Story Pile: Minna No Boku No Hero Academia

Curious what you think of the permeability of shonen anime into the general consciousness, as seen in Everyone Making BNHA OCs. – Casey

First things first shonen anime is and has been part of the general consciousness for about thirty years now. My dad knows who Tobor the 8 Man was even if he didn’t, at the time know it was Anime, and Astro Boy is an institution world-wide. What’s more Goku, from Dragonball Z has the cultural cachet of Superman, which puts their general awareness in public attention around about the same level of, literally, Jesus Christ.

That said, there is something interesting about Boku No Hero Academia, a name that I feel it’d be a bit tired to make fun of at this point, and how it relates to Everyone Making BNHA OCs. Specifically, the thing that’s interesting isn’t that Everyone Is Making BNHA OCs…

… its that people feel okay talking abouti making BNHA OCs.

OCs are a really interestingly contentious part of culture. For a start, all creative characters both have them and don’t – the nature of all creative culture as a gigantic remix machine where things we experience become part of the things we create and how it’s all part of this greater framework generation and what we see as originality is really a shift in perspectives or a paradigmatic repositioning and oh god you’re falling asleep – but the other thing is, OCs are seen almost inextricably as embarassing. We use the joke ‘OC, do not steal’ as an inherent joke to describe something people shouldn’t care about, where the speaker is meant to care very much. The Sonic OC is a whole psychosexual bazaar at this point, something most people observe from the outside and awkwardly step around.

Fanart is an interesting mill of media where people often have very one-sided relationships with the work; they do not care about the artist and their opinions or input as much as they care about the other media work the artist invokes. Artists can use fanart as a stepping stone but there is a lot more fanart that goes nowhere than anything else, and the nature of the decontextualising internet means it’s often appreciated by people who have basically no connection to the artist, because they have connection to the media it flows from. Typically speaking, fanart is not a space to get creative – if there’s a character in a lineup from a show that didn’t come from the show, people will almost always see them as not appropriate.

Yet, BNHA has this strange phenomenon where people aren’t just making OCs for it, they’re also comfortable labelling them as such, sharing them, and then, within the framework of the series, using those characters to make fanart of the series. Here, check out this character, who I’m using to show off the way that powers in this really weird and interesting and cool universe could work out!

I don’t think BNHA is uniquely suited for this; you could have seen the same thing back in Ranma 1/2’s heyday, where characters all had ridiculous martial arts and possibly their own ridiculous magical spring. Heck, there was a ten year long roleplay thread on a newsgroup called GRIT that was just about people’s Ranma 1/2 OCs (at first – it spiralled off, as anything would).

What I find more interesting – what I find exciting – is that we’re at a point now where showing off your BNHA OC isn’t seen as inherently ridiculous. We’re reaching a place where when people say I care about this thing, and here is my inclusion in it, nobody says get that out of here. There is a welcoming in this concept space, and…

well, I find that exciting. I wonder how much stuff I’d love better, how much better I’d be at some things if I didn’t feel I was constantly being told I wasn’t good enough.

Telling A Story Through A Game Pt. 2

Here’s a link to the first part. I said I had to go to the tank for this one, and boy didn’t I.

When you want to design a game that conveys a narrative without writing that narrative, and when you accept that all games tell stories, you’re left with a need to construct your game’s components so that they’re made up of potential events, or perhaps better expressed, you’re made up of story components.

One of the things that games tend to have that works well for them is the start of the game, the engagement of the player, is a singular instigatory action; the players’ presence change the status quo of the game’s universe before the player arrived. Now, most of the time the game’s narrative doesn’t incorporate that – most games tend to start from a place where nobody has done anything yet, and the game follows that.

That’s sort of all you need: You need the game’s mechanics to represent the movements, actions or reactions of people. People is a nebulous term, by the way: humans will see people in everything around them. It’s actually really hard to keep people from attaching humanity to the things in the games they play – how often do you see people treat the dice like they have motivation?

The trick then comes in making sure that players can all see the same things as having some degree of personality, of agency to them, something that forms the story around them. And to show the example of how this works, we’re going to look at two great games, with similar mechanics and a complete disconnect between the nature of how they tell story.

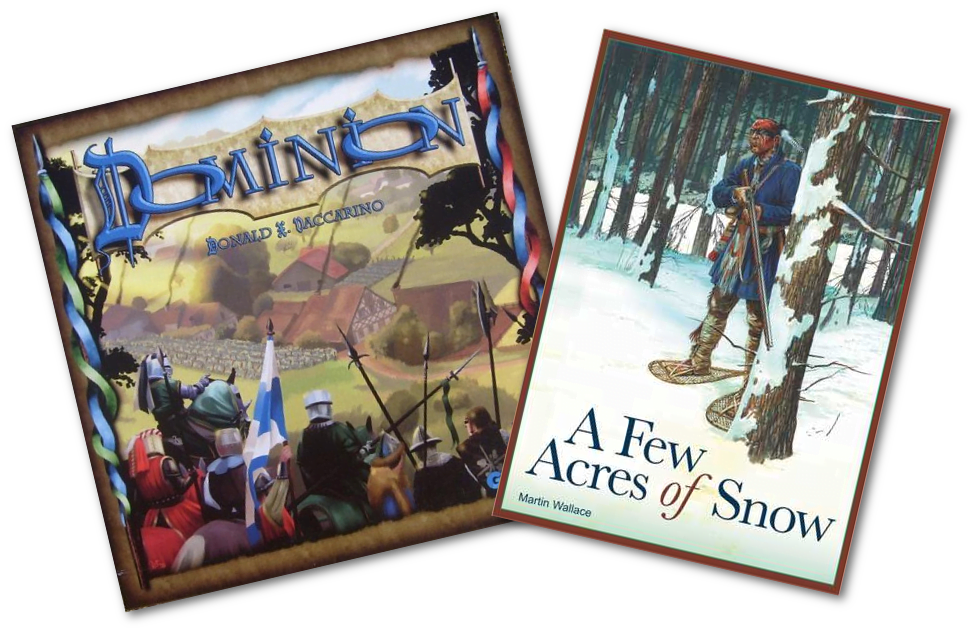

First we have Dominion, the game I tease as being themeless, and A Few Acres of Snow, a game about the invasion of Canada by America in that war they don’t like to talk about. Both games are deck builders, and both games have some pretty simple mechanics that they then expand outwards.

In Dominion…

In Dominion cards are bought from a grid, and there’s a sort of variance in what the cards are, with a very vague idea that you are a ruler, or maybe you are the territory itself, with your deck representing things that exist on your territory.

In Dominion, you add cards to your deck, which then take some time to cycle around into hand. There are cards that represent territory, which is how you achieve victory, there are cards that represent money, which is how you buy cards, and then there are all the other cards that lend some character to your deck.

The thing with totally abstract currency in your deck is that they represent … something. Something maybe. Sometimes, it represents people who work in the territory – silversmiths and blacksmiths. Sometimes it represents objects in your territory – like a moat (even a moat!). Sometimes it represents an object (the throne).

None of these are bad game entities, but when you lay them out, there’s no clear idea for what they all are. Are you building a throne? What do you mean when you have two thrones? Does a blacksmith turning a metal coin into a different metal coin represent something like an actual act of alchemy? There’s no clear explanation, no solid or robust theming. The game has a theme alright, an overtone – it’s one of a sort-of-medieval sort-of-fantasy kingdom, with something like a government, but that’s all.

In A Few Acres Of Snow…

In Acres, the cards represent the actions you as a ruler of the war can take, the actions you can engage with and the ways you can direct troops with a limited range of options – sometimes supplies just don’t show up when you need them, sometimes you have the chance to communicate with three or four cities and don’t have the supplies to direct to them. The mechanisms of that game put the player in the narrative position of a leader dealing with the constraints of a military movement during a time before instant-speed communication.

What this means is that the mechanics of the game become part of the story the game tells you: You’re a leader, you’re making choices, they are all based on communication, and the cards that represent people are people dealing with you and talking to you, people available to you within your limited sphere of communication. One of the best cards in the game for this is the governor – a character that when you buy it, comes into your deck, gets rid of two cards you don’t need any more… and then remains there until you get rid of them with another governor – meaning that over time you can have a deck full of governors, managing beaurocracy, meaning your personal communication is now clogged with fewer bad options but with more dealing with beaurocracy.

Soooo?

The difference between these two games telling stories is that the games’ mechanics require you to change your mental position on what the card entities are pulling your focus to. In Acres, the cards represent opportunities presented to the player, to you. In Dominion, the cards represent things within the player’s space. That’s what keeps Dominion from telling its story; the character cannot be the player, the centerpiece cannot be a thing on the cards.

So, when you want to tell a story through mechanics alone, you need to give the player a through-line they can observe. You need to give them something that can hold the story.

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @Fugiman on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!

What Do I Think Of Visual Novels?

I’m a big fan of the Visual Novel. I don’t just mean that I have a fondness for the form borne out of a period of my life where they were a way to both get anime and smut at the same time when those were two things I very much needed in my life to feel connected to the world around me, I’m actually a fan of the structure.

There’s a lot to talk about here so let’s just dive in.

Accessible Moviemaking

I know a lot of people who want to make movies. For some of them, the cinematography of a videogame camera gave them that option, and you saw early demo-editing Quake levels and replays being made to play with those same ideas of echoing subtitled cinema.

I see the Visual Novel as a less kinetic, but more framing-based example of this same basic idea. Good cinematography, an appreciation of good cinematography, makes visual novels a good avenue to construct scenes as if one is thinking in terms of movies, in terms of what keeps people compelled.

So first of all, they’re a way you can do a movie-sized story on a very, very small budget.

The Point-And-Clicker

When it comes to the game elements of the Visual novel, I feel that as a game type, it inherits well the basic structures of the point-and-click adventure, those low-impact, low-action kind of games that wanted to give you the time to quietly and patiently sort your way through problems that are presented to you. Things like Monkey Island and Beneath A Steel Sky, where the point was not some focus on exciting action setpieces but rather a much more slow, wandering kind of puzzle hunting.

Now, there are four basic puzzles in point-and-clickers you can deal with, and there are two that Visual novels can do just fine, and two they do Not So Fine.

Good: Use Key On Door

Something impedes you from a path ahead. For good conveyance, you want that path to be in some way visible to the player. You need an object that you can carry to the impediment, and then that will get it to go away. Ie, it’s a key and door situation. There’s a door, you unlock it, you can continue on your way. This type of design is incredibly common. Sometimes you’re obscuring the keys, sometimes you’re obscuring the doors, sometimes behind the door there’s just another key, sometimes you’re just collecting completely obtuse keys – but that’s the basic thing. Take an object to an impediment.

Bad: Put Apple In Box

So there’s this thing that’s really tricky to do in Twine, and Visual novels as well, where you have containers. Containers are something some games can handle just fine – I’m told Inform can easily handle it when you put an apple in a box, then pick up and move the box around and then set it down wherever you like – the apple will still be in the box. In visual novel coding… this is trickier.

What this tends to mean is that visual novel games often feature a bit less of characters interacting with the world as a place with a lot of material objects. This is also reflected in the genre – note that most games are not about carrying around tools, as much as they are about inner experiences.

Good: The Language Maze

This one’s a little more common for older games, back before we were voice acting everything. A language maze is – very simply – a series of conversation choices where you need to choose a particular sequence in order to find a point in the conversation that an opponent does something that the conversation would not normally do. Some mazes are really simple – you just ask a character a thing, and you’re given an object. Sometimes, you ask a character a thing, and that gives you some knowledge you’re now able to use later. Sometimes you ask a character a thing, and that gives your character some knowledge you’re now able to use later – like teaching your character to pick locks or something.

Bad: Freedom Of Movement

And now here’s where the point-and-clickers of the past are a little different. The typical form of the Visual Novel is a linear flow of time from A to B. You’re very much moving along a line of time, rather than necessarily having the means to travel between locations. This isn’t to say that’s how things have to be, but it’s not uncommon for people writing visual novels to present them as a single long line of time with you moving along it.

This isn’t to say that visual novels are bad at this – you can definitely set them up to do it. But the default code structure of something like RenPy reflect the genre, where it is very, very easy for the game to just see each play as a series of sequences that check variables, rather than necessarily going to places and letting you move around them more freely.

Scaling Up

Then there’s the things Visual novels can do well that you can lean into and build on in your own projects.

Codeces

Hey, you know how you have all that writing about your game world, or your characters and you want to give people a place to go look for it and read it if they want to? But if you dumped that in the main space for people to read it’d slow everything down and be super boring?

Well, the Visual Novel is a game form where reading a ton of stuff is a thing. In Hate Plus, there’s a reference codex for any character. You find yourself confused by a name? Click on it and it’ll take you to a place where you can look at that character and look at what they’ve done and what you know about them so far.

The Inner Life

It’s almost a stereotype that visual novels have a first-person narrator, often a narrator who is ‘you.’ Doing things this way gives you an almost unprecedented level of access to a character’s inside thoughts, meaning you can see how they think before they act, how their inner dialogue contradicts their behaviour, their anxiety, their stress.

It can also be a fine opportunity to learn that a character is a total butthead, which is a problem that Roommates has.

Day To Day Life

You know that thing about how going to a place is something that VNs don’t tend to do? Weirdly, they do handle schedules well. Because that’s how you use your time, and you can even trigger or chain events based on what you’re doing with your time, today. These can get super complicated, too!

The Wrapup

I really like Visual Novels. If I was better at designing interfaces or had the knowledge of where to start designing interfaces, I’d probably have made some of them by now (Sorry, senp.AI). They let artists do small numbers of works they like, they allow for clean use of arts and assets, and they don’t require a lot of technical knowledge to get started on. They do need you to be somewhat clued in on structure and planning, which is pretty frustrating stuff if you’re not familiar with it – but you can find your plan in the making, too, and restart.

Look into Visual Novels, they’re a great little genre, and lots of fun to think about making.

Telling A Story Through A Game Pt. 1

Gunna have to go to the tank for this one. It’s more than one answer.

First of all I have to unpack that me because my model of games and stories is intertwined. To me, games all tell stories, the question is just whether or not those stories are memorable or interesting or cool. Basically, everything can tell a story, the issue is up to the interpreter as to what makes that story interesting or good. I have a model of the universe that has room for crap stories, something that’s apparently resisted.

Another thing that’s strange is that we’re heavily informed by videogames these days which have lately taken to making it so that storytelling is done primarily in the form of unsolicited interruptions. The typical way to handle videogame storytelling is to segregate story elements in safer spaces, away from places that players can mess them up by interacting with them.

This isn’t to say that removing control from a player to tell them a story is a thing per se – I mean, look at games like Undertale (spit), which deliberately tracks a lot of things you do or don’t do and is willing to trust you to represent how and what you do. This sort of storytelling is a little bit like getting a report card at the end of the semester, but that isn’t to say it’s fundamentally bad. It’s a little primitive, but that’s okay.

Let’s say you’re making a storytelling kind of game – those are sort of inherently biased towards it. Some games, like Funemployed, Dear Leader or Once Upon A Time make it the job of the players to tell story in an effort to get from where they are to where they’re going (and hi, check out The Suits while we’re at it). Let’s set those aside, because in those cases, the mechanism of storytelling is what the players are induced to do by the mechanics. The game is presenting you wit hstory beats to move between and telling a story to other players is literally all the players are there to do. Those games create inspiration and sort of dose players with it, hard.

There’s also games that use ‘story’ as their framework, games like Dead of Winter where your storytelling is literally mechanised: Where in amongst the mechanically-generated story, there’s a chunk of systems designed to pull players sideways into a story that’s sort of structured and framed and bolts itself into the story.

This can sound like a criticism, but please, trust me it’s not. It’s just that this kind of system is easier with bigger games, where you can dedicate a component of the systems of the game towards Telling Stories. This system is wonderful, but to keep it from being boring, it needs a game of a particular scope. You can’t make a game that’s just a crossroad deck (well, you can) without players running it out with only a certain number of plays. You want some sort of mystery for people when these story elements jump out at them.

There’s narrative created by interplay of objects. Even abstract games do this – look at how people talk about the story of matches of Chess and Go, the narrative of how a game unfolds. Like I said, it’s not necessarily an interesting story to anyone in particular, but it’s still a story.

That’s our framework: There are lots of ways to tell stories with games, in games and around games, and there are some sort of ‘easy’ places to design. We’re going to talk a little bit more about methods for designing mechanics that tell stories next time and using mechanics to make players think of stories.

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @Fugiman on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!

Roads Unbent

I grew up – okay, let me start that again.

I lived, from the age of four to the age of fourteen, in a suburb of New South Wales called Engadine. Engadine is where I learned how money works, how to read, what a library was, how to talk to a doctor, about family restaurants and VHS tapes and watched the Beta cases slowly disappear off the shelves. It’s the place I walked with my mother as she went to a business to pick up an actual physical paycheque and hand it into an actual physical bank. It’s the place I tried a paper route.

To say I ‘grew up’ there is a misnomer, though. Because in Engadine, I was in an environment that deliberately sought to stifle what I learned of the world, watching a small number of years left in the world tick down. But Engadine is still a big part of my life, and time to time, we pass through it on the way to Sydney, from where I live now.

Engadine has a KFC and a McDonalds on the highway, meaning that on a long con drive out of Sydney, it’s a place to refuel and restock, and also, crucially, a place where you’re not going to get caught up in a brutal Sydney snarl of traffic if you stop for a while and sit down.

Dad used to say Engadine had a lot of flat ground – it was just all vertical. The terrain of Engadine is all hills, homes perching on uneven backyards, with the biggest flat areas being the football pitch, the mall, and the public pools, which sat across from the school I went to. We would cross the road and do sport on the big field, or in the public facilities to play hockey.

I really do love the public works part of Engadine, in hindsight. There were so many things that were available to me that I didn’t know, or didn’t appreciate. There was a walkway to the Train Station that went under the road, so as a child, I could safely make my way to the station without having to go up a huge number of stairs or some other way cross six lanes of highway.

When we revisit Engadine, though, the thing that blows my mind is how little it changes. Storefronts have changed – different businesses have come and gone and I’m sure nobody there remembers me, nobody remembers what I did or who I was, some nondescript little church kid with a bowl haircut reading Pratchett novels in the foyer. But the shape of Engadine is the same.

I think a lot of this is because of the roads. Engadine’s roads are all… pretty much the same? The big Woolworths is probably a Coles now, the NeoLife offices aren’t there any more (because the bastard who ran them is dead), but the businesses and the people have to follow the shape of the roads, the roads that are laid out on the land as best they can be.

I remember when I lived there I was genuinely confused as to how there were any other places in the world. How would you get there? The first time dad drove us out onto the highway and I saw that that little road I thought went nowhere in fact went everywhere, it blew my tiny mind.

I remember when I lived there I was genuinely confused as to how there were any other places in the world. How would you get there? The first time dad drove us out onto the highway and I saw that that little road I thought went nowhere in fact went everywhere, it blew my tiny mind.

But Engadine is still Engadine. It is older and it is different and it is dressed differently, but it is still a place named for the people who we took it from, wearing on its roads the scars of a culture that should never forget what we did.

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @Garlicbug on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!

Tabletop: 87, 97, 07

What games were popular or big ten years ago? Twenty years ago? Thirty years ago? Well, that’s a question a bit bigger than I can handle with my very amateur sleuthing abilities on my blog, but what I do have is a big ole databse of nerd stuff that I can search in the form of Boardgamegeek.com.With the prompt I have – what was big, – I can’t really, reasonably, do the question any justice.

What I can do however is reach back to years and bring up things that I recognise, that I can point to as having endured all the way – in some way – through to now. With that in mind, let’s do that:

1987

Notable Names: Illuminati, The Fury of Dracula, Arkham Horror, Chainsaw Warrior, Warhammer 40k: Rogue Trader, How to Host A Murder.

Notable Names: Illuminati, The Fury of Dracula, Arkham Horror, Chainsaw Warrior, Warhammer 40k: Rogue Trader, How to Host A Murder.

When we talk about classics in board games, there is this massive gulf between the true classics – the archaeological games, games like Bridge and Poker and more modern classics (and Chess sits in the background with Awari waving very, very old hands). Yet if we want to talk about modern board games, there are a lot of classic games that, here, were even in their second or third printing.

Rogue Trader is pretty much the first appearance of the Tyranid/Genestealer monsters that wound up becoming instrumental in inspiring Starcraft‘s Zerg. Chainsaw Warrior was a game that could best be described as a pre-Doom Doom, a sort of single-player board game where you ran around shooting monsters in a tower before your time and health ran out. I’ve regularly considered making a sort of modern remake of Chainsaw Warrior – a genuine single-player experience for the shooting-a-baddy set.

On the other hand, Fury of Dracula, Arkham Horror, Illuminati and How to Host A Murder are games that have been iterated endlessly, new and innovative twists and developments over years. Trust me, if a game or franchise has lasted this long, the odds are good that it knows something about what it’s doing.

Not-So-Notable Names: Pictionary:Bible and FART, the Game.

1997

Notable Names: Bohnanza, Catan: Seafarers, Fluxx, Tigris & Euphrates, Gipf, Twilight Imperium, Robo Rally, Shadowrun TCG, GORKAMORKA

Notable Names: Bohnanza, Catan: Seafarers, Fluxx, Tigris & Euphrates, Gipf, Twilight Imperium, Robo Rally, Shadowrun TCG, GORKAMORKA

This landscape is a little more familiar to people, particularly in that it has the first printing of now-ubiquitous small-box card game Bohnanza. This deceptively simple, smart little trading-and-set-collecting game with a beany theme is one of the easiest ways you can get people into realising games aren’t all extremely heavy beasts.

And on the topic of extremely heavy beasts, Twilight Imperium! The first edition of Twilight Imperium was ah, let’s say it was both smaller and slower than Third Edition. Think about that when you hear tales of how big TI3E is. Also, check out Gipf, one of the abstract games in the Gipf Cycle, a set of games that set up the ways the other games in the set will work. Supposedly. Or you might just play Gipf on its own.

Robo Rally – which had two releases in 1997 – was the brainchild of Richard Garfield, a man you may remember for creating the TCG with Magic: The Gathering a few years before. Robo Rally is, you know, Robo Rally is fine? It’s not a bad game at all. But anything the man does is going to be overshadowed by Magic. And also Netrunner. That’s a pretty good resume, you know?

And on the note of auteurs renowned for their resumes, there’s also Tigris and Euphrates, which is regarded by many (on BoardgameGeek) as the single best game Reiner Knizia’s ever made, and he’s made lots. If you want to see more about how that venerable warhorse of the genre plays, here’s a review from someone closer to it:

Not-So-Notable Names: Battle Of the Sexes, Tamagotchi The Game

2007

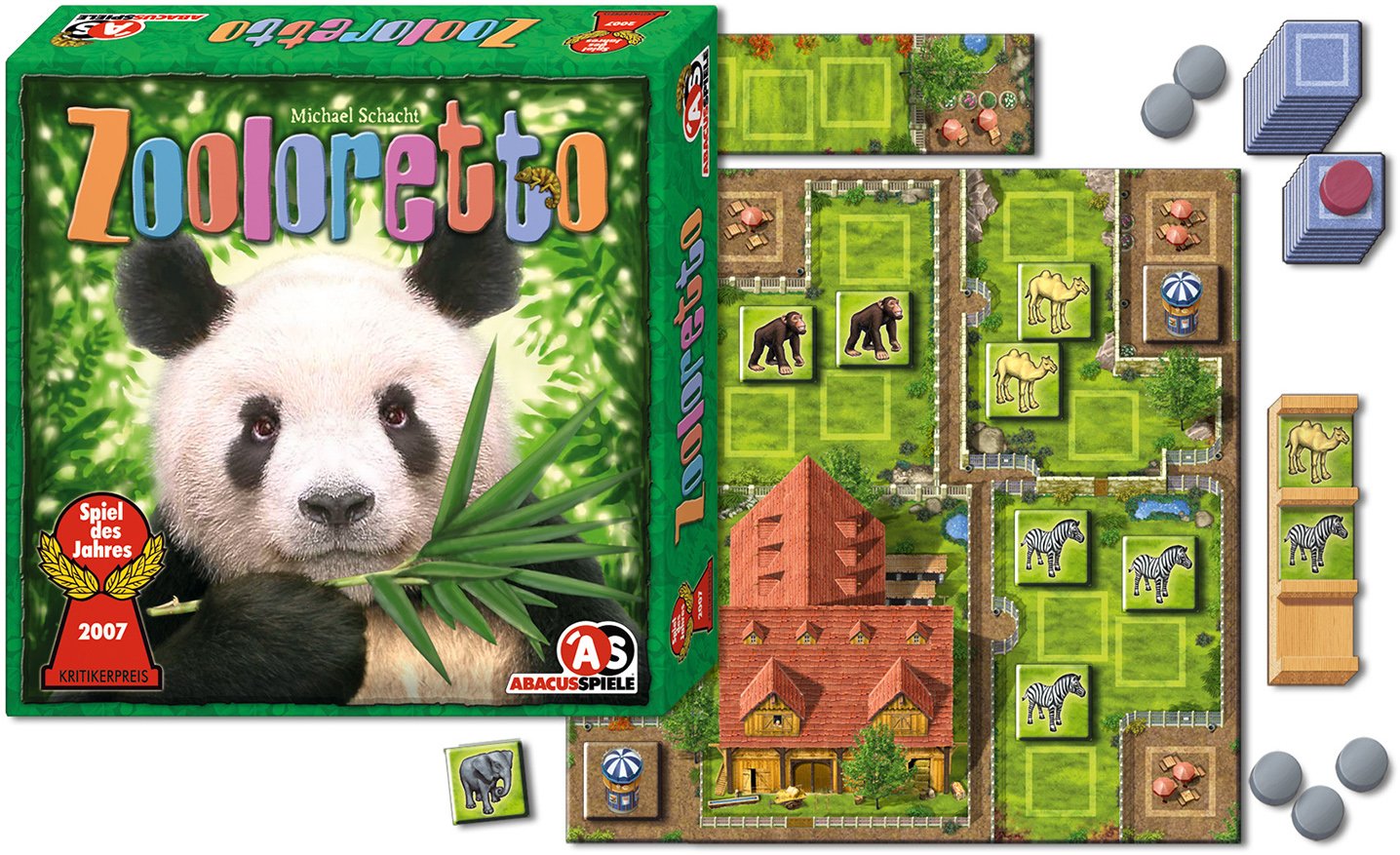

Notable Names: Agricola, Race for the Galaxy, Brass, Starcraft, Talisman 4ed, Galaxy Trucker, 1960: The Making of the President, Tannhauser, Zooloretto, Red Dragon Inn, Cutthroat Caverns, Tammany Hall, BANG! The Bullet!, Caylus, Duel in the Dark, TZAAR

And now we’re in the realm of games that if you haven’t heard of, you might have heard of hearing of. Agricola is a modern worker placement classic, Race for the Galaxy is one of those stalwarts with diehards that love it, and of course, there’s always some monster like me who will always advocate for Galaxy Trucker even though a third of that game is sort of nonsense.

I’d like to make a special shout out for 1960. When I was first learning about this wonderful realm of game design, 1960 managed to somehow both crystallise that board games could be about any old nonsense, and that nonsense could be done with a powerful degree of intensity. It’s hilarious to me in hindsight that of course they’d make games about Presidential elections, because ‘it’s a historically educating game’ is kind of the basic excuse for board games we went to in the hopes we’d be taken seriously.

On the other hand, look at that lineup! Tannhauser uses its UI to overcome the problems of sight-finding in military games. Tammany Hall is one of your classic grindy electoral games, and oh hey, check it out – Tzaar is another game in the Gipf cycle.

Not-So-Notable Names: Beowulf: The Movie: The Board Game

In Summary

Hey, look at that! The past! It happened, and now we’re all marching away from it! Board games and card games are great, just the greatest, and we all walk together into the future where we’ll transcend our material bodies into cyborg bodies! I hope!

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @PracticalPeng on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!

Just Playing 4ED D&D

I was a holdout.

I loved 3.5 D&D. I really did. I was an active poster on the min-max forums. I had lots of work – I mean huge amounts of work – set aside for running 3.5 D&D campaigns. I was planning, in an odd and roundabout way, to make my living selling 3.5 D&D stuff, never once considering the transient nature of that industry period.

I remember sitting down and trying to make my case that 4ed D&D removed too many options from me, it made me do all this work all over again to make characters I liked, and now I didn’t even know if there was anything cool I could connect to. I even said ‘it doesn’t feel like D&D.’

Then at the table, one of our players – working on her research thesis – simply told me that the game let her play. The game meant there was less time for her spent correcting things, researching things, and that she could just play. The game’s dungeonmasters’ tools were there to make it easier to grab monsters, put them together, and just play.

I wound up falling into 4ed pretty hard after that. The first thing is that min-maxing 4ed is pretty good and fun – and I had misunderstood the aim of optimising. The thing is, optimising isn’t about making the most powerful thing you can hypothetically make – it’s about making the most powerful thing within the confines of the game. That’s optimising, it’s building to your limits!

With that in mind, 4ed D&D had really good DM’s tools. It structured enemies and their abilities as if you might have to gauge them. I don’t know who remembers what it was like learning 3.5 encounters but sometimes you’d have to double a monster’s HP on the fly as players spiked it out in one shot, or cut their lifespan in half because players couldn’t punch through their highly technical defenses. Enemies were designed, now. They were designed, not eyeballed!

Do you remember how 3.5 D&D monsters even worked? So many outliers! So many creatures that were ‘technically’ fair, because they were balanced around frustrating either/or mechanics, like the Grick. Remember the Grick? The Grick was a creature with 8 hp, and DR 15/+1. That is to say, they ignored the first 15 HP of any attack from any weapon that wasn’t enchanted at +1 or more. Which meant a Grick was, when you had your first magic weapon at level 4 or so, an absolute laugh – 8 damage was almost nothing to a character who knew how to try to do damage, but 23 damage was a lot for an early play. Dealing 16 or 17 damage five turns in a row was pretty tricky at level 2 or 3, and Gricks, you could fight four Gricks at level 3!

Without a magic weapon!

Anyone sensible would fix that, but 3.5 D&D kept these dang things more or less the same, which was extra irritating! They had a chance to fix them!

So on the one hand you could see D&D 4ed as a major enema on the DMing system, allowing the tools to be a lot more useful for people who were DMing the first time. But it wasn’t just that.

The other thing is that the 4ed ruleset had a very broad, permissive attitude to things in the skill and story system. There’s this chart in the Dungeonmaster’s Guide about why you might want to make a story point a conflict – and it shows a story arcing in two directions: that you should only really make failures about sending the story in other, different directions, which is super interesting by comparison.

The Skill system – which is simplified, it’s true – represented a major change as well, where skills were made a bit more vague, so players could interpret their methods of solution. Suddenly, you could Arcana Things in the dungeon to make obscure systems stop working, but you could also Dungeoneering them or Endurance them to represent sustained effort to break them.

When a player wanted to run a game, when they wanted to sit down and represent the way that their story worked, nobody had to explain it to them. They could read the books, look at how the books talked about running scenarios and stories, and then, those players could make those choices as they started to run the game for the first time.

The Dungeonmaster’s books focused on giving you toolsets, and explaining them well. It was not about creating intricate systems that you had to feed data into, instead focusing on showing you results of those systems so you could easily grab them, but then also giving you the information of how those results were generated.

Then there’s class roles. I know some people hate these, and those people are fine, but those players can just be wrong at me all they like. Class roles already exist in other games; they’re ways that two characters choose to make themselves different to one another so in any cooperative situation, they’re not just replicating each other’s efforts. I’ve done that in games – I’ve been the one player who could replicate another player’s efforts, and I’ve been that player worse when I could replicate another player’s entire character with a class feature of mine.

Class roles are a formal structure for enabling players to build cooperatively. They’re also mostly focused on combat, not on other toolsets; you can reliably point out that Clerics have access to healing type utility powers and skillsets, and Rangers have access to naturey type utility powers and skillsets, and Bards tend to have access to every single thing.

What about the handful of utility goofiness, like magically summoning up birds to talk to or stuff like that? Well, the game doesn’t even tie those things, those special abilities to characters’ classes or roles. Those are now rituals, which means if you want to have access to that kind of special ability, you can just have it if you’re willing to invest in the skills to do it!

You might notice so far I haven’t really been talking about the way this game’s combat system worked, per se. Oh, sure, the monsters as DM’s tools, but not the combat system as players deal with it. I mean, it ties into the combat roles – but you can run a combat-less 4ed game-

Yeah, you can.

Don’t look at me like that.

I don’t know why you’d want to, the tactical combat in this game is one of the fun things it does well – but you don’t have to use it.

The thing is, the combat system, that? I totally understand if you want to take it or leave it. There are lots of games that don’t do combat well, and do other things really well, and you could totally use those. But I like running around stabbing baddies with my Paladin’s big honking axe, and I also like the downtime between those combats spent solving big puzzles and meeting strange people and managing my resources and yes, occasionally flirting with demons because that’s all very complicated.

I like 4ed because it plays well. It’s big, it’s solved, it’s searchable, and you can have a lot of fun playing it. If it doesn’t work for you and your group, that’s fine too. Nothing wrong with that.

But acting as if 4ed D&D is inherently bad? That’s really foolish. It works. It plays. It has inclusive rules that can handle a wide variety of things. DMs are rarely left with the answer ‘I have no idea’ to the question ‘hey, how could I do this thing?’

It just plays.

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @Kassil on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!

Ludonarrative Dissonance in Card Games

Here’s a question: How hard is it to create ludonarrative dissonance in tabletop games which are primarily represented in the players’ heads?

The Concept Of Ludonarrative Dissonance

Crash course! Ludonarrative Dissonance is the idea that the way a game plays or the play experience of a game may have some sort of contradiction to the narrative or perceived theme of that game. That is to say, it’s an idea that crops up whenever you’re playing a game and feel that what the game says and what the game has you do don’t match up. It’s something of a whipping horse in the games discourse, a place we often go to. Myself, I find it a bit too smug as a concept to really deal with, and the people who first coined the term in academia aren’t wild about how it ran wild and was used as part of a wedge to create an implication of some sort of war between Ludic and Narrative elements.

Myself, my thesis – literally, I did a thesis on this – is that the experience of play is creative, and any individual interpretation of the plot and the play is yours and therefore it’s a bit hard for you to say ‘these two things are at odds’ as much as you can say ‘I found these two contrasting things when I played it,’ but that doesn’t make it wrong. So here, some reference material:

Myself, I find the term has a bit of that smug snottiness of ‘you’re posting about socialism from your iPhone.’ It’s very easy to find Ludonarrative Dissonance complaints crop up a bit like…

One of the common sources of the conversation was Bioshock where a game that was ostensibly about complaining about the mechanisms and solutions of objectivism was at odds with the gameplay experience of a game where you hoarded money so you could maximise your personal survival at the expense of others. That particular observation, for example, does sort of beg askance of yes, but the society you’re hoarding money in is a collapsed hellscape full of people stabbing you with knives, but it tends to come down to how you interpret the themes and the metaphors of the play, rather, necessarily that they’re about some objective value within the work.

Wasn’t that great? Alright, moving on!

Where Games Are

The important thing is can you have that kind of dissonance in a card or board game? After all, card and board games are doing most of their work in your head, and it’s not very common you’ll have someone presenting a game mechanic that’s genuinely and obviously at odds with the themes of the work, at least, not anywhere it’s caught my attention.

One example of something that may seem that way in one interpretation is the game Chinatown, which is a fantastic little economic game of deals and trades and math at high speeds. The game’s own manual however, juxtaposes these two lines:

You’re here to achieve all you can and hopefully reach the American Dream.

The winner is the player who collects the most money.

Now you could see this as two lines in contrast with one another, but it’s much easier to read it as just being really cynical, isn’t it? There’s a similar thing in some city manager or economic games, where playing like a purist liberterian may make the game state flat out fail. There’s also the complexity of any game where there’s another player, where you might not perceive a failure in the game’s systems to explain its ideology as a byproduct of that other player hecking things up.

This all makes this pretty hard to put our finger on, but I’d like to point to one example of a card game, that, for me, kinda doesn’t really work that well.

Our Example: CLANK!

CLANK! is a game that’s reasonably well-regarded by players and critics; it won several awards for ‘most innovative’ kind of responses, for example. What it is, in essence, is a dungeon crawler, where you, the players, are moving your little meeples through a dungeon, and picking up treasure and recruiting assistants. This is a well-worn design space, and we have a lot of mechanics for it.

CLANK! is a game that’s reasonably well-regarded by players and critics; it won several awards for ‘most innovative’ kind of responses, for example. What it is, in essence, is a dungeon crawler, where you, the players, are moving your little meeples through a dungeon, and picking up treasure and recruiting assistants. This is a well-worn design space, and we have a lot of mechanics for it.

The thing that sets CLANK! aside is that it uses a deck-building mechanic to handle its loot and recruitment. And at first this seems like kind of a good idea; you can make it so that your cards all represent loot jiggling around in your bags and going clank against one another, and you can even treat it like going bust in Blackjack – you flip too many cards, you have to start again, so each turn has the chance to push your luck and so on.

Myself, I don’t like this.

Specifically, what I don’t like about as CLANK! executes it is has a board and the deck. This means that when you’re moving around, you’re also moving your cards – essentially meaning that your characters have two different abstractions for space. Is this a terrible idea? Probably not, but it does make me wonder about the deck. Deck builders are great for things that grow – but the deck has made itself so that the game sort of represents your personal effects? And as it grows you’re actually unhappy with it? At the same time, the fact that you can get dud draws or draws that aren’t helpful isn’t actually useful, or used for anything necessarily?

Now I want you to understand: My dislike of this mechanic is theoretical. I have not played CLANK! and I’d be happy to find I was wrong if that’s possible. But it still strikes me as an example of where the feel of the mechanics doesn’t work for me in the feel of the game’s style.

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @JulienKirch on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!

Storytelling in Non-RPG Games

This is a bit of a tease of a subject, because if you’ve ever heard me explaining games in general, there’s this phrase I’m fond of using: A Game is a Machine to Make Stories. Not tell stories, to make stories. Every game you play gives you a story, and you may not think it’s a great story or not, but you will always walk away from a game with a story. Since stories are one of the fundamental things that change how people think, it seems to me that this is a pretty powerful tool to put out there!

Plus, there’s the question of What’s a non-RPG game? Consider if you will Assassins Creed II – a game that exists in the Ubisfot mould of A Big Open Thing You Just Do Stuff In. In this game you’re explicitly rewarded for behaving the ways the game tells you Ezio Auditore does; when you match with his memories of an event, for example. You are, simply put, trying to be as much like Ezio as you can. Is that a RPG?

Plus, there’s the question of What’s a non-RPG game? Consider if you will Assassins Creed II – a game that exists in the Ubisfot mould of A Big Open Thing You Just Do Stuff In. In this game you’re explicitly rewarded for behaving the ways the game tells you Ezio Auditore does; when you match with his memories of an event, for example. You are, simply put, trying to be as much like Ezio as you can. Is that a RPG?

Most folk will say no, and I’ll happily concede that, because ‘RPG’ is a bit of a nebulous term. So for the purpose of this conversation, what I’m going to do is try to define what people might mean – generally – by the term ‘RPG.’

An RPG for this purpose is a table-top game where the game primarily gives you the tools to create characters and scenarios for a human to mediate. That’s a rough outline, but it’ll do; because we know what we really mean is stuff like Dungeons & Dragons or Blades in the Dark or Breakfast Cult.

With that in mind, let’s talk real quick about three simple, small examples of Storytelling Techniques in non-RPG Tabletop Games.

The Missing Parent

If you’ve heard me talk about Betrayal At The House On The Hill, you know I’ve had this metaphor well-prepared; in a lot of ways, Betrayal is like an absentee parent. For a portion of the game, it sits around silently, letting you entertain yourself – and then someone trips some meter, some amazing thing happens and suddenly, the game presents you with this bounty of mechanics and storytelling and two different books you need to check through, and look in the box, this one scenario has special cat counters look!

If you’ve heard me talk about Betrayal At The House On The Hill, you know I’ve had this metaphor well-prepared; in a lot of ways, Betrayal is like an absentee parent. For a portion of the game, it sits around silently, letting you entertain yourself – and then someone trips some meter, some amazing thing happens and suddenly, the game presents you with this bounty of mechanics and storytelling and two different books you need to check through, and look in the box, this one scenario has special cat counters look!

I have problems with how it’s executed and how it makes the first part of the game dull, but this tool system is really good, if hard to implement. In the case of Betrayal, it gives you a set of possible semi-random dials that determine what a thing might do, and then the game makes sure that every thing the game might do is cool, and interesting, and stands apart.

This is a great device, a good mechanic, and you should steal it except, here’s the problem: This is hugely effort intensive and it will eat you alive if you don’t keep it contained. Simple fact: Storytelling like this gives you dozens of slots to fill and you can’t make any of them too similar. In this way that opening dull half of a game is a big value for this game; it gives you enough time to forget the exact way the other versions of the game are, and it slows you down enough that you won’t rush to find two identical or similar game modes easily.

The mechanism in summary is randomised set of variables determine a huge number of tailored possible scenarios. The problem with it is it takes a huge amount of effort to make interesting.

The Obtuse Expander

Next up we have the Dead of Winter Crossroads system. Here the system is in summary: At the start of your turn, another player draws a card from a deck, and that card has on it a trigger condition for the event to happen. Could be as simple as ‘visited the Mall’ and can be much more sophisticated.

Next up we have the Dead of Winter Crossroads system. Here the system is in summary: At the start of your turn, another player draws a card from a deck, and that card has on it a trigger condition for the event to happen. Could be as simple as ‘visited the Mall’ and can be much more sophisticated.

The Crossroads system is really nice: particularly because a human interpreter, in secret, keeps track of the info, and the fact the system is being deliberately obscure means you can have it do weird things – like it can actually ask you to search for cards in the deck to set up secondary events, or it can lead to you referencing another deck altogether, or it might even do nothing, leaving a player sometimes eerily afraid of a thing that doesn’t do anything. Plus, because each other player looks at a Crossroad card from time to time, they each learn the kinds of things that can happen but never be sure of what will happen.

Dig this system. It is also effort intense, but not nearly as effort-intense as the brutal weight of the Betrayal book.

The Golden Child

Inevitably, this was going to come up; The Legacy model of games. Legacy games are great, because they let the game have a story arc by dint of adding mechanisms or removing them, transforming the experience of how you play this game. You can’t access that city any more because it is Lost, for example.

Problem with Legacy games? Well there are lots, but it combines problems from the Crossroads games’ level of effort and production values, but it also runs the risk of being unrepeatable. Oh, I suppose if you wanted to combine the Betrayal model you could also make your board game incorporate dozens of permutations of this, so every time someone buys it they might not get the same model of the game’s legacy as the first one but good gracious what the heck are you thinking about.

Applying It For Yourself

With that in mind, here are my three pieces of advice if you want to do this as an indie developer:

- If you make a Legacy game, make it Print-And-Play. Let the pieces be destructable.

- If you make a Crossroads game, hire an Editor. You will need to make this bulletproof.

- If you make a Betrayal game, understand the need for the first arc of the game to be interesting.

Now that said, what about what I’ve done in this vein? Well, the closest I can think to a novel storytelling tool is the game Jiāngjú, which is meant to represent the close of a Hong Kong action movie, where everyone has a pair of finger-guns pointing at one another.

In Jiāngjú‘s largest mode, each player has a hidden role that gives them different values to other players. On the other hand, they know this gives them value to enemy teammates, too. In this case, players have to use their very limited time trying to express a vague idea about who they are to one another in a way that other players can get – while still not giving too much away to their enemies.

In essence, the way to play this form of the game is as if you’re recapping the plot of a long movie, yes-anding your friends as you try to avoid giving away too much of the wrong kind of information. This can mean arguing about who was truly someone’s best friend, trying to find out the edges of who you are, find the edges of what you can give away and not – within three moves of a gun.

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @PracticalPeng on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!