, and then those worlds were breathed full of life by Revolution.

It works, too, because this game is, in the specific kind of low-resolution 320×200 mapped out pixel art, gorgeous. Things are detailed with a tiny number of pixels to their name, but the art still wants to be extraordinarily detailed, with lots of fine work to create a varied visual environment and set a tone for each area. It is fiddly, no lies – there are more than a few pixel hunt situations and there’s no forgiving it. It’s weird to think that this game predates Simon The Sorcerer 2, with its ‘press this button to highlight all the interactables’ tech, and that this game owes its existence to other videogames: Revolution wanted to make a game that stood somewhere between Sierra’s ‘earnest’ stories like Kings Quest VI and Lucasart’s slapstick comedy games like Day of the Tentacle.

The legitimacy that Gamers still seek, we sought in the 90s, and if you play a game like Beneath a Steel Sky you might think ‘ah, yes, this, this is where we get that brilliance.’ But Gibbons wasn’t there to make the story and the narrative and all of its pieces: Gibbons invented the look of Union city and the developers worked from that. It’s just that they already had a great idea, they already had a world that worked and a story to tell in that space, and the best way to do that was with a videogame.

You can’t spend twenty minutes in a movie bickering with a foreman about a misunderstanding that you have to tease out in the back of your head. You can do it in a TV series, but then you kind of have to parcel that out — you need to make it so that dicking around works in the specific context of that one episode. But videogames, they let you inhabit the experience of the character, and spend as much or as little of that time dicking around as you want, as you need to stimulate the forward progress that you unconsciously may want. It’s a slow boil, and you’re the one in the pot. At a certain point, you’re just pushing forward to work out what happens next, even when the game is ridiculously unfair bullshit.

That slow boil rewards the way Beneath a Steel Sky is structured as well, with the opening being extremely dark comedy, and slowly but steadily getting a little less comedic, a little less, a little less, then bam you’re suddenly wading waist deep in cyberpunk body horror. When you stand at the end of the game looking back there’s this veritable festival of horrible things that you were kind of accepting as Funny Quirky Setting details, but once you’re standing surrounded by Meat Moss and tanks of Other Versions Of Things Like You, you can feel how deeply fucked up this world is and has become.

Lovecraftian horror is often about repulsion of the self – look, no, don’t look at me like that I’m going somewhere here, shut up. Point is that one of the low key things that kept Lovecraft up at night was the importance of his own body, and how there were things he imagined that mattered more than the body, that he was more than his flesh and that there was something inherent about him that should matter to the world and that it didn’t was part of the horror. It is a horror of bodies and minds.

And the game keeps you paying attention to that with fun and funny jokes, constantly.

Remember?

Joey.

Joey is a mind that you carry around and attach to bodies.

I feel like Joey is probably a lot of people’s favourite character, both because he’s just very funny but also because even when he’s shown as being some variety of petty dick, he’s still a really good friend, who fights to protect you, and when he makes mistakes they are, also, yes, extremely funny. Joey’s a peer, he talks at your level, he treats you like you’re a person like him, even though he will joke about what he can do with a welding laser.

Repeatedly in the story, you spend your time getting Joey’s mind a new body, and that new body changes how Joey sees the world. The small body makes him frustrated and cautious, complaining a lot. The welder body makes him see the world in terms of how to wreck it. He’s frustrated by the weakness of his medical body, and when he finally gets a humanlike body, its complete alienation from his old life and the trauma of the change prompts an overwhelming personality shift. It’s really fucking traumatic when you think about it, when he literally ditches his name because it doesn’t fit his body any more.

And then, at the end, you find that Joey is the metaphor of the setting: the city is Linc’s body and Foster is crawling around inside it, trying to find the ways it works even as it tries to make Foster part of how it works.

This game is about being digested by a city that can think and feel and it fucking hates you.

In Beneath A Steel Sky, the character is not made aware of their destiny, their potential, until the moment of deciding whether or not to accept it. This is important to me for two reasons. First, it means that Destiny isn’t an immaterial force that exists in the world, surrounding our characters and driving them onwards. It’s not The Prophecy or The Force. Foster is important to the plans of LINC, and so LINC just tries to get Foster. The means are difficult because for all that LINC is connected to every goddamn thing in the world, the information available to a computer system is not the same thing as the information coherent to a computer system. Foster is able to literally walk around inside LINC and not be recognised, because LINC doesn’t know what it’s looking for.

It can find Foster by signifiers; it can give orders to human interpreters, and those human interpreters can try to find Foster, and indeed, one does, and when that human misunderstands the command, LINC’s only real option is to murder someone to death, with its very limited toolset.

That means you do get the linear path of a ‘destined one’ narrative, where a character is Important To The Plot for reasons they don’t understand and never chose, which we can all love, but you don’t need the whole cosmology of the universe to be bent around it. Foster gets this kind of attention and treatment because it’s relevant to the villain’s plot.

The other thing is, Foster doesn’t get told in the first like, third of the story, hey, hi, you’re the Destined One and now all your actions and decisions are going to relate to that and you’re going to have to make a choice to pick up your destiny like you see in other Destined One Narratives. The majority of the story in those Destined One Narratives use the Destiny to focus on the one character and as a sort of all-purpose explainer for why a character might be treated as important by people who have no reason to know anything about who they are, how they choose to be, or what they choose to do. Instead, the whole story builds up to the discovery of the Destiny and one single choice.

Also, I like that the correct choice is to not become a computer’s meat puppet dongle, and instead you take a computer that learned the wrong lessons about how people behave and filter that through a caregiver who can see the way that proper distribution of resources for the betterment of everyone can fix things.

It’s a lot like a Conspiracy of a Destiny.

One of the weirdest things to me about Beneath A Steel Sky is that I’ve always had it on the backburner as a thing to cover on the blog whenever I have a free empty slot and I’m too tired to go deep on something, because the game is etched into my brain, extremely easy to recall, and free, so I figured I wouldn’t really have much to say about it.

Turns out uh, no, I really like this game, and I like it in ways that sort of unfold as I think about it. Originally I just wanted to position it as ‘the good one’ compared to The Dig, which is still a game I like and think works really well telling its high concept science fiction story and it just so happens it was made in part by a complete dickhead.

Thing is, Beneath a Steel Sky wasn’t made by Someone Legitimising It. It was made by Revolution Software, with names like Charles Cecil, Daniel Marchant and Dave Cummins, and it was made with David Gibbons, one of many hands together, on a system that has now slowly melted away in our history, such that when Dave Cummins died not even Charles Cecil knew about it for years.

Beneath a Steel Sky is a game made by people and it legitimises itself.

1 Trackback