The Khans’ First Onslaught – pt3

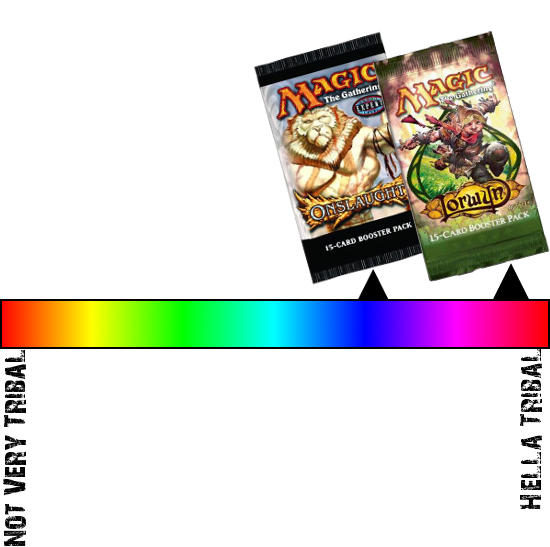

When I compare Onslaught to Khans of Tarkir, it is doing so with a knowing eye of the imperfection of the comparison. Khans of Tarkir was not a tribal set, not in the same way that Onslaught tried to be or Lorwyn was. Indeed, Onslaught and Lorwyn stand on a spectrum of tribality. Onslaught has a lot of tribal – but Lorwyn is bursting with it. Lorwyn is the set that Onslaught looks at and says hey there, whoah, maybe ease back on it a bit.

Honestly, Lorwyn‘s tribal theme is overwhelming. There was basically no option to draft that set if you didn’t open a bunch of lords, for example. The tribal themes meant that mechanics connecting types were really explicit. Some tribes just had ways they worked and they were nice and obvious. Some cards were meaninglessly bad without tribal support. Some cards were overwhelming. You could draft the first booster, find no lords, and just drop, because the format was that twisted around them. That is some messed up junk!

We have this example then that Tribal, mechanically, can go too far. Khans did not go that far – Khans sat on the other side of Onslaught – there’s clearly a tribal subtheme, there’s some thing that connects some creature types together, but it’s not the same Lorwyn-style Lords-And-Chaff design.

The thing that makes this comparison work to me is that the Khans style lets a player connect to the essence of tribal, it works with tribal, without actually needing tribal mechanically. And it does that by touching on the essence of what makes Tribal exciting and compelling – it does it with identity.

The thing that makes this comparison work to me is that the Khans style lets a player connect to the essence of tribal, it works with tribal, without actually needing tribal mechanically. And it does that by touching on the essence of what makes Tribal exciting and compelling – it does it with identity.

The thing is, players are drawn to Tribal mechanics for some reason. Even when those cards don’t seem to have any mechanical commonality, or even problems between two cards that share types, players will often stick cards together because they have that commonality that they feel is important. Goblin Balloon Brigades do not care whether or not they are alongside Goblin Goons, but there are people who will put them together.

Khans of Tarkir does not have an intense tribal theme – not really – but it does include a number of cards that are strong on characterisation. They have feel and they have identity. If you make a Mardu deck, within the space of Khans, you get the feel for how the Mardu cards work. You know what Mardu means. This deck will feature goblins and warriors and probably a demon or two? But it’ll still feel Mardu. You know how to feel Mardu. You attack. You punish. You do not retreat. Power and aggression and honour, all in a pile of terrible violence, tumbling down over the heads of your opponents. That’s Mardu.

Same thing with the other clans – they stand apart, and with their clan mechanics – even as only a few cards in a deck – they hold a feel together, and they give players an identity to connect to. These clans serve to unify under a theme the way that tribal cards do, without necessarily creating the tightly-wound mechanical problems you saw in Lorwyn, or the confused overspreading you’d see in Onslaught.

Khans managed to be tribal (in the mind of the player) without being tribal (in the mechanical constraints). And then you could see all the cards designed for enemy-colour pairs that could fit into different clans, and marvel, momentarily, at the sheer work that went into making sure Khans of Tarkir stood apart from its history.

The Khans’ First Onslaught – pt2

It’s really weird for me to look back and see it like this, but Onslaught is the end of history, in Magic: The Gathering. The new card face had to happen at some point, it wound up working out, and all that, but nowadays, it means that there’s this short, sharp dividing line between Onslaught and Mirrodin that marks one side of the line as ‘the broken times’ and the other side as ‘acceptable for an approachable eternal format.’

It’s not hard to summarise what Onslaught was meant to do. It wanted to establish the morph mechanic and the idea of returning mechanics, it wanted to be a creature-combat focused set that used tribal mechanics, which were already popular with players. It sought to bring something players already liked (tribal) into a space with something new and possibly worrying (morph).

I’ve said in the past that creatures used to suck and it’s not entirely true. It’s more that the 1% best creatures of the history of Magic tend to either be outright broken (Psychatog) or about as powerful as creatures now. The bulk of the rest of creatures, however, tended to be really bad. Token creatures, for example, were seen as a complex rules mesh, something you couldn’t really use very often.

There was also the way that you’d be left with interactions in the set that left me wondering just why.

In case you were curious, yes, this is a two-card interaction where a very commonly played, good rare card from an earlier expansion kills all your lands when you play the Ambush Commander.

In case you were curious, yes, this is a two-card interaction where a very commonly played, good rare card from an earlier expansion kills all your lands when you play the Ambush Commander.

The Ambush Commander has the same cost and size as Siege-Gang Commander, a tournament staple. The Siege-Gang Commander lived alongside the Goblin Sharpshooter, too! But the Ambush Commander was garbage that got you rather badly rekt and the Siege-Gang Commander is still a titan at its job. This is when we were told that red didn’t get good, big creatures, too!

One of the best Dragons in this period of magic was a 6 mana 6/5 with flying and haste and that’s it. One of the other best Dragons was a 7 mana 5/5 that was mainly used to cycle lands out of your library and almost never played. And these are the golden headliner cards! One of the best green creatures was a 4/4 for 4 that gained you 4 life when it died – and that was all!

Oh, and Astral Slide and Lightning Rift were in this format. So to was Akroma’s Vengeance, a mega-wrath with cycling, and Wrath of God, a wrath which was wrath. There was also Kirtar’s Vengeance, if you needed to run twelve wrath effects. If you were in black, there was Mutilate and Infest. Red had Pyroclasm, which would wipe out all the 2-toughness-or-less cards. Simply put, if you wanted to mop the creatures off the board, you were covered, and control decks had ways to force you to over-extend, too.

So.

Wizards of the Coast created an environment that was meant to be about creature combat and the interaction of creatures, where there were numerous tools to clear the board. This meant that in order to be good you either were clearing the board or winning before board sweepers. There wasn’t a deck that fast in black, or white, or green, or god help you, blue. Green had all these dorky little elves that needed to live to tap to work (and got wrathed) and no reach after the wrath. Black had Nantuko Shade and Cabal Coffers, it was on the side of the mass-murdering. White soldiers? God bless them, they were set up for the world of creature fights, not realising they were outclassed.

No, you needed speed.

You needed haste.

Goblin Warchief was part of a cycle, which was composed of Goblin Warchief and four cards that sucked too much to matter in standard, because they didn’t get you turn three kills. Goblin Warchief is a god-damn monster, a creature that blew out the doors when Scourge arrived.

There really was no fix for Goblins. You built a control deck to kill it, or you got killed by it, or you played it.

The creature-based standard of simple mechanics and tribal attacking and blocking led to the generation of which Mike Flores once said ‘who blocks?’

Then Mirrodin came out, and it all got worse.

The Khans’ First Onslaught – pt1

The gamer is a beast prone to seeing patterns, and games are part of feeding that mental need. Some games, like Magic: The Gathering are absolutely rife with this, thanks to cycles and a system of supposedly uniform costing and structuring effects. Any player of a certain time invested with has a general idea of what things should cost, even if they don’t agree with Wizards’ mere rulings on that idea.

When I played the game most actively, buying boosters (and not drafting), I did so with the desire to dig down under the surface of the game and come to understand it. More often than once would I point out old cards and new cards, seeing the way new ones had some element of rules connecting them – a behaviour that wasn’t particularly obnoxious (I tell myself now). I often claimed that the three eras of Magic’s brokenness had been a period of overpowered control (early Magic), overpowered combo (Urza’s), and overpowered Aggro (Affinity). I was…

Optimistically, I had a somewhat simplistic view, but it was an interesting idea. One idea that’s been stirring in my head for a little while, however, is that Khans of Tarkir is the proper replacement for Onslaught. To talk about that we’re going to have to first chatter about just how messed up Onslaught was.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with Onslaught, that block is a god-damned mess. First things first, it was a block with a tribal theme where the two blocks on either side of it explicitly did not service the same groups of tribes, meaning that the set had to rely on its own cards, or on long-term mainstay cards from the core sets. Fine if you were an Elf deck looking to slot in Llanowars (oh wait they cycled out), not so fine if you were playing Soldiers. Odyssey was full of Dwarves and Centaurs, and Mirrodin was full of who fucking cares, Affinity is happening, it is right around you right now it’s in your eyes it’s in your hair who cares about your Onslaught Tribal Zombie Deck Bullshit. This meant the set had a ‘parasitic problem’ – where the bulk of what the set did it did within itself in Standard and there was very little reason to add cards from any other set.

Second, Onslaught was when Wizards had realised that maybe just maybe ten years of Counterspell and Draw-Go strategies might not be ideal for encouraging new players. So Onslaught cratered the power level of blue in its traditional areas of power, and tried to address them elsewhere. This didn’t work – it didn’t diminish the presence or power of Blue, because Odyssey block had just happened, where between Psychatog, Wake, and a full set of good, high-power blue card draw and counterspells, Blue had more than enough power to bully the standard environment. This meant that blue’s tribal interaction was actually reserved, mostly, to dirdly little fliers and drafting red, for some great removal spells. Blue in block constructed was basically nonexistant – even with Voidmage Prodigy in the pool, there was no reason to dick around with the empty-feeling wizard tribe when you could be dropping turn five Kilnmouth Fucking Dragons.

(This was a weird block).

Blue wasn’t the only colour that sucked, though, because black had two tribes, both of which were ordinary outside of draft. In draft? Black was strong, with a bunch of good, resilient zombies and aggressive strategies that crashed in to the redzone. Big enough to block for one turn, then burly enough to charge into the red zone. Then constructed happened and Black had to, uh.

Well, Black still had Cabal Coffers and all the good stuff from Odyssey Block. So black was fine – it just gained almost nothing from Onslaught Block.

You might imagine then that I’d be big on a set where apparently, Blue and Black sucked ass, but the thing is, the other colour that was hosed in this scenario was green – which couldn’t really compete on a tournament level with even blue and black. This was an old day of Magic, where even bad removal was pretty damn good – and green’s colour pie was mostly ‘3/3 creatures for 5 that make 6 drops better.’ Basically, three of the colours were either building into places that weren’t good, or relied on the sets that came before or after them to support a block that was trying to make them less powerful.

The third problem was that Onslaught was the first showing of Morph. Morph was a ghastly fucking mechanic when it first came out. The problems of morph hadn’t been shaken out yet – there were too many situations where a morph was a coin flip. Morph creatures as 3 mana 2/2s were the standard for the other colours – meaning that you would often get 3 mana 1/2s with abilities, or dirdly little 1/1s with a morph ability that would never be relevant. Morph was treated as a special ability, an advantage worth giving up some major points for, creating this landscape of 1/2 and 2/1 creatures. When you stepped out of the draft environment though, there were maybe two morphs whose effects were costed worth your time for actual play – Willbender, and Exalted Angel. Willbender didn’t even exist in a world where it could thrive – it’s been played primarily in older and eternal formats because of its niche power application.

Fourth, Onslaught was trying to be a creature set, a tribal set, back when Wizards were still just struggling with what made creatures good. Time has not been kind to the creatures of Onslaught. In the set there’s a cycle of legendary creatures, known as the Pit Fighters, who at the time we looked upon with awe and hope, only to find, in play, they were god awful. With a few exceptions, it was a generation of creatures that couldn’t match the removal in the world they lived. Particularly sad is the history of Silvos, Rogue Elemental, an 8/5 trampling regenerator – in a block where no black removal allowed regeneration. Nor did the white regeneration. Nor did some of the red removal. Nor did the blue removal. These were meant to be headlining creatures, too!

I guess the final mark against Onslaught though is the real blindspot period its development had. I haven’t the exact details but I’ve heard Rosewater and others refer to the number of things that ‘surprised’ them between Onslaught and Odyssey block. Now, the failure of Mirrodin block is well known and very well understood – Affinity was a titanic powerhouse. But the blind spots in Odyssey block were somewhat subtler – the powerhouse mana control deck lurking in Mirari’s Wake or the overwhelming control represented by Cabal Coffers – or, of course, the odd-one-out in its cycle, Psychatog. In case you’re unfamiliar, Psychatog was an uncommon, part of a cycle, and quite possibly one of the strongest creatures ever printed.

This isn’t to say Onslaught didn’t work. It was a good enough set – but it contributed very little to the greater formats. It’s a deeply flawed block, but it has heart. There’s good idea. There’s good intentions in this set. It wants to be a good block, it’s not a deliberate effort to slow the world down like Mercadian Masques was (and maybe Kamigawa was as well). But we’ll talk more about the high points of Onslaught more later.

A Matter Of A Master Of Pearls

Ladies and gentlemen and other, I am a nerd. I am a nerd of that familiar category that loves to think I’m more capable than people who are professionally paid for a task. I want to talk to you then, about a time I delved into this hubris, and tumbled out the other side.

I have written about Magic: The Gathering design quite a lot. Back in the day, I did it in a fairly formless, low-competence, high-passion way, and while I’m embarassed about it, at the time I had the arrogance enough to feel entitled to talk about it. One thing I was quite sure of was that I wasn’t a limited guy. I was a constructed dork, and I knew I was nibbling around the edges, a space where competitive interactions bled over into casual, where we poached from good players to make interesting or fun decks, or at least their best principles.

That doesn’t mean I didn’t try limited. That doesn’t mean I didn’t read about it.

The Master of Pearls was a Khans of Tarkir rare I skipped over when I first saw it because it was a bear with a morph ability – a clear tempo card, probably for limited. Then the pieces locked in in my head and I started to get annoyed. See, Master of Pearls was a morph whose flip-up ability cost 5 and lasted a turn. In Theros, we got the same effect for 5, and it didn’t go away, meaning that Master of Pearls couldn’t replace the Dictate of Heliod in decks that used it.

At the time I penned a few thoughts about Master. I don’t know for sure if I said it in public, but I cemented in my mind that Master was a card that existed only to mess up limited – it was a limited trick card that was too good in limited, but in constructed, it was worthless. This was a bad card, and Wizard should be ashamed of it. Either make it better for constructed or worse for limited, but don’t let it exist in this strange twilight space.

And then, Fate Reforged:

The interaction here is sharp, so much so I didn’t notice it at first. Lightform can pick up a Master of Pearls and make it a manifest. Then, then, the flip-over cost for it is 2 mana, and gives a gut-clenching +2/+2 at instant speed to everything you have.

Is that amazingly strong? Not really. Your odds of scoring a Master of Pearls off the top of your library is pretty low. You can build to put it there, but that’s basically looking like a combo. If you use Mastery of the Unseen to barf a bunch of manifests up, you can have sort of fun deck holding off, a waiting game while you try and make your opponent find the one that’s actually a dangerous creature that can flip over.

But it’s interesting. It’s something that Master of Pearls can do. And even if it’s not good, it’s a purpose that doesn’t just look like a card that’s designed to kick you in the guts in a limited game. It’s now another turning cog in a game, it’s going to be someone’s favourite ‘combo’ piece. And this sort of low-key lurking realisation is the sort of thing I hope we can all giggle about when we find them in our card pools.

Ruminating on BW Warriors

When I used to write for SCG it was with a fairly standard pattern in mind. You had a deck, you talked about that deck. You made a story out of what you found playing with that deck and you shared it, embellished or not. Most of the time, people weren’t there for the deck itself – very rarely was I providing anyone with revolutionary concepts – but I was often there to offer people the experience of thinking about specific interactions. My most useful articles like this were standardised around Here’s a deck I tried, here’s why it’s bad.

What I’ve been doing lately, inspired by Ted and Jeb, was looking at the influx of warriors to standard by the recent Khans of Tarkir set. There’s a lot to work through there – especially considering the way Warrior as a creature type smears itself across four colours. It’s a known truism that there’s a Black-White warrior deck in draft for players to fiddle around with, which is why both Black and White have Warrior lords and a spell that enhances Warriors.

This is going to be some pretty nerdy stuff, though, so I’m putting the rest below the fold.

KHAAAAANS of Tarkir Spoiler Thoughts

Last night the Khans of Tarkir full gallery was released into the wild, and, since I’m playing Magic right now, I wanted to talk a bit about the cards.

Once upon a time, we did horrible set reviews, where for some reason a writer would pull every single card out of a list, put them in a pile, and then comment meaninglessly on all of them, all of them. Even cards like Crowd Favourites. When I started doing set reviews, I first trimmed out cards that I didn’t like, or couldn’t even make jokes about, and this seemed to be part of a general trend towards discarding meaningless cards. Chances are if I don’t say anything about a card, it’s because I don’t have anything to say. All meat, no gristle!

These opinions are coming with basically no order or pattern. I’ve thrown them into a single post and I’m going to comment on each card as I go. No need to read anything into what it means when a particular card comes up early!

I obtained the images of these cards from the official Wizards Spoiler, but I do host the files locally just so I don’t feel like a leech.

Finally, this is kinda long and we have a big pile of spoilery cards! If you’re planning on keeping yourself pure and chaste of all new card information until after the prerelease, turn away now!

Last chance!