Content warning: I can’t help myself from bringing up the Nazis.

I’m not joking.

This month for 3.5 content, I went to the library shelf and yanked out a book of the type I hadn’t looked at much – Secrets of Xen’Drik, a setting book from the Eberron campaign setting. Xen’drik is the southern continent of the world of Eberron, and the largest body there, a sort of ‘global south,’ if you will. It’s covered in jungles, and the ruined remains of the earliest civilisations that defined life on the planet, which are still populated by a xenophobic, murderous and untrustworthy population of dark-skinned culture of people who used to be slaves.

You know when I say it aloud like that, that’s kinda yikesy.

These particular types of book are a sort of fun vertical slice of content for 3.5 D&D. The book is broken into four basic chunks – there’s a section of world information, designed to give people an idea of what’s in these areas, what you might know about if you’re from there, or just to set the tone of the world it’s part of. This includes a lot of stuff that’s technically rules information – it’s like how you map and navigate this continent or the cost of travel to and from the locations, or inns and the like. It’s not unreasonable for players to have that mechanical information. Then, there’s sections on components of adventures in this section of the world, like a sort of lite Monster Manual and traps and poisons guide, and a bit of political stuff, and then there’s a section that does present this content as a type of mini-module. Rounding the book out, there’s a ‘player’ section that gives you prestige classes, feats, equipment, and all that sort of stuff that players tend to want to comb through books for, with the idea that these represent the kinds of disciplines or skills this place enables.

It’s a solid book!

Special mention to the Primal Scholar prestige class, by the way. Remember our friend the Fochlucan Lyrist? Well, the Primal Scholar can be a bridge into that class, because it gets Bardic Knowledge. But also, the Primal Scholar hits our pissing contest between the sorcerer and wizard, where the Primal Scholar gets special perks, based on intelligence, that make you capable of casting spells spontaneously, and one of its perks isn’t even usable if you don’t use a spellbook.

Fuck you, sorcerer.

Anyway.

The book is perfectly solid as they go.

Anyway, let’s talk about the stuff in this book that means we get a content warning.

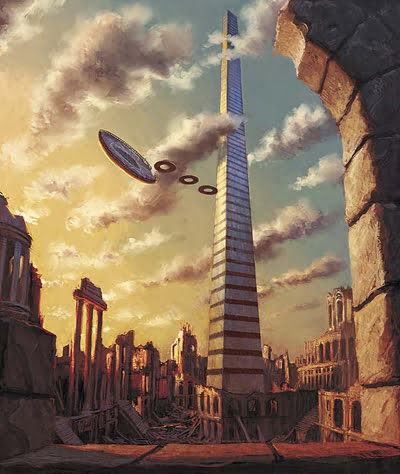

Xen’drik is a continent where there was an empire of Giants. Giants from the before times, Giants who built amazing buildings and powerful structures and an empire that spanned the continent and no further. The scope of time of the Giants’ empire is … kind of jawdropping. The book says that the giants ruled Xen’drik for 80,000 years, whereupon they were overthrown by their slaves, the Drow.

The drow.

Phew.

Okay, let’s face it: Drow are one of those parts of D&D that reflects a lot of bad ideas. The matriarchal baby-eaters who dress like extremely uncomfortable lingerie models that populate the mainline continuity are already bad, but numerous attempts to ‘fix’ them result in making that entire idea space worse. In Eberron, rather than a matriarchal spider-cult society, they instead made them into, uh, a slave race living in the ruins of their owners’ culture, dangerous and hostile and still, you know, evil.

The story of the giants being overthrown does underscore that, you know, sure, they enslaved the drow for millenia, but the drow really did overdo it on their retaliatory revolution.

I mean.

I mean.

Anyway,

Palingenesis is one of those words you may not know unless you’ve been, for no particular reason, looking at a lot of documentaries that seek to give you a useful explanation of the roots and cultural form of fascism. It derives from a theological or philosophical idea, where the notion is about the recreation of a glory of the past, but is about the idea of rebirth, or reformation. It also shows up in eschatology a bit – Jesus basically uses the word to describe the ‘last judgment,’ a thing my people have used to ridiculous impact and to produce a truly shocking amount of extremely mediocre art.

In fascist studies, fascism can be simplified to a palingenetic ultranationalism – that is, a vision of nationalism that is so xenophobic as to see the only true future to be one about the return of the ingroup to a historical ideal. This is by the way, the root of all that ‘reject modernity, embrace tradition’ mindset stuff – it’s basically people parroting Nazi talking points, and often relies on cherry-picking examples from one period to contrast with another period.

The thing is, this palingenesis, the idea of a rebirth to an earlier glory, is a powerful one across most imperial nations. But to have that rebirth into ancient glory, you need, first, that ancient glory. That’s what Xen’drik is – a continent that was the seat of the ancient empire, and then fell apart, and is now populated by a dangerous other that lurks in those ruins, fighting over them as an entitlement.

Hell, they call the giants that live there now degenerated.

Xen’drik is a palingenetic continent.

The whole point of Xen’drik is to be that ancient glory, the ancient glory of a different time, a lost time. A time before the now, when you know, things were better, and more impressive, before things got worse. And there’s an implicit thought that follows there – that behold, an empire is a thing capable of making enormous, amazing, impressive things, things we cannot replicate, things whose lose is somehow even more tragic because it has led to the loss of the culture that created it.

In order to see the current, modern era as a tragic departure to something perfect, something greater that was taken from us by those people, you need to be able to point to history, to when things were better, and better in a way that lasted. And Xen’drik is the cradle of civilisation for Eberron, the place where it all started. It was an empire crafted by slavers that was overthrown by their own slaves, who now live as a shadow of what they had access to when they were slaves.

It’s this vision of Empires as kind of right. That an empire of slave keeping giants would make amazing great constructions that could last for millenia even without maintenance, rather than the real history and precedence we have where Empires hurt enormous numbers of people and resulted in the elevation of useless incompetents who don’t know anything about anything. The greatest achievements of the British empire may seem impressive, but they must be measured against the achievements of people who can never be seen because the Empire killed them for being in the wrong spot.

Empires are lossy, wasteful, destructive and breathtakingly incompetent.

None of this is to say that ‘Eberron is a Nazi Sympathiser setting,’ that’s silly. The point of it is to examine this idea, the assumptions that are part of it – things that we use as the stories that build up our reality, the worldbuilding we’re used to (and in many cases, which we respond to) are steeped in these ideas, these basic assumptions.