It is easy perhaps to forget that TTRPGs are a fundamentally creative space. In some games, especially the more modern indie style of TTRPG, characters are often handed a role that really paints the way they should feel, a characterisation that is in some cases extremely specific, like you’ll see in PBTA games. In D&D, there’s a lot of ways in recent days that flavour has swung towards specificity, which can limit the kinds of creativity you can express.

4e D&D is a game system that deliberately tries to leave a lot of your flavour up to you. Last year I talked about some character options that let you be horrifying heroes. This year, we’re going to do that again, but instead of gothic horror, we’re going to look at ways to do cosmic horror with your character that swings a big axe and saves the day.

Cosmic horror in this case refers to the horror felt at the boundaries between human agency and universal indifference. Cosmic horror can be felt in a very mundane, normal moment of life when you look up at the sky and realise that there is more that exists that you’ll never see, that the universe is old in a scale that you will never understand and will live on longer than you will ever be able to conceive, and that these two details make you a nothing of a blip between nothing blips. When we talk about cosmic horror as she is shown in media, it’s often about trying to show you those points of interface: Of the horror that Lovecraft himself said,

“Now all my tales are based on the fundamental premise that common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.”

The horror of the Cosmic is not the threat of Gothic horror. It is the immense indifference of an uncaring, infinite emptiness.

Warlock

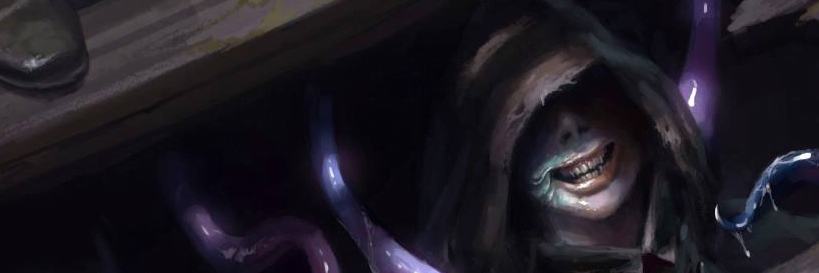

First port of call, first and finest and easiest. The Warlock gets a pact out of the box called the Star Pact, where you’re connecting yourself not to demonic forces on our world, but rather, in tune with things from beyond the stars. There are things out there, things that are vast, and distant, and somehow they can be brought to bear, a tiny drop at a time, here. You’re not letting people taste the power of the Far Realms, you’re showing them a shadow of it, and their seeing it is enough to rip at their reality.

If you take to this path, understand that your immediate reaction to other Warlocks is going to be disdain. They work with Demons, things that live and die in the lifetimes of cities; things that come to the earth and can be slain, things that need human agents, things that care.

The Star Pact Warlock probably isn’t really communing with the things beyond. They’re probably not even really understanding it – they’re just finding a way to coalesce some stuff from outside, and the mere effect of it is rotting to the brain and soul. You’re a nuclear physicist surrounded by people running steam trains, and for you, the problem is not how much power to use but rather how much power are you capable of surviving releasing into the world.

You’re not superstitious, you’re careful. Your rituals may have a number of things that you don’t think are necessary, but you’re keenly aware that diminishing the importance of any one part of it runs the risk of breaking the whole thing. You deal in tolerances, not contracts. What you work with runs the risk of spilling over, not out of malevolance, but out of complete and apathetic unawareness that there is any reason to not.

Skald

Stories have power, they say. The old stories, have the oldest power. They talk about a time before there were people, talk about a time in the deep oceans and the old snows, they talk about mountains that move as people. They talk about the bones of the earth. The stories of the world that don’t need or care about anything that people do, because the stories

are older

than people.

The Skald is a storyteller of violence, someone who knows the power of names and rites and rules, but who doesn’t necessarily know where the stories come from. There are things in the ice, up in the stranded colds where the word skald comes from. There are things that landed, long ago, and have done nothing but dream, contained under the cold, as it slowly creeps across the land. They say that there are things out in the ice, things in the frozen weight of oceans, that can drive a person mad.

And there are things that say they already have.

If you take this route with a Skald, you’re going to want to brush up on your Lovecraftian horror phrasing. Cut your stories short, hold up a finger, and tell people that’s all they need to know. Find unsettling old epithets to use, or ban yourself from wielding certain words at certain times. Your people survived in a place where nobody can, and they did so because of something that lurks, something that is, and something that does not care about you, but does respond to you. Show respect, and you can exist in its swirling eddies, and the flurries of forgotten drifts.

Fighter

What? Really?

Yeah, really. By default, it’s not hard to be a fighter with Lovecraftian themes, because almost iconically, one of the oldest examples we use for the fantasy setting fighter was Lovecraftian. Conan the Barbarian existed in a Lovecraftian setting, surrounded by many of the things that were from Lovecraft’s horror stories, and his response to that?

Well: Can it bleed?

The Lovecraftian fighter is aware. That’s the thing that sets them apart from most of the characters in these spaces. It’s not that they don’t know that there are horrors beyond imagining – it’s that they’re worn and in many cases, practical enough to recognise the things they can’t do. They can’t preserve forever. They can, however, fight for right now.

If you go this route with a fighter, I’m going to recommend that your character invest in things that make their will save stronger and lots of different devices and items – even expendibles – that make you capable of taking extra saving throws. It’s important if you’re going to play a fighter who’s been touched by the outside and is soldiering on anyway, that you do so by showing someone for whom lesser horrors are extremely passe.

Paladin

Why is it the first words an Angel says, in the Bible, are so often something like fear not?

It’s because Angels are fucking terrifying.

Now, personally, I don’t go trucking with any absolute-morality-having holy-being magical construct critters like Outsiders as being actual arbiters of what is or isn’t good or bad, but they’re a good avenue for something that’s meant to be of an inhuman vision of morality. Your Paladin may not deal with flitting angels and sweet thrones or hallowed human avatars and prophecies, but may instead be a gateway, a threshold, for things that have been created, coalesced, and collapsed together from human expectation.

Imagine if centuries of a church’s existence has resulted in a thing that’s like a god, a thing that they may well name the thing they believe in, which isn’t so much a sentient, coherent god but is more a sort of accreted wellspring of hopes – hopes that can be misdirected and misunderstood. Imagine the strange, clamorous shapes that may take as it strives to fulfill the visions of thousands of worshippers, over many years. It doesn’t know what it wants, or what it should do, but it knows a simple, purified, extremely dangerous vision of holiness.

And you are the vessel that stands in the gateway between that power and the people around you.

An unnatural, inhuman vision of justice that it falls to you to ensure is actually just.

Druid

Did you know that Lovecraft’s own influences did not start in the sea or in space, but in the works of Arthur Machen, who penned the book The Great God Pan. In that book, the source of horror for the easily spooked meganerds that Lovecraft so loved as his protagonists was the discovery that the woman he’d married was really the avatar of the thing that, in Ancient Greece, was known as the god Pan – and that ‘pan’ was not just a word for a god’s name, but also was the Greek term for everything.

The origin point of the Greek God Dionysus is also a similar thing, where Dionysus is probably older than the Greek Gods that we consider ‘the normal ones,’ as a sort of strange cult of nature and madness and dreams, because back in the day, wine was seen as letting an actual spirit possess your body and do weird things.

The cosmic horror does live in the woods, too; out in the spaces that are so close, so adjacent to humankind’s decisions, but still completely apathetic to it. You can be the smartest person in the world, but it won’t let you outwit a bear; a bear just has a fundamentally different way of looking at the world, a different set of senses and perceptions, and it doesn’t need to be smart to threaten you.

A druid of this kind also has another toy in the toolbox; the way that the powers of a druid are deliberately vague about the kind of things you can turn into when you go into Beast Form. It even specifies that you can choose the way you look – so, in this case? Take on the form of something… wrong. Something that is definitely not the type of thing people mean when they mean ‘a beast.’ Something made out of writhing tendrils, or gathering leaves, or a shadow cut out of suspicious darkness with all sorts of eyes inside watching you.