Ace Attorney Investigations is a 2011 Nintendo DS game, best described as a Narrative Adventure game. See? I told you I needed it. Building on the success of previous Ace Attorney games, Investigations gives you space to wander around, all floppy-cravat style, and Investigate, as an Attorney would, or as you might imagine one would, if you had a very active and extremely silly imagination.

If you’re not familiar with Ace Attorney franchise games the basic gist is that you’re playing a lawyer in a legal system that is both completely ridiculous and yet, harrowingly true-to-life for actual Japanese legal proceedings. Prosecution in the Ace Attorney universe is phenomenally powerful and convictions are almost guaranteed. In most of the stories, you’re cast as a defense attorney dealing with prosecutors that are some variety of Training Wheels, Cyborg, BDSM mistress, Boy Band, Last Blade Assist Trophy, Cowboy, Noble Mom, Your Boyfriend and Hellbeast Double Murderer Jailmenow.

These prosecutors have all the power in the courtroom and you’re assumed guilty, no matter what the situation. If you run the Judge out of patience, Jail. If you don’t correctly present the right evidence at the right point, Jail. If you present the right evidence at the wrong point, double Jail! It’s something of a joke how many times you can provide reasonable doubt in a case and it won’t matter because the court requires overwhelming definitive proof.

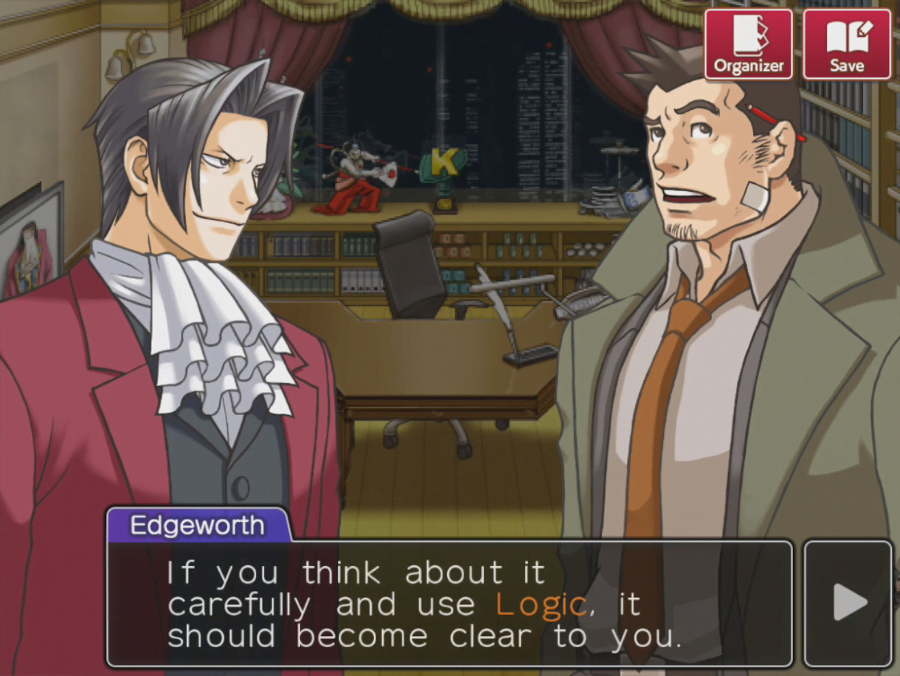

In Ace Attorney Investigations the upper hand is on the other foot, and you play Your Boyfriend aka Miles Edgeworth aka The Frillnecked Wizard, as an instigating incident of a stranger shooting something in his office (a person) kicks off a plot of a conspiracy, a crime, and international incidents involving diplomatic immunity and air crimes designed to contain that prodigious authority and power that the other games make clear that Prosecutors have.

It’s kind of funny actually, you have to do so much to get an absolutely perfect airtight case against the murderers in Investigations that it’s no wonder the prosecutors in the rest of the Ace Attorney games go into court convinced they’re 100% right. These murderers have literal howling breakdowns when they rant and confess and sometimes undergo actual physical transformations. It certainly would shape your position.

Okay, so this game is about playing a weirdo lawyer in a weirdo law-world striving for the truth in a whole bunch of pretty weird murders. Why is this so special?

Well I guess the first thing is, I think this game is really fun. I love it, it makes me laugh and it has characters in it I like. Narrative Adventures often feature memorable characters and dialogue, and this one connects me to characters I already knew and characters I’d never met.

It also doesn’t push on its puzzles too hard. You don’t often run around with a long list of various bits and pieces in your pocket hoping to rub them against the notches in the world around you where they fit. Instead, puzzles are much more about being presented with a question and then showing which of your items relate to it. There are some tile puzzles and some find-the-detail puzzles, but they’re not meant to be obtuse or weird, they’re just trying to represent your character engaging with the evidence in front of him.

Still, there’s also some great ideas in here for when you make your own Narrative Adventure games. Particularly the way this game uses space and time. See, one thing that most of these Narrative Adventure games had as a big problem was a difficulty of conveyance. Conveyance is a topic I’ve talked about before, but in basic, Conveyance is the way a game encourages you to keep playing it. You might have heard this called ‘Play Conditioning,’ and imagine me saying that through extremely grit teeth.

Narrative Adventures are infamous for having awful points when you’re brickwalled by not knowing exactly what to do. Sometimes this is what we call ‘Dead Man Walking,’ where you’ve made progress impossible by some earlier action that you can’t undo. Sometimes it’s because of finding a specific object that’s deliberately hard to find, known as ‘Pixel Hunting.’ Sometimes, it’s because the puzzle is needlessly incomprehensible because you can’t connect to the idea of the creator in that fiction. These are all problems you can fix by just designing around them, but even without those specific problems, you’re still going to find there are times when players don’t have a way to go forward and don’t know what to do.

The problem, basically, is that you know you need to do something, you may even know what that needs to be, but you don’t know how to do it. In most of those Narrative Adventure games your interface lets you look at the whole world, and creates the illusion you need to interact with all of it. In Ace Attorney Investigations you’re instead looking at this smaller space. Smaller inventories. You have fewer ways to interact with anything – because you only have a few buttons that the game can even let you press. It’s a really tight game. This tightness, this narrowness, lets the game keep you from being overwhelmed with possible places to push the story forwards. You’ll still get stuck, but there’s a lot less aimless rubbing of objects against one another to get unstuck.

Yet when we talk about Narrative Adventure games – usually by some other name – we often leave the Ace Attorney games out. I know people who love Narrative Adventure games who’ve never played one of these histrionic, silly games. The demand for Investigations was low enough that even though Capcom have made a sequel, it’s never been distributed in the west.

I harp on history of videogames because it’s one of the ways we need to learn about ourselves. There are all sorts of big-seeming questions, questions about culture as a whole, that are all malformed because we haven’t really been paying attention. Questions like ‘are games art’ and ‘do trans people belong in gaming’ and indeed, ‘why did the point-and-click adventure game die.’

Videogame history is a mangled, half-remembered mess of the common consciousness that is mostly defined by marketing and brands. When you look into the history of these things, you’ll see amazing things, like how there’s a line of creative work that draws directly from the unassuming timed puzzler videogame Lemmings to the real-time horse-ball shrinkage engine Red Dead Redemption 2.

Inasmuch as paperwork is concerned those two games were made by the same companies, even if in a weird, Ship Of Theseus style way there’s really nothing in common between the two points in history. There was a point in time when unassuming little DMA Design of Dundee Scotland shaved the side of its head, bought a bunch of leather jackets and insisted you start calling it Rockstar like some kind of unutterable superdouche.

I was in a Journalism class a in 2013, just before Grand Theft Auto 5 launched. The game came up, and I and another student had a bit of a go-around about it. That student was extremely defensive of criticism of the game – a game that neither of us had played, mind you – when I pointed out themes and ideas the game was advocating for being tired, boring and making interesting things into hacky jokes. His rejoinder to that was the series had always been like this.

He’d been born in 1995 and been four years old when Grand Theft Auto was a top down plotless, unvoiced sandbox game. His personal experience was Grand Theft Auto 4 being a lot of fun when he was in high school, and therefore, Grand Theft Auto 5 was going to continue a glorious legacy that he was pretty sure was exactly the same way he remembered it being for the whole of his life. To him, there was no Grand Theft Auto 1. There was no Lemmings.

Videogames, as a historical entity, are a space where almost nobody does the readings.

In that interest of historical information, of putting these games in context – and overdoing it, really, I mean we’re three and a half thousand words and counting if we include the Narrative Adventure article at this point – I should disclose something more. See, I love this game, and I used an FAQ to play it.

We are extremely down on the idea of doing things to make games easier. I’d love to feign ignorance and say something ‘I don’t know where this idea came from,’ but I do know where the idea came from and it’s the idea that’s always been there in games. It’s the idea that we need to find some way to look down on people. It’s odious and it’s gatekeeping and it’s also boring.

I want to hand this game to my friends. I want them to be able to enjoy it, and I want them to be able to get through it. I want the puzzles to make sense, and I want people to know where to go next when the game’s conveyance has failed them. Because the fact that I did get through some of these games unaided doesn’t change the fact that I don’t always get to. This is a game where even a confident player is going to have to make some guesses not about what the problem is, but how to communicate that problem to the game. And when they do make those guesses and work things out, and we talk about it later, it’s going to matter to me much more that they were not so frustrated the joke on the far side of a puzzle fell flat than that they somehow ‘built character’ by dealing with a thing that was boring and annoying the way our Gaming Masters intended.

Now, one last detail: I have some very good news about Ace Attorney Investigations. When I first drafted this article, I did it thinking that there was no option for playing this game except to buy a Nintendo DS and the cart, which effectively put the barrier for entry for this game around sixty dollars.

I have learned in the making of this piece that Capcom, released this game on both the iOS and Google Play stores, without much fanfare at all. These versions of the game are made with the same unscaled pixel art for most of the game, but the conversation sequences are done with high-res versions of the original game artwork. That’s where I got the screenshots used for this article, and that’s why they’re so nice and crisp.