During July 2017 I went on what I can only really think of a bit of a bender working on games. Specifically I was working on games pretty much constantly for a few weeks there, and as a byproduct, made five titles in about three weeks.

You’ve heard hype about some of them. Sector 86, the little push-your-luck blackjack-a-like that I played a bunch of times. Good Cop, Bear Cop. Pushpins. There were quite a few titles that I tried out and shared on Twitter. Some of them became proper, full blown game releases, games I happily play now with my family and advocate for you to buy, with money.

One of these games was Ruck. Ruck is a game I want to tell you about because Ruck didn’t work. And then, when I changed Ruck into something else, that something else didn’t work. And now, as I finalise the last touches on what Ruck became, I wanted to show a very, very basic explanation for how Ruck was a failure.

First things first, the basics of Ruck.

Ruck had an aesthetic, didn’t it? Man, I like how this game looks. This is a style I’m reluctant to release under now, because it turns out that celtic knots? Kind of popular with Nazis, who seem to think they’re all secretly vikings, even though they don’t know what vikings are.

Ruck cards operated on three basic parts. They had a strength and a suit; the strength is the number in the corner and the number of shields in the center. The suit is the symbol next to the number. And they had a value, which was their dice value. You played Ruck by arranging hands of your soldiers against your opponent’s soldiers, then both of you rolled dice, ala Risk, to see who won. You rolled dice by flipping cards off the top of your deck to the right number, and then put those cards on the bottom.

The design was kinda novel. I liked that your hand of open cards, the army you were sending, showed the numbers they couldn’t roll when the time came to roll dice combat. I liked that there was a good-better-best system of dealing with each others’ cards. I liked that the whole thing, mathematically, proceded very simply, giving you 6 (dice faces) * 3 (suits) * 3 (strength) = 54 cards, the same as in a normal deck of playing cards. It was very nice.

Problem was it was both boring and random.

When you put your army forward, you didn’t really know what it was going to face, and you didn’t really know how well you’d do. It had almost the randomness of dice math, but without the ease of just entrusting yourself to the dice, and without the tangible satisfaction of the dice as an object.

The cards being all the same, visually, plays well as making them aesthetically pleasant but it doesn’t make them good mechanical objects. You’re not going to be sure what the cards do at a glance. Maybe as a sub-system this aesthetic could work, but as the whole game it’s very dull.

The other thing about this is that I do think the ‘resolution via card value’ is a really good idea. Another game – ideally one that’s a builder game – will let you flip cards to reveal powers or values on your cards (cards that have another purpose), which means you can design cards that are both very good to play, and very bad to flip, with some interesting tension there.

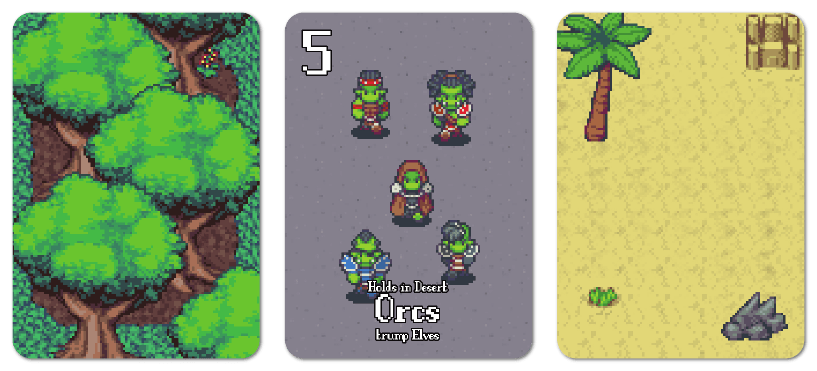

This design gave way to a simplified look when I bought some pixel assets:

Next came this version, The Domains of Meh. This game had an identity though. Originally it was going to be kinda a JRPG war game, with mechanics for each unit, and you played the game for a battlefield made up of the backs of your cards. When I made the cards though, none of the units looked like they wanted to fight, which gave me the idea for an empire at war where nobody was very committed – so you didn’t fight, you just went home if you could see your army was outsized. This then created Meh, an empire of extremely gentle and soft people who would Rather Not, Thanks.

This time, the game worked fine, but it was also mismatched. The game had a few flavour problems – why do orcs trump elves, why do they hold deserts, which takes precedent, a trump or a hold. Also, it was just, in the same way, dull. The art was really bursting with personality – why should the armies you play be so dull? so, another, final revision.

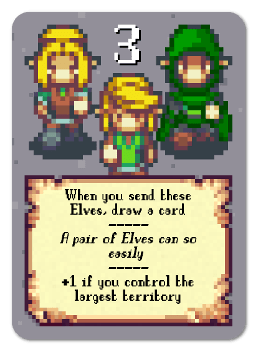

Where we’re at now is with a game which is a little smaller. It’s tighter. You only play 9 cards but the game is now about area and territory control, and armies have special abilities that make their decisions different.

Here’s where it ended up.

You don’t see most of my mistakes. Most of my real failures. They don’t get shown off, I’m usually pretty good at only sharing things I really think I have an edge on, and when something breaks I can still see ways to make it good. Sometimes I ask about an idea to see who’s interested in it, and see if it’s worth pursuing.

I want you to see this failure that took me a year to fix, because I don’t want you to think I don’t try and fail and have to try again.