January 2019 Wrapup!

The ending of a month and the time to reflect on what was made in that month. How’s 2019 shaping up so far?

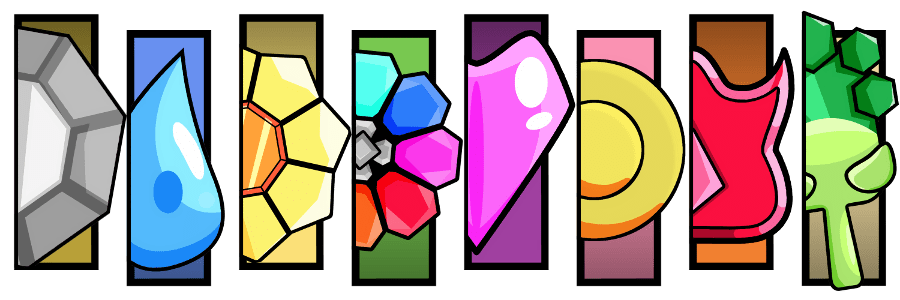

Continue Reading →January Shirt: On My Way to Victory Road!

Here’s this month’s t-shirt design!

Remember that feeling, when you were playing Pokemon Red or Pokemon Blue, when you realised you were collecting a lot of those badges, when you looped back around through Pallet town, when you realised that you had on you symbols, these signs of what you’d done, and now you were someone people could recognise as being achieved?

Here’s the design, on its own:

And here the design is on our friendly gormless supposedly unisex Redbubble model:

And here’s the design being modelled by the Teepublic ghost:

This design is available on a host of shirts and styles. If you like the look, I can see about making the individual badges into stickers.

You can get this design on Redbubble (assuming they don’t think I stole this artwork I drew) or on Teepublic.

Cancon 2019 – Aftermath!

Okay, that’s CanCon over!

The short story is we went to Cancon this weekend, and there, we sold games and bookmarks and postcards and other neat things and we stayed in a nice dorm with our friend, and we all had a Pretty Good Weekend and came home. We ate some pizza, we played some games, we talked to people and we had a bunch of fun. Then we came home.

Story Pile: Voltron Part IV: The End Of Voltron

Finally, here we are.

We’re going to talk spoilers, after the fold.

Continue Reading →A Good F**king Idea

For christmas last year, my sister got me a copy of F**k, the game. On the most surface level, this game isn’t one that interested me – it’s basically a party game, in that particular character of a game where you don’t have to pay much attention and it’s not super important how well you play. Plus, a plain white box with stark san-serif fonts always makes me think of Cards Against Humanity, a game I definitely don’t want. This meant I never really investigated F**k.

When I got the game, I did a quick investigation, and in a game designer way, it wasn’t actually very hard to put it together. The game is a stroop effect engine, and then includes a bit of spice in the form of Snap-like mechanics. You have cards you’re trying to get rid of, and getting rid of them involves not making mistakes – then the cards try to make you make mistakes.

I Like: Game Study Study Buddies

I travel around a lot, and that means a lot of my time I can’t read. Bus trips of 40-80 minutes are extremely difficult times because I have to conserve battery power on my phone while trying to not waste that time. If I had physical copies of books it might be a bit easier, but I don’t for most of them.

Enter Game Study Study Buddies, by Cameron Kunzelman and Michael Lutz. This podcast is a long-form treatment of academic game study books, and when I’m travelling it’s one of the things I can do that feels meaningfully productive for both easing me into a text or reconsidering one. They only do an episode a month, which is a bummer but it’s really interesting stuff if you’re interested in academic consideration of game studies.

The books they focus on are definitely biased towards videogame culture, except when they go back and do the Grand Olde Texts like Man, Play, Games. But that’s okay, because that’s what most of the people around me are interested in.

I like this podcast and I even sponsor it on Patreon. You might like it and want to check it out just for interest’s sake.

Game Pile: Oddworld: Abe’s Oddysee

Project: Hunter’s Dreams

The Pitch: It’s a 4th Edition D&D Setting/Modbook which is about playing Bloodborne and Castlevania style gothic horror hunters. Combat is not about crawling through dungeons and parselling out careful resources, but instead about short tactical fights of 2-3 sequences of fights in a row, known as Hunts, usually with solo-class enemies rather than larger groups.

Between each hunt, the players invest effort into the thing that forms the core of their group, their Nexus, determined by the type of group they are. You can build your own keep or workshop, or network of connected hunters, depending on the type of game you choose to play.

The aim would be to keep the tactical, movement-based miniatures-driven combat of 4th Edition D&D, and giving you a sort of ‘boss rush’ way of playing. DMs don’t need to design larger dungeons, but rather just small connected places for the hunt to find their prey, and thanks to the hunters being hunters, these encounters naturally can take the shape of kill-boxes, or containment points.

Details

This would be a gamebook, first and foremost; a single book that’s designed to work with Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition. Hypothetically, if your players are into other systems, it might be designed to handle that kind of cross-compatibility, but the basic point is to be a game system for a game I like. The game would then be made up of a series of modules that you snap together to make your campaign.

One module would be the rules for creating your Nexus. A Nexus sets some ground rules for the style of campaign you play in and also works against the ‘murderhobo’ problem that more free-moving campaigns have. A Nexus is something that roots you back to a space – things and people you can’t leave, and it’d have systems for checking on or recognising the nature of the location the Nexus is in. You’d decide at the start of the game if you want to control one of three options:

- A Keep. Your hunters are known and important, and they have to manage and marshall the resources of the town. They may rule the town, literally, and they go out and hunt to push back the boundaries of dark around the town. This is for your more basic ‘heroic fantasy’ feeling, and have a system for managing competing needs in the keep. Think of it as being an anti-dracula, or princesses defending their castle. People like princesses right.

- A Workshop. Your hunters are part of an organisation within a city, and they relate to the people who live and move in that city. They can be trusted or distrusted, liked or disliked, and the central establishment of the workshop means they can benefit from the connected resources of the city. Workshop games are more like your Bloodborne, where people might recognise that you are a hunter, not necessarily that that means they should respect you.

- A Secret. Your hunters don’t have any physical location that they centrally can meet at. They’re all people aware of a secret of the world, and that means in their city or town, they’re the ones who can understand what the monsters are here for. This is for your Buffyverse kind of hunters, though set in a more gothic horror setting. In this situation, inspecting the monsters and hunting them may be seen as foolish or dangerous. There may be no idea of ‘a hunter’ and part of the challenge of The Hunt is making sure you can gather your friends together in time.

One module would be about dealing with monsters and classifying them based on their grouping. Back in Ravenloft there was the mechanics of Fear, Horror and Madness, which kind of did a similar thing – in this case, the idea is that monsters represent types, and exposure to/interaction with a type can change how you react/treat them. This would be a space for ideas like beasthood or maybe insight from Bloodborne. If players want to contain the powers of the nightmares, this is where I’d put that kind of idea.

Another module would be for handling gear. The 4th ed weapon system is really good for things like transforming/trick weapons, or weapons that evolve naturally over time. Your Nexus might be able to replace a conventional gear system – with gear and abilities levelling up based on a budget/availability. One of the funny things with 4ed is that most gear was just meant to get replaced by level – you were never meant to plow your entire budget into a thing that you could hypothetically pay for, after all. Just making it so ‘downtime can be spent to upgrade gear’ seems an obvious way to streamline gear and reduce the quantity of knick-knacks that are a bit of a design problem.

Another module would be for ‘Races.’ Particularly, it might be useful to make a system for turning a lot of Races into Ancestries or Heritages, the idea that in this culture, what a Dwarf represents mechanically is just another type of human, and to put the races that are blatantly visually monstrous in a basket that let players play twisted, monstrous hunters. Imagine being a minotaur trying to hide in Yarnham.

Needs

Playtesting, for a start. It’s also a big project. Art for RPG books is always a thing. Fortunately, this is something I’m going to want to exist so I can run it, so that’s going to mean that even if it never gets made/polished and sold as a big project, this guide will still be useful as a reference point if I share development on this blog!

The Anticolonial Tiefling

With the recent rise of Freely Talking About Your D&D Character the internet has seen in what I’m going to assume is probably the fault of some extremely successful podcaster or whatever, I’ve been seeing a lot of talk about tieflings, and I want to present to you a take on tieflings I don’t see widely represented.

First things first: What’s a tiefling? It depends on the setting (as with all things), but the basics are that a tiefling is a type of human with a bit of demon blood. There are some creatures in most settings – most notably the Tannaruk and Fey’Ri in the Forgotten Realms that show that it’s specifically humans with a tinge of demonic blood in them. In some settings, the Tiefling are a bit like a rarity amongst humans – a Tiefling is born in a human line because a bit of the demonic influence in the family comes to the surface.

There’s often, in those settings, a similar type of creature that relates to celestial interference or elementals – the aasimar who bear a bit of the celestial, and the genasi with the elemental. And if you go down this rabbit hole you’ll find the Zenythri and the Chaond and all sorts of fun stuff, but Tieflings are the rockstars of this set. The Tieflings are the ones who you’ll often see alone, without the rest of the planar-cosmology-filling goofiness of the adjacent cultures. The Tiefling is almost obviously exciting, though. I mean, it’s a person with a demonic tinge to them, a little bit of the outsider, a little bit wild. It’s very appealing to an edgelord dork boy demographic, and certainly appealing to the monster-fucker genre of consumer, too. The tiefling, however, is also going to appeal to the fans of Hot Monsters as a voice of queerness, and that means you’re going to see a lot of people who are very happy to make leather-pants-wearing horned, tailed, spicy bisexual hot messes, and make their characters all about being a blatant metaphor for queerness. They’re a child born into a family that immediately recoils from them with horror, hides them away, and ostracizes them for their disruption of ‘the normal.’

The Tiefling is almost obviously exciting, though. I mean, it’s a person with a demonic tinge to them, a little bit of the outsider, a little bit wild. It’s very appealing to an edgelord dork boy demographic, and certainly appealing to the monster-fucker genre of consumer, too. The tiefling, however, is also going to appeal to the fans of Hot Monsters as a voice of queerness, and that means you’re going to see a lot of people who are very happy to make leather-pants-wearing horned, tailed, spicy bisexual hot messes, and make their characters all about being a blatant metaphor for queerness. They’re a child born into a family that immediately recoils from them with horror, hides them away, and ostracizes them for their disruption of ‘the normal.’

This is very basic queer coding, after all.

I personally don’t like it? Partly because the nature of queerness is that you don’t get born with queer horns on your head. Your queerness is a part of your identity that isn’t branded on you from birth and most importantly, being queer isn’t bad. A demon child that has actual special powers as an emblem of queerness really gets on my nerves because it kind of isolates the idea of queerness as both defined by birth (which it’s not) and monstrous (which it isn’t).

Every time I bring this up, though, it’s inevitable that someone will explain to me, helpfully, that queerness and monsters in media are often linked, and often queer people will identify with monstrous characters. This is very helpful because it’s definitely not something I’m already talking about and am already extremely well-aware of.

I’m not trying to take away your fun!

I just have my own preference.

I’d like to lead you to this other idea, though.

Tieflings have special abilities. They have stuff other cultures can’t do. Claws and fangs, and a feeling of fire, a tail, horns, sometimes unique feats, whispers from the beyond, a secret from a demon patron, a whole host of things. The tiefling is, mechanically, set apart from the human culture. As to why, well, there’s no real hard proof of where they came from.

Sometimes there’s stories of wars with planar invaders, sometimes it’s more that tieflings are byproducts of long-gone old sins. I like the 4th Edition D&D idea best, though. It presents the Tieflings as having been once the dominant culture in the world, with a super-powered magical empire that they then messed up so badly they not only cast a culture-wide sudo rm -rf / but also did it in a way that left every other culture very aware of what they did. They were humans who collaborated with demons and it changed them from being humans, and then, mixed in amongst human culture, there are these people, these tieflings, who have some of that ancient demonic heritage and powers just there, in them.

To this story, the Tieflings are the children of an empire that is no more and what defines their place in their current culture is that everyone around them is very aware of their relationship to that culture.

In this case, the Tiefling are both victims of empire, adrift colonists with no culture of their own, and beneficiaries, with all the old power that resides at their fingertips waiting for the tieflings to go get it… but that same power can be measured in terms of the peril it can cause the world. You may be saving the world, by turning these tools of global domination against themselves, but doing so comes at a cost.

This, this to me is interesting. It connects you to something monstrous, something big and something that you have every reason to resent as an individual. It draws the player’s relationship to their own potential power not as the invigorating power of gayness but of a question of how to deconstruct a master’s house.

That’s a question that often requires you to look for the master’s hammers.

TableTop AI: Dark Souls, Part 2

A few days ago, I thought about the puzzle of designing a Dark Souls like monster in a tabletop game. Rather than let that article sprawl long – because hey, card mockups are tall graphics – I figured I’d do some basic mockups and see what I could do with this idea of a monster with a deck-based AI.

Continue Reading →Story Pile: Voltron Part III: Best Beeves

Before I get to discussing the final season of Voltron and why it made me happy, I think it’s worth addressing that I don’t think this series is perfect. No series is perfect. In this specific case, there’s a bunch of stuff that annoys me, or things I’d rather they have done differently, moments where in this thirty hour long story, I would rather they have not. These are disagreements, they’re irritations – not quite at the level of a pet peeve, but bigger, and more specific, like a beef. I have beeves.

I try to make sure that my complaints about a series aren’t about what a series isn’t. I’ve talked about extrinsic vs intrinsic factors in television before. An extrinsic factor is things like ‘the budget was changed,’ or ‘this actor had to leave.’ An intrinsic factor is something like ‘this show chooses to be about men’s pain over women’s,’ (for example). And things like ‘this series wasn’t about the things I wanted it to be about’ are pretty extrinsic to me.

We’re going to talk spoilers, after the fold.

Continue Reading →TableTop AI: Dark Souls, Part 1

Okay, no preamble, let’s talk about making Dark Souls monsters in a board game.

I haven’t got the Dark Souls board game and I don’t think that having it would actually be illuminating. I’m not trying to find out how the makers of Dark Souls would do a thing, I want to find out how I would approach a problem of representation.

That out of the way, here’s a puzzle.

How would I make a Dark Souls Monster in a game I can make?

MGP – Confronting My Limits

Starting January 2016, I made a game or more a month for the whole year. I continued this until 2018, creating a corpus of 39 card or board games, including Looking For Group, Senpai Notice Me, and Dog Bear. Starting in 2019, I wanted to write about this experience, and advice I gained from doing it for you. Articles about the MGP are about that experience, the Monthly Game Project.

I’ve remarked, but not made explicitly clear, that the game-a-month plan had some problems. In the past I’ve talked about some general problems, like lead times and the awy the Pacific Ocean imposes itself between me and my goal of Making More Stuff. But rather than present that as my problem, I want to talk to you about your problem, if you want to try this same project.

There’s this idea in media making (and a lot of other places) that gets brought up called agility. Agility is the measure of how quickly or how well you can do… things. It’s often used as a shorthand for how quickly you can shift from doing one thing to doing another, different thing, or how quickly your thing can implement major changes. You might hear the term pivot get used.

I’ve remarked that making card games has a problem with prototyping. It’s just a mechanical concern; if you want to make a game like Magic: The Gathering, it’s not as simple as making a bunch of proxies; you kind of need some way to bulk create pieces to playtest with. Often that can make prototype printings, and that means that these games require a certain scale.

It’s very hard to get to that scale fast.

There are a bunch of games I’ve made that I couldn’t playtest at the scale, and I couldn’t prototype properly. Then, to hit the convention schedule, those games got rushed, and as a result, the games were… well, a bit weak. Just the truth of it: The games were a little worse than they should have been, which is a thing that I really regret now. Playtesting is hard, scope problems make it harder, and I flew real fast, real hard and sometimes it didn’t work.

That’s the problem: What’s the solution for you?

I have three suggestions.

- EMBRACE PRINT-AND-PLAY. Make your games for smaller spaces. Don’t think of bouquet card games, at least not for your first games. You can put a PDF out there in the world, made as simply as possible, which is just meant to give people a way to get the game pices working. You can do a lot with print-and-play – boards, sheets, cards, all that stuff. You might learn that ‘shuffling’ is hard, but you still get the basics of how a game works done. Players who make Print-and-Play are really good at knowing how much work they want to put in.

- BOOKLET SUPPLEMENTS. You’re one person, working small and experimenting with mechanics. Use existing systems and make single-page variants. Make booklet mods. Make a game that only needs to work for a little while, or maybe make a booklet mod for a board game – like I’ve joked about doing for Monopoly.

- MAKE THEM FREE. One of the games I’ve made that’s most successful in terms of distribution is Simon’s Schism. It’s also one of the games with the most feedback… and it’s also free. There’s a fear to missing out on sales for your free games, but you won’t make a lot of sales, and when you’re not charging people for your time, you don’t have to feel bad about making edits or updates to these games. This is your first period making games: Make a corpus of games that are more about showing people your work than it is about making money off them.

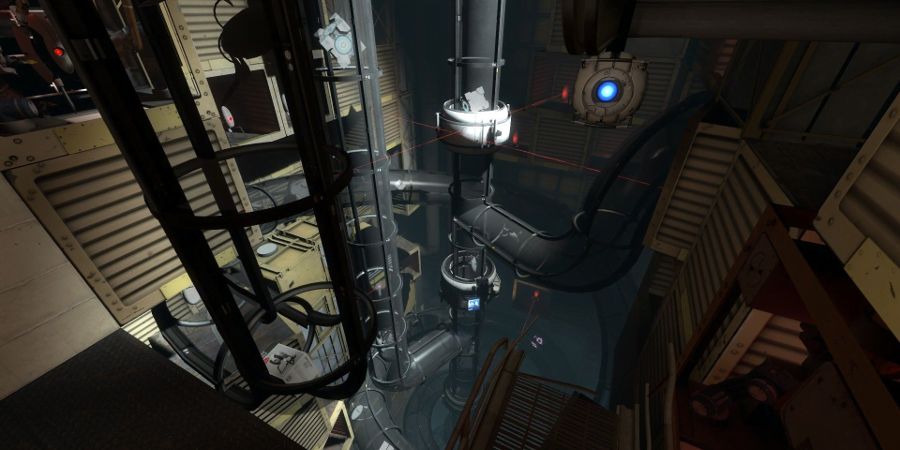

Game Pile: Portal 2

For anyone who doesn’t already know the vital statistics, Portal 2 is a first-person perspective puzzle game, the sequel to Portal, that was released in 2011, by People Valve Software Pays. Saying Valve Software made it is possibly overstating the role Valve Software, the organisation, has in things Valve does.

The game is centered around a non-speaking protagnist with a special tool that lets you create portals between two locations. It does this at range, so we call it a gun, because our brains and reference pool is pretty weird. These portals let you connect two points in space – and so much of the rest of the game is just built on exploring that idea. Puzzles become about how much freedom of movement you can get by folding two bits of reality together. It’s also fun because the human brain really isn’t built to deal with that kind of perceptual shift – it’s literally something our brains resist doing.

Filling in the rest of the space of the game is an evil AI that’s literally running you through the puzzles, as tests of your mental acumen, and the helpful AI that’s trying to keep you alive so you can escape. You’re followed not by bodies but by voices – old audio logs of a long-lost inventer, and the responses of your two AI companions. The game is stark and empty, but uses that emptiness to fill it with a dilapidated ending, and the story you get is made up of two fascinating parts: it tells you what came before the last story, and what comes after.

Taken as its own entity, Portal 2 is an enormous game, with a single-player campaign that’s very good, then a cooperative campaign that’s pretty good, and then an absolute massive amount of DLC and fan-made levels that range from pretty good to oh well. It’s a lot like Little Big Planet, where there’s some tailored content that sets a very high bar, and then a huge swell of player-driven content that tries to meet it.

You can get Portal 2 on Steam, and statistically, if you’re reading this, you probably already have it.

Rulebook Template

Writing rules is very hard. I’ve remarked on this in the past, but a big part of what makes them hard can come in terms of forgetting to mention things. Earliest versions of The Botch didn’t include starting diamonds in the rules, which made the game extremely hard to play.

What I’ve taken to doing in recent designs is start with a Word Document that contains what I consider a solid working template. Anything that doesn’t fit in one of these parts, in this order, needs to be considered carefully:

The Reunion: Setup Mechanic

Here’s the idea: Players sit down and assume the roles of actors reuniting after years apart, who used to work together on a successful, formulaic sitcom. After the sitcom, one member of the cast had a very successful career while everyone else did not – the ‘Star’ of the game.

The mechanic that sets this game up is that each player gets a card indicating their role and the degree of fame they have. Then, starting with the player with the highest value card, players close their eyes – meaning that the player with the highest value card has no idea about how anyone else’s career went, but everyone else can see the people who had more successful careers than they did.

This one-way information is meant to play into the game, because the sitcom was a mess behind the scenes. And the hopeful aim of the game is to create a short story, told in flashback, about what the sitcom was like, about what’d happened since, and about the kind of people they were, all told by the oblivious Star piecing together the narrative of what happened to a life that had nothing to do with them.

The obvious inspiration for The Reunion was Bojack Horseman, which has a lot to say about the way TV comedy gets made. The thing is, the stories of how TV series were made are all so full of extremely strange stories where so many things go wrong, where you can change or replace any given incident and you’d still have a distinct story.

Now, this central mechanic, where there’s a pyramid of knowledge, excites me because it’s a fun puzzle. One player has to start putting together four or five secrets from the things they can be told, while the other players are trying to tell their parts of a story without breaking character. At the same time, though, this isn’t guided – it’s not like Dog Bear where there’s someone in charge of the game who can be told to steer the game to an actual story point.

The really scary thing to me about this game idea is how do I keep it from getting Content Warningy? The whole point is to give players some reign to create, ideally something ridiculous and hyperbolic, but also with a dark twist as to what things were really like. And when you give people a set of prompts about the failures of a creative process, there’s always this part of me that worries people will take it to a really dark space.

In Dog Bear, there’s not just the Boss guiding the game who I can directly entrust with the authority to keep players from being assholes, but it’s also comically ridiculous, with its cyberetch and nanomachines. Not the same thing here. And now, these are the constraints that the design needs to overcome.

Phone Genders

Language shapes thoughts as thoughts flow into language; often we need a word for a thing before we can talk about it meaningfully. We deal with this a lot in academia – much of research is just spending time exhaustively showing a valuable purpose for a name, then putting that name to a thing. The word ludic has a sibling word, paidic, for example, but that word is far less well-known, far less well-shared than ludic.

Language changes what we know, what we can know. Language also is full of features, small and clever and insidious that guide what we can talk about, how we can talk about them.

You might know me as someone who has beef with the English language. A bunch of different, smaller beefs, but one of my beefs is that we have gendered pronouns and almost nothing else. This means that for people, expressing gender can often be about choosing pronouns, which is a feature of language that should be unnecessary.

Story Pile: Voltron Part II: Faces Of Evil

Last week I talked about how Voltron: Legendary Defender is a series of archetypes. It’s a story made up of scaffolding, and what holds it together is a consistant moral and thematic outlook. One of the ways the story holds its form is through its villains, and how they, consistently, are alone.

We’re going to talk spoilers, after the fold.

Continue Reading →The Riddler Sucks

I like superheroes a lot but they sometimes hold onto some really weird things.

Last year, Adam West died. And his death brought with it a lot of nostalgia. The Lego Batman movie hit streaming services, so I got to watch it. Twitch advertised the living heck out of a game about Gotham Villains, and in it all I kept noticing people bringing up shots of some real classic heroes. Cesar Romero’s excellent Joker; Eartha Kitt, the most legitimately criminally threatening Catwoman; Burgess Meredith, who breathed new life into the Penguin.

But there’s the Riddler.

This isn’t my critique, not really; it’s an idea that was brought to my attention years ago in a stranger, brighter, more 90s internet, by the infamous Seanbaby. The Riddler, Seanbaby pointed out, was a criminal who was slightly easier to catch than normal.

I don’t really like The Riddler as he’s represented in a conventional Batman story. The purpose behind him back in the Adam West show and early comics was that he could change the kind of story into a puzzle that the audience could try and go along with. That’s why he posited his riddles as really conventional riddles, things that a kid might have read. Here are some from the old Adam West show, for context.

What does a turkey do when he flies upside down?

He gobbles up

What weighs six ounces, sits in a tree, and is very dangerous?

A sparrow with a machine gun

What has yellow skin and writes?

A ballpoint banana

What people are always in a hurry?

Russians

What goes up white and comes down yellow and white?

An egg

How do you divide seventeen apples among sixteen people?

Make applesauce

Why is an orange like a bell?

Because they both must be peeled

There are three men in a boat with four cigarettes but no matches. How do they manage to smoke?

They throw one cigarette overboard and made the boat a cigarette lighter

None of these riddles really are going to give you any insight into what the Riddler is doing. You’d need to be Adam West’s Batman with his level of moon logic intuition to be able to get from the answer to the riddle to the next step in the investigation.

But

But

When the comics or the show put that puzzle out there, and then usually take a break, or give you a moment to consider it, you’re left with the sudden moment when this comic book or tv show becomes a game.

Resume Reading

A thing I have to do, in the times I’m not teaching, is look for other work. This means that I’m part of our nation’s unemployment system, which often requires engagement with a series of helpful, motivational, educational tools that are about maximising my chances of having my resume looked at by a business. Since I have worked lined up for the next semester, though, I’m not under that much pressure. Since I’m also a massive nerd though, I read that stuff, and I read it and then I go look online for research.

Not the kind that promises to teach you how to make your resume work for you, or the best ways to get your resume read or your top ten tips. Those are largely really bad and silly and wrong, and mostly motivated by a desire to get you to click on a post and are mostly written by someone whose day job is professional blogging intern.

No disrespect to those people, just like, mostly they’re not going to have the tools to really give you useful advice.

In fact, you probably don’t need advice.

Getting your resume made is a pretty basic process. Get it to your coordinator’s specs, that’ll be fine. It really will. They’re not trying to make your job harder.

Continue Reading →Game Pile: La-Mulana

One of the hackneyed games journalist points these days is to compare things to Dark Souls, which is usually done by people who want to evoke a comparison to a control scheme and fixed animations, and maybe some exploration. Who am I to fight a perfectly good trope, then?

Dark Souls is kind of like La-Mulana.

La-Mulana is a single-screen platformer puzzle adventure game where you explore an enormous ruin with a whip in your hand, using a retro computer and your wits to pick up upgrades, unlock routes, overcome monsters with increasing ease, and die. A lot.

An innovation Dark Souls brought to this formula of exploration and death was relatively convenient reloading, dispensing with a classic limited-slots save-game system. In La-Mulana, as a nod to pre-1990s computer technology, you can only save at specific key points, and this makes the game much less forgiving than the otherwise fluid Dark Souls. There’s also an ‘experience’ mechanic in Dark Souls, where you can spend resources to get better at dealing with the enemies you face, and every time you save the game, it refreshes your resources. Not so for La-Mulana.

For some context, as I go on: I’m not good at La-Mulana. I didn’t finish it. I’ve put a few hours of work – and it was work – into this game, and didn’t feel I was making any headway. Also, the person who gifted me this game is very good at this game.

You can get La-Mulana on Steam and GOG.

Up front, though, despite not liking this game, I want to say that La-Mulana is not a ‘bad game.’ It’s vast and there are people for whom its particular movement and mystery are exciting and interesting. There’s a ton, a ton of stuff going on, bosses are varied in a lot of different wild ways, there’s a deep lore, riddles and NPCs and a True Ultimate Boss that – I assume – rewards thorough exploration and mastery.

Really wasn’t for me, though.

So let’s talk about colonialism.

Caillois Indifference

If you’ve been paying much attention to my talk lately, you’ll know I’ve been reading a book called Man, Play and Games by a 20th century sociology academic called Roger Cailliois, where none of that is pronounced the way I thought it was. There’s one thing about this book, though, that isn’t really academically profound but I find funny and interesting.

See, it’s a translation from French to English, and the translation is trying to make sure it uses both consistant wording and academic language. That means that there’s very little vernacular, and we get such wonderful phrases as:

… [Ilinx] inflicts a kind of voluptuous panic upon an otherwise lucid mind.

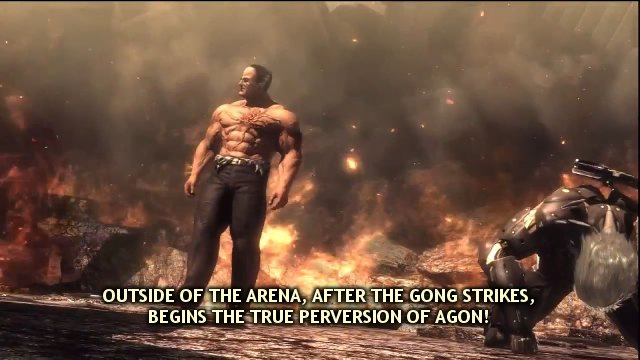

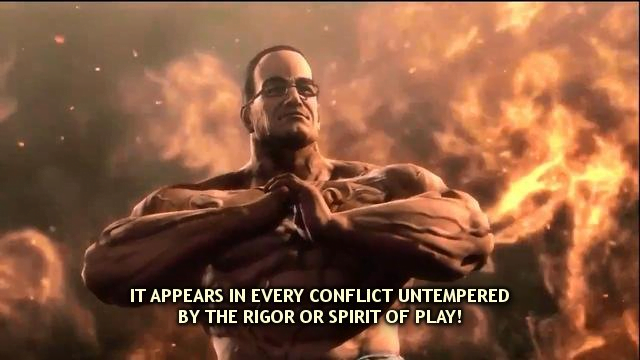

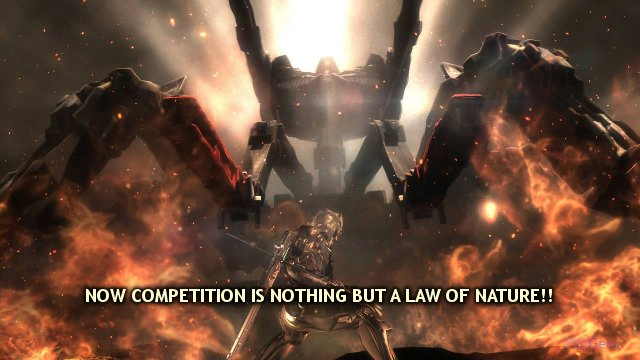

On the Game Study Study Buddies podcast, Michael Lutz pointed out that this kind of talk is a bit like a Metal Gear Solid villain. I tried that out:

Me, I thought about this. See, my feeling was that the takes read a lot more like something from Neon Genesis Evangelion:

But then, as I read onwards, I saw a phrase that stood out, a phrase that demanded its place in a different game.

It’s not a bad book, except in the ways it’s bad.

It’s not a bad book, except in the ways it’s bad.

But it’s funny when it’s recontextualised.

Bad Design As A Swear Word

People like to talk about game design.

More and more these days game design feels a bit like being the kind of people who have strong opinions on coaches in sport. It’s one of those things where there seem to be some sort of generally-agreed upon field of good versus bad decisions, a sort of external commentary option. This is Good Design Because. This is Bad Design Because.

There’s a language we use here, and I’m not sure it’s helpful.

It’s not helpful because the more I hear it, the more and more often people with no clue about games who nonetheless think of themselves as experts, which for now we’ll shorthand as gamer, we hear these gamers talk about game’s design as if there is game design that is good and there is game design that is bad, and the more your work belongs in the first group, the good-er it is.

My favourite example of this is an infamous criticism of Dark Souls 2.

See, back in Dark Souls, there’s this point about how some sections of the world connect to other parts of the world in a way that kind of makes sense. In Dark Souls 2, this is less of a clearly communicated thing. Oh, both Dark Souls and Dark Souls 2 make conventionally-disconnected, teleporting-based maps, it’s not like one does and the other doesn’t.

In Dark Souls 2 there’s a windmill that you climb, and at the top of the windmill there’s an elevator. This elevator takes you from the top of that windmill, up into what seems to be an underground cavern full of lava and with another big fortress inside it that you then have to fight your way through, to get up to another boss you fight in a lake of lava.

This is generally brought out as an example of bad design, where these two elements don’t connect in the same way as the first game did. Now there are a bunch of ways to address this, but the best response, in my opinion, is who cares.

Design is not a bar you fill.

Design is not a percentage that you attain, as you complete the level.

Design is a sequence of choices made within the existing constraints of the project to achieve an intended end. That intended end can change, the constraints can change, the whole project can change, but nonetheless, design is not about attainable end goals as it is about choices.

Evoking game like game is making bad design into a swear word.

It also means that you treat good design like an act of emulation. You’ll treat doing good design as a task of making something that’s like something else. It creates this sort of culture of nitpickery, this conception of design as traits, rather than design as choices.

I’ve covered this topic before – about two years ago, now. Same example, too – Dark Souls 2 elevator, even!

But this one has progress bars, and more than that, this one comes up because I think that while the habit is a problem, it belies a bigger problem underneath itself. It is not that it is bad design to do X is a simplistic phrase. It’s that we bring up bad design when we’re trying to attack an entity, when we’re trying to prove something about it. Many, many times, what we’re trying to say is I don’t like this, and masking that want under the cloak of it being bad design.

It’s not an unuseful shorthand. For example, I still think most of the Assassins Creed games are ‘badly designed,’ because their mechanics do not hold together well in a satisfying way, or connect well to the way those games try to tell their story. Yet many times, especially in tabletop games, we will hear those words spoken to try and argue about the inherent quality of a thing – rather than its aims or its outcomes or its consequences.

We need to get better at being honest about what we like and why. And we need to learn to respect it when someone tells us what they like and why.

Emergence Vs Progression

We talk a lot about games using inexact language. Genre terms are some of the worst – I’ve talked about how awkward our framework is. Sometimes we describe games based on their mechanics, their country of origin, other games they remind us of, the camera position, and even a few games get named based on the creator. It’s not a good system.

That said, let’s put out some Game Studies language that may be useful, maybe.

In half-real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds, Jesper Juul, Dutch Games Studies academic and renowned speller-of-videogames-as-two-words describes a whole range of stuff. It’s a good book, it’s got a lot of stuff in it, some of which I agree with, some of which I don’t, because that’s how academic books go.

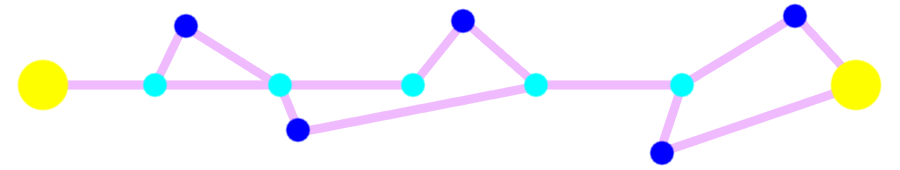

In this book, though, he describes the idea of games of progression and games of emergence. Juul describes games of progression as functionally being about games where a player moves through a sequence of events one after the other. A common metaphor for this kind of game you’ll hear is a route. The simplest version of this could be mapped as something a bit like this:

That’s not to say that they’re strictly linear. You can make a game of progression that has varied sequences of routes that meet up, or even ones that go off in different directions.

The point with a game of progression is that by design they’re structured. Players in games of Progression have every reason to expect predictable responses, and a linear flow. That’s not to say you can’t go backwards in this kind of game’s spaces or anything – it’s that the game has a sequence of expected events the player moves through.

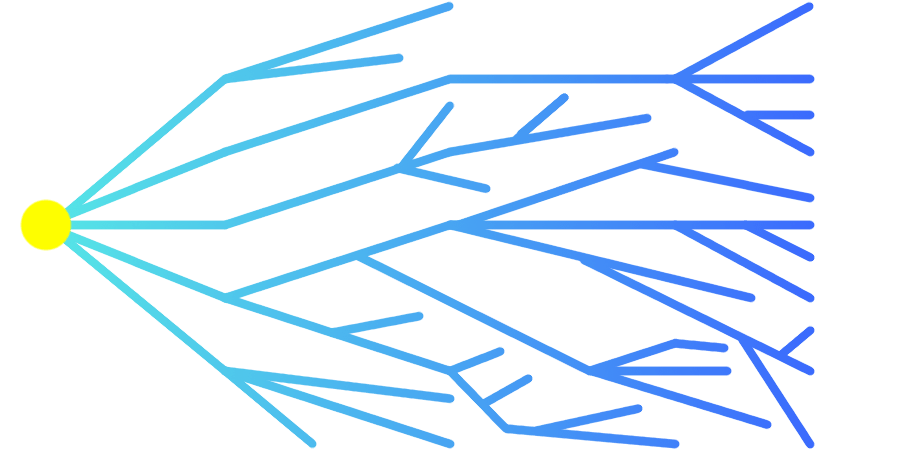

The other kind of game is known as a game of emergence. These games are built instead around rules that react and interrelate. Games of emergence set rules, and then let the play experience put those rules in contrast with one another. A good example of this is Minecraft, where the vastness of the worlds it generates and the things within them that connect to one another are mostly made out of very small sets of rules.

There is a corollary: There’s a common thing called emergent behaviour, where players engaging with a game use things in unexpected ways. This isn’t what games of emergence are about.

A good example of this is how in Quake, levels were designed with large open high areas that you had to reach through circuitous routes, and the explosive force of a rocket was made to let you knock enemies around and to give the weapon impact. Combine the two, and the ability to shoot a rocket at your feet and throw yourself into the air becomes a way to circumvent barriers in the level, to short-cut through parts of the game.

If the Quake levels hadn’t been designed with their bigger areas and overlooks, then rocket jumping wouldn’t be a useful emergent behaviour. If the rocket hadn’t been designed with the knockback it had, it wouldn’t be useful for short-cutting around the level. These are all just parts of the game, that never were planned to work alongside one another, and once players got their hands on them, they found the interaction and created something new.

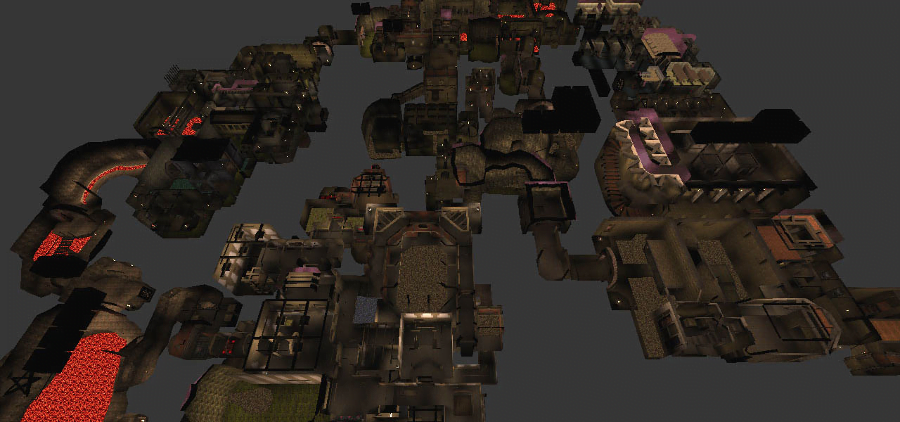

As with all game models, it’s important to remember that these two things aren’t really as simple as they look. While you can point to (for example) World End Economica and see it as a linear game of progression, and SimCity as a game of emergence, games move between these zones hazily. One might be tempted to call Bloodborne or Dark Souls games of emergence because of their nonlinear structure and extremely flexible semi-random combat system, but one can also consider most games in the Soulsborne mould as a sequence of levels. You may do them in a different order, but the progression through each area is absolutely a path from a beginning to an end.

Juul’s short-cut for identifying the games is to look for a FAQ for the game. If the FAQ describes a sequence of things to do, it’s probably a game of progression; if the FAQ describes a list of strategies, it’s probably a game of emergence.

Story Pile: Voltron Part I: A Series Half-Full

Voltron: Legendary Defender has ended. There is now as much of Voltron: Legendary Defender as there is ever likely to be. The story is done, its themes and story are all there; nothing can come in to change the text that is and we can consider what it means, or what it is about, or what it says to us.

If you’re wondering should I watch Voltron: Legendary Defenders, in the broadest possible way, with the minimum of spoilers, then to be up front: This series is great! It’s a cool adventure story with a bunch of interesting, diverse characters, and a regularly shifting status quo that keeps the story from becoming static. It’s very much an adventure story of big robots and fighting monsters in space, rather than your monster-of-the-week model you got in the original Voltron series, and there’s a lot of really cool different stories that make up the whole of the show.

I like Voltron: Legendary Defender.

And I want to talk about what it was about.

We’re going to talk spoilers, after the fold.

Continue Reading →Gamebooks: An Introduction

This has been sitting in my draft folder, with the subject line “Are Gamebooks Games”, since November 2017, and I haven’t deleted it because I don’t know why not. I’m normally pretty quick about clearing things out of my draft box that I’m not going to get to.

I know that this question came up somewhere – someone, probably on reddit, getting mad about whether or not gamebooks belonged on a game subreddit of some variety. Odds are good, I mean, someone on reddit annoyed me. The question persists, though, I think in part because to me, I feel like gamebooks are really underserved as a type of game design, and I kept wanting to come back and deliver a fullthroated defense of gamebooks.

When you find nobody’s attacking your idea, though, it gets a little harder to defend them because you look like you’re trying to feel more important than you are. I don’t want to be that sillyboots, and so the draft has languished, unchanged, as I try to wonder just who was taking pot-shots at gamebooks?

Then again, did I need an excuse to talk about gamebooks?

For those of you who aren’t familiar, gamebooks are a type of book that’s an adventure game. Of sorts. The technology core to these books is that you number entries of story, and at the end of each entry, it tells you where to go to see the next section. This lets the story go in different directions, right?

For those of you who aren’t familiar, gamebooks are a type of book that’s an adventure game. Of sorts. The technology core to these books is that you number entries of story, and at the end of each entry, it tells you where to go to see the next section. This lets the story go in different directions, right?

If you turn to the left, turn to 83

If you turn to the right, turn to 16

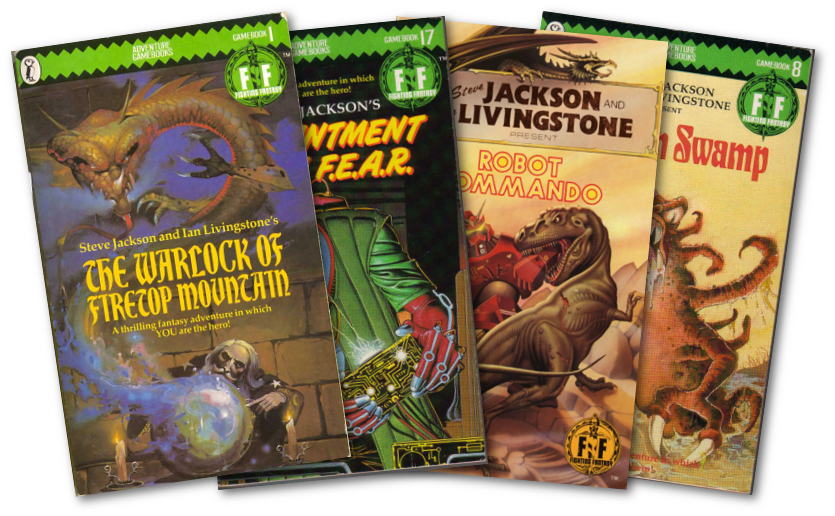

This is a really cool little bit of technology, a sort of basic engine that you see in books like Choose Your Own Adventure, a long-running series that mostly focuses on a simple story where the reader is the protagonist. The more complex Fighting Fantasy gamebook series works on a more classic adventure formula, with dice and dungeons to roll your way through, and the chance to just plain out die.

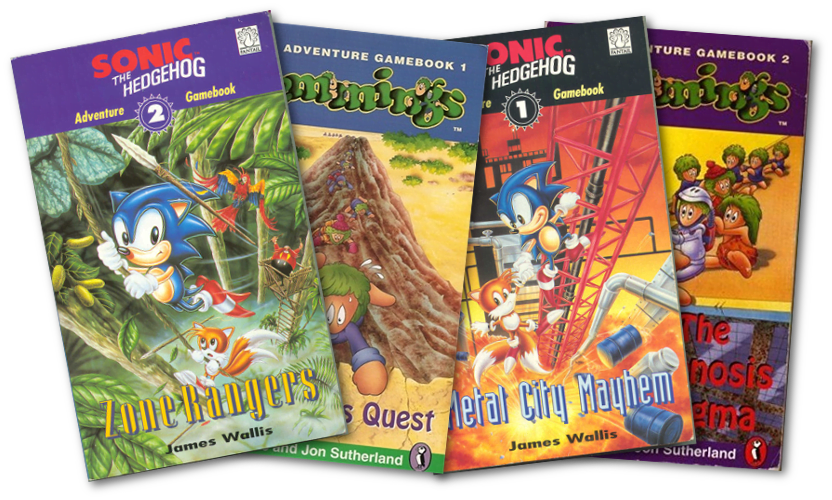

These Fighting Fantasy games were kind of the standard template that were mostly successful. Lots of people played them and they sort of set the rules for how gamebooks got made. They’re not the whole of it, but they were so much ‘the way these games worked’ that even games that wanted a different style of mechanics, like the Sonic the Hedgehog and Lemmings gamebooks,

One of the things that really surprises me about this is how the gamebook technology went relatively underexplored. There were quite a few Fighting Fantasy gamebooks that added some tools – Creature of Havoc, for example, had a neat thing you could do on entries to translate language, which meant if you learned to speak, you could go through a whole different game. One or two of the games added stats – like the Evil stat in one or two of the games to keep you from overusing magic. Night Dragon had a Dread stat that meant the longer you took to get to the Night Dragon, the stronger it was. I even wrote about the spellbook mechanic in the Sorcery! series.

Despite these innovations, they were still built around the very basic narrative of a single character progressing linearly through an adventure like a rollercoaster ride. Some manage to make some exploration, some mazelike structures, so there was something there.

Now, if you’re experienced with Twine, you know a couple of games like this. And twine games can do things like remember, store variables, do random things, and that’s true. But there are other things a physical book can do that Twine has a hard time doing.

I’m thinking on this puzzle, at the moment. I can see the idea that you can make a gamebook that’s about a story of a place; or a book that produces a diagnosis at the end; or a gamebook which is designed to create based on what you do when you play it, or a book that deliberately obscures information from you in ways you have to decipher yourself.

The other thing is, mostly, these gamebooks aren’t actually really coherent stories? They’re mostly sequences of interruptions; you open a door, you enter a room, you find the thing in that room. Sometimes you decide whether or not to open a chest of treasure. Sometimes you don’t. There are games of dice, but few games of (for example) cards.

Gamebooks are a wonderful little artifact, a niche interest, but with print on demand, and more room for more voices, I wonder what we – not just me, but you too – could do with things like light novel gamebooks.

Getting Around The Ocean

One thing I wanna do more of this year on this blog is talking about design. Particularly, I want to talk about things I learned in my three years of monthly games. I want to make sure that information lives here on a blog, a searchable data point, rather than in a notebook with an index and a scribbled number.

I’m doing this, because I want you to know what I’m doing. I’ve done a bit of stuff about the graphic design techniques I use, and I’ll try and keep those up. But I’m also going to try and talk more about decisions, the actual plans involved.

Okay, with that in mind, gunna start on this. Design is the process of making choices to achieve outcomes within constraints.

One of my constraints at the moment is the Pacific Ocean.

If I want to print a game, DriveThruCards asks me to order at least 1 copy before I can sell it on their storefront. They have to print it, then send it to me, a process that takes a few weeks. If I want to change anything, I have to print another copy, and get that sent. This means that a small revision can add two weeks to a work and a large revision can add six or so. This can also mean that sometimes I’ll have to stock up on a game, and realise it’s got a mistake in it after the fact and then I’m left with goods that just fail in some way. This can be a real bummer!

This is definitely a local thing. If you’re in America, the costs are much lower, and the wait times aren’t so bad.

This has me thinking more about digital distribution of goods. Things I can send to people digitally, or small products, are a good idea. Right now, the most basic ideas I can see here are what I consider booklet games, where a small booklet (and maybe some extra things like dice or playing cards) is all you need to play. Another option is RPG Supplements – things like classes, ancestries, equipment or whatnot for various tabletop game systems I like and use. Another option is print and play, which… well, last year I meant to do experiments in that, and I didn’t get around to sharing much about it.

The final option, which is a bit more ambitious, is the idea of an expanding supplement game. A game that starts with maybe 10-15 cards as a print-and-play; and then month to month, I start adding more to the print-and-play, until it culminates with a large, final design and visual aesthetic. This sounds really exciting especially if people invested in it get to request/suggest specific card ideas, and see their ideas implemented!

These are some ideas.

For now I think I’m going to try and talk more about the process of finishing up betas for Adventure Town, then the project currently called The Reunion. The Reunion is an improv game, a single-session RPG which can have a storyteller or not, based around the players all being actors coming together to reunite after their most successful show has ended, inspired by Bojack Horseman and a hidden-identity mechanic I cannot escape thinking about.

Game Pile: Risk of Rain

Risk of Rain is a platform game where you play an alien dropped on a planet. It has procedurally generated levels, a huge variety of characters, and a core, highly rewarding gameplay loop. The game modes can be customised with a bunch of unlockable buffs called ‘artifacts’ that reward you exploring each level you get into. Each level has boss monsters of a particularly large scope, and the game’s difficulty ramps up on a timer. Time spent exploring will typically reward you with more stuff, but more stuff makes the eventual waves of enemies that spawn towards the end of the level harder.

The game has playable characters that eat enemies and gain powers, it has rolling and tumbling movement, it has ranged attackers and melee attackers, and despite playing it for a few years now, I haven’t even managed to plumb its full depths. It’s an excellent, responsive, fast game, whose biggest problem is probably a steep difficulty curve and its camera positions you somewhere around low earth orbit, making the delightful chunky pixel art kinda tiny.

Risk of Rain is really good! It’s a good game, and I like it a lot, and I recommend that you check it out. It’s on sale regularly and it’s not expensive when it’s not on sale. You can get it on Humble or Steam, and the developers are making a sequel, called helpfully, Risk of Rain 2.

And that’s it as a game review. I mean, you don’t need that much space to know this game is pretty damn cool.

There’s more to say, right? There’s always more to say.

MTG: Tapping Out

I’m not going to write regularly about Magic: the Gathering this year.

There are a few reasons for it, but the basic one is that it’s neither easy nor fun any more.

When I started writing articles about Magic: The Gathering the plan was that since I was playing Standard, Modern and Commander, I’d just post the deck I played that week, give it a little twist, and move on, or maybe talk about new sets when they came out. This would build on my old work on Starcity Games under the heading Tact or Friction. I think about that column from time to time – a year spent writing, for money, about Magic to an audience of thousands. I think about it because I think it was such a colossal, embarassing waste.

I wanted, in my heart of hearts, to make the kind of content that FNM-fan Magic players could enjoy. Things that could help the new players step up, avoid the pitfalls of chasing expensive junk rares. I thought I could talk to the design of the game (and in many ways, I was right, a fact I hold to my heart as tight as I can in these moments of despair), and I wanted to try and make the game better and more fun in the ways that I thought it could be. And as justified as I was, I’ll still always be that guy who submitted a spiteful, angry ill-thought out screed and it got paid for.

I know I could do better now.

I wanted to work on Magic: The Gathering content, which has three basic forms that are easy to work with, using my new direction of not being a total asshole. First, there’s talking about a deck, or a deck piece. The second is responding to new releases, doing things like set reviews. The third is to respond to current events, things like big public events, like when I wrote about the data release problem two years ago.

Well, the big events thing ran into a problem in that there wasn’t a lot of happy news around Magic: The Gathering to respond to. People I liked left the company, which was a bummer. The story went directions I didn’t enjoy. There was a boycott of worlds, moments of commentators being total dicks about things, at least one sexual harrassment scandal, and the classic reddit spiral of ‘jackasses saying the same wrong stuff about the game.’ There was an endless maw of news, but it was always spiteful, and tired, and ignorant.

As far as releases go, they were dreadfully uninspiring. I literally forgot to do a set review for Hour of Devastation, back in 2017 and my review of Ixalan was so negative that I actually revised it to be nicer to the set because I know people worked hard on it. I just skipped the set reviews since – I found myself not wanting to say much that was nice about Rivals of Ixalan, which reflected in my ‘set review.’ I barely bothered for the remaining sets of the year – Core Set 2019, I mean jeeze.

Oh, and of course, there’s the importance of Nicol Bolas. I don’t care about Nicol Bolas, I don’t like Nicol Bolas. He’s not a compelling villain (to me), and the way he’s brought in to be behind everything feels like a DM’s pet NPC (to me). He’s had something like six cards in the past two years and every time we get a New, Different Nicol Bolas, he’s eating the space that could be used by something I care about. We could be exploring new mysteries or building new villains or just dealing with something other than more of Nicol Bolas’ plans, but seems that no. No, it’s much better that we keep going back to the well of an omnipresent, eternally important character whose defining trait is well I already thought of that like you’re playing lets-pretend with a little kid.

Over the course of the last year, Standard has been an environment about waiting for it to change. Dominaria was full of promise, but mostly spent its time reminding me how bad Magic used to be. Ixalan promised an exciting new place and insight into Vraska, but no, that’s just another Bolas plot. Guilds of Ravnica promised to return to beloved guilds and plane, but no, turns out that’s also a Bolas plot and also the guilds I liked look awful.

The past two years of Magic: The Gathering have been very much Not For Me, even as I appreciate and am glad to see the new technological developments and improvements the designers have had access to. I genuinely find that exciting. But the environments they’re creating and the ensuing play experience has just not appealed to me, and it has slowly but steadily driven the kind of content I can make, leading to things like the pet cards (which I really liked doing) and the Kamigawa revamp (which was fun, but exhausting).

I’m going to keep playing the game. It’s still a great game. But it’s a game I don’t want to play every week. It’s not a game whose content churn is pleasing to me, nor do I want to be part of.

What Doesn’t Work

2019 Going Forward!

2018 I set down some achievable goals, and I met them mostly. There were some complications with some of it, but I largely feel I met the goals. Particularly the largest, hardest goals were met.

So here’s this year’s clear, distinct, achievable goals.

- One t-shirt design a month.

- Daily blog posts, with weekly entries for:

- a Game Pile article, on (my) Monday mornings

- a Story Pile article, on (my) Friday mornings

- One video a month, released near the 20th.

There’s not going to be Magic articles this year, at least not on a regular schedule and I’ll go into why later in the week. I intend to make each month themed, maybe with a description of what the theme is at the start of the month, but we’ll see. You might notice there’s also not a monthly game release, too, and we’ll get into why on Patreon.

Now, off the blog there are going to be a few commitments throughout the year that I already expect. The biggest one is my PhD needs what’s called an RPR – Research Progress Report. RPR is basically a stand-up presentation where I stand in front of a room full of my peers, my PhD Supervisor, other academics in the field, my sub-supervisor, and try to justify the past two years of reading lots of books and talking about board games.

It is terrifying.

Just imagine standing up in front of a room full of people tacitly asking the question well who do you think you’re fooling. And everyone in that room is an expert and it’s going to be awful. That is the big thing this year, study wise. Maybe that’ll effect the schedule on the blog, we’ll have to see!

Last year had high-productivity points and low-productivity points. Right now as I write this the future log is only 15 articles long; throughout 2018 there were points where it was 60 posts, which I don’t mind – after all, I like being able to take some days off. Still, this year is going to feature a lot of reading and writing that doesn’t get to go on this blog, and we’ll see how that works out.