Alright, look.

This game, Axiom Verge, is a Metroidvania. Do you know what that term means? Do you know that term in a way that makes you use it instead of the term ‘exploration platformer?’ Okay, cool, good. If you don’t, there’s this great genre of interesting platform games and I’ve covered a few of them in the past; particularly, I really like Shantae, if you can handle a game that’s pretty horny and Cave Story, if you can handle a game that’s pretty hard.

I’m not saying that Axiom Verge is a bad game by bringing up these other, more approachable games. Axiom Verge is really pretty damn good. But as a game it feels to me that you probably need to have experience playing a Metroid game specifically to get your head around the way this game handles its spaces, enemies and resources. You want to know how videogames can glitch, about how things can fail in a way that games largely don’t do any more, except when it’s done deliberately. And you want to know how big a world can be, how to remember seeing things you can’t quite make work yet. It’s not even assumed knowledge – it’s just that Axiom Verge builds in a genre like few games I’ve ever played.

Axiom Verge is, as a game, a game for people who like Metroid games, and I feel like it’s pitched at the kind of player who can appreciate what this game does differently. It feels like a game that wants literacy in what it’s doing, because it can’t explain itself to you the same way other games in the genre do.

So, there’s your Videogame Review spiel. Axiom Verge is a videogame/10, I’ve mentioned Super Metroid and maybe implied that the game has enemies and resources and such. You can go buy it here, if you want to.

Okay?

Now then.

Spoilers ahead.

When I write about games I try to make sure I write about the things that the game is trying to do, or ideas the game presents, or an interesting story that you can hang on to about the way the game makes you feel or teaches you things. I feel like my primary audience is people interested not so much in whether or not to buy games but who are very interested in what games do and how they do them to us.

In Axiom Verge, the thing it does is two things,

and they’re the same thing

and you might not have noticed.

The story of Axiom Verge is about time, and what it can do to people.

I’ll explain with one example. The example of the first Rusalka you meet, Elsenova. From your perspective as a player, it’s pretty basic stuff, extremely Videogames. Your character, Trace, the person you play, comes into the story at a sensible point to him; he has an accident, then he wakes up in a strange, alien location and gets a weapon that lets him fight baddies. That’s some typical adventure stuff.

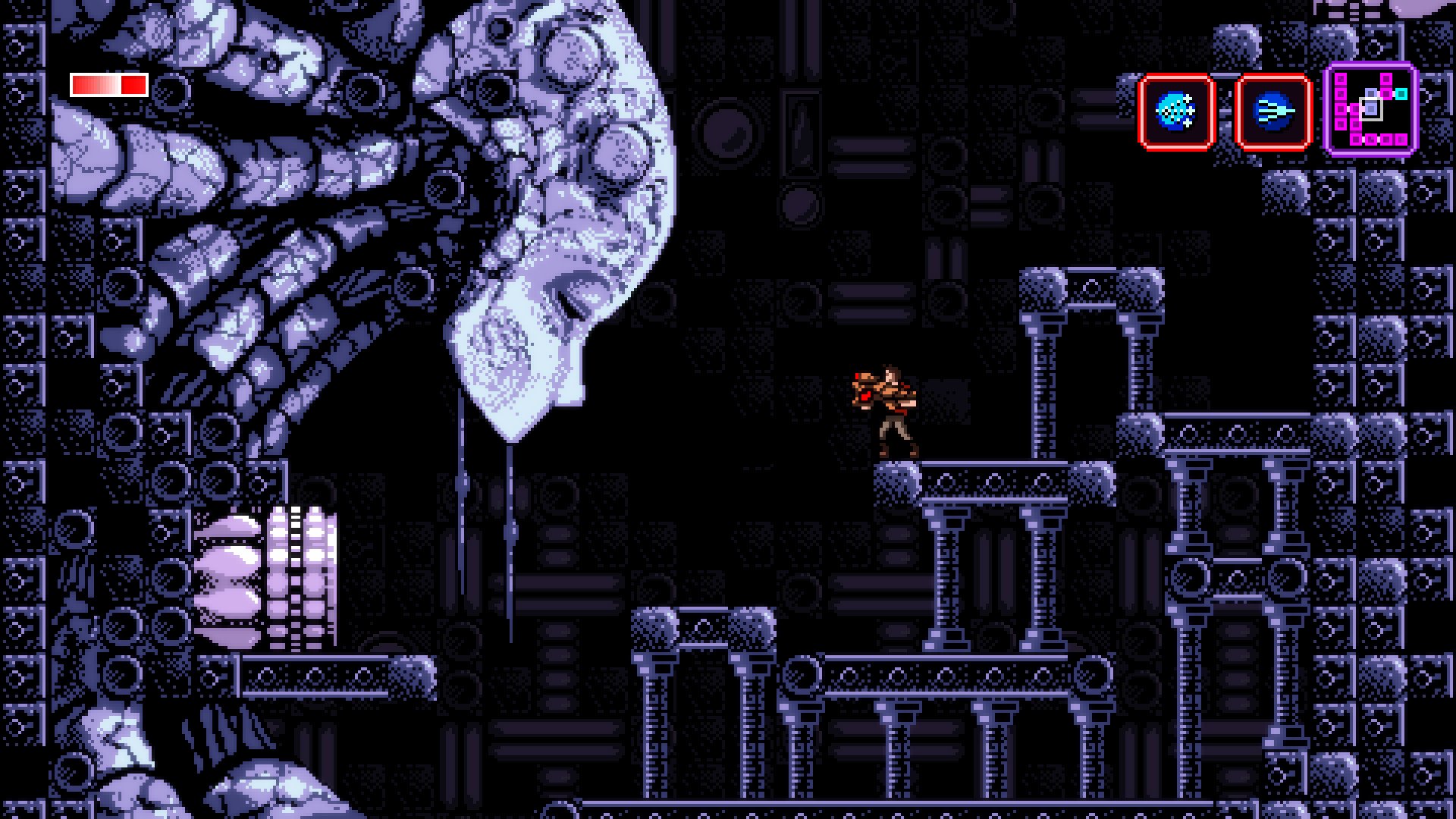

Then your first major destination, a destination that is pretty much all you can reach, is a door, through which you find a dead end room, and encounter there a giant crumbling lady head, you know, one of your typical giant crumbling lady heads. She introduces herself, explains she’s the voice in your head, and she starts giving you partial information about where you are, what’s going on.

If you pay attention to the world around you, Axiom Verge has a very detailed level design but it’s in these peaceful places the tilesets ask questions. This place tells you through its architecture, is that whatever purpose or reason it had for the details you can see, it no longer has that purpose, no longer that detail. Was this arch taller than the others because it originally held something underneath it? Why is the background darkened here? The surface of the woman’s head is smooth at one point, but cracked and damaged in others, what happened?

When you see this character for the first time, you might perceive her jawline as complete, her face like an infant sleeping. She is young, perhaps her simple speech is a byproduct of being a child. A huge, powerful robot entity but one that you can understand, a little. She doesn’t know what’s going on. You don’t know what’s going on. She seeks help. She offers help. You can do this. You meet her sisters, you learn of the history of this world, you learn of the scale of these creatures. Through it all, this stilting-voice young creature guides you.

Then at one point she kills you while she’s mad.

You get better, but it recontextualises everything.

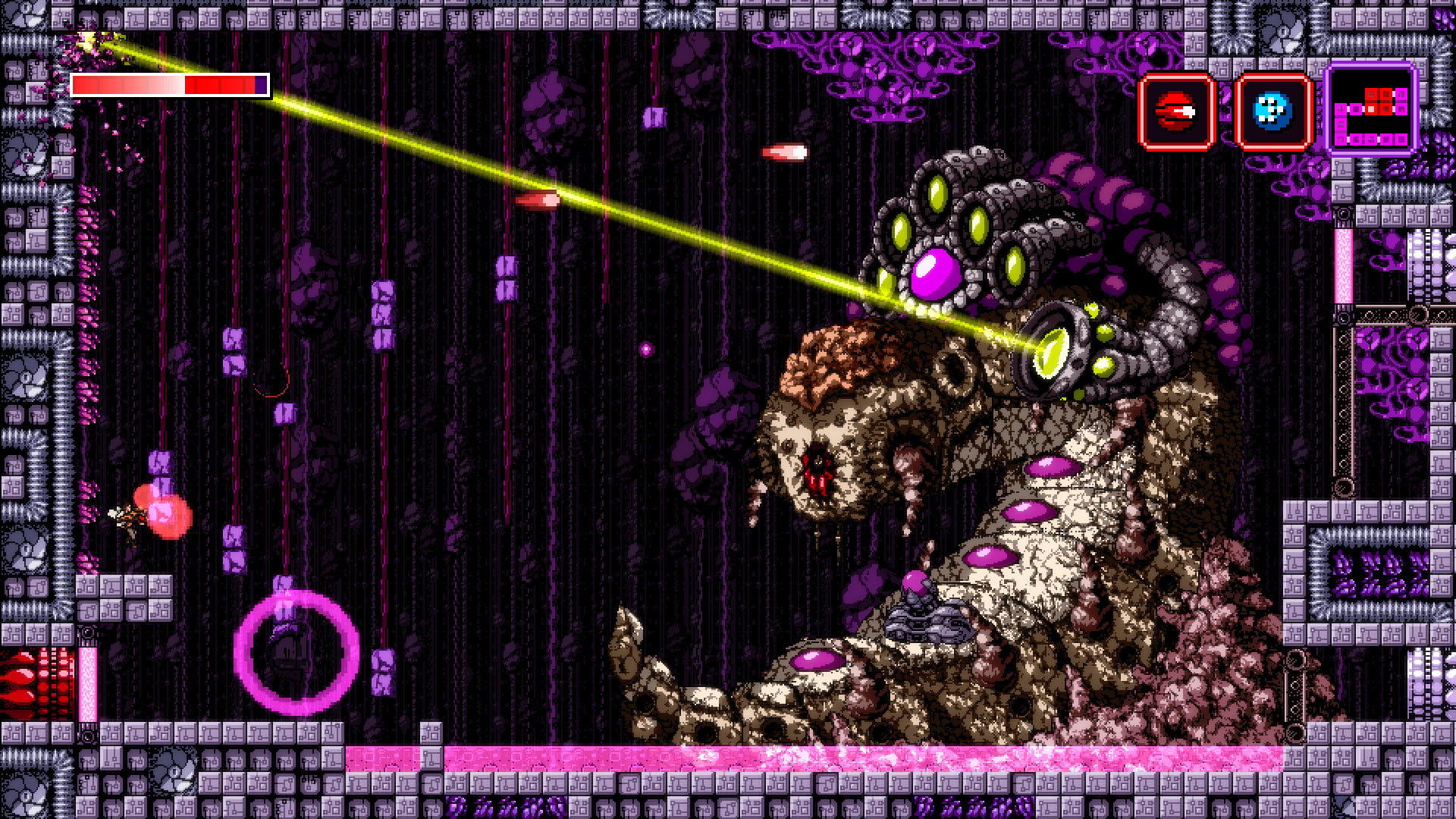

Look at that image again.

Her head is not whole. Her jaw has been torn off; the eye you can see is barely open, and narrowed as if angry. The whole disposition is threatening when you fill in that detail and knowing this plays into what you later discover about this character, this story. At first what seems a sleeping innocent, you learn as you piece together the story of this world that you have met a maimed woman who barely contains her rage.

Axiom Verge’s story covers centuries, not just in backstory, but from the first moment of the game, the establishing cutscene, to the end of the story you play out is a few centuries. The backstory before this point is centuries more, millenia.

Axiom Verge’s story covers centuries, not just in backstory, but from the first moment of the game, the establishing cutscene, to the end of the story you play out is a few centuries. The backstory before this point is centuries more, millenia.

You learn about a culture powerful enough to create super-technology that spans universe, as it slowly transitioned from a supertechnological scientific culture to a religious one that deliberately did not understand the devices they had. This world had Rusalki swimming in the sky – up above the atmosphere, yet still so large they could be seen from the ground, and were grounded by the actions of a high priestess who feared the outside, an outside her very people had found a way to reach.

You learn about the confinement on the earth and beneath it that these Rusalki chafe against so slowly that immortal beings learn how to become mad. They develop in-fighting, they create murder, all things they had no reason to develop until they were confined by so much time.

You learn about yourself. You learn about how you are a memory of the person you started as, a fork point looping back. You get to look at yourself after five hundred years of time has passed, where you, the person who was afraid of killing anything, became a genocidal monster. You see all the clones of himself he made and turned into monsters, again, over time. Athetos killed a world in the name of saving his own, and his final hope to escape Sudra was to let time kill the Rusalki so he could leave.

Time changes people.

You learn things, things mean different things. The longer you have, the more you wonder about what lasts. About what matters.

And Axiom Verge does this to you, the player, in its short duration. The image of Elsenova presented to you at first is very different to the image at the end, and all because you’re taking too much time.

I think it’s telling that one of the final things Axiom Verge offers you acknowledging you don’t have a satisfying ending, from Trace’s perspective.