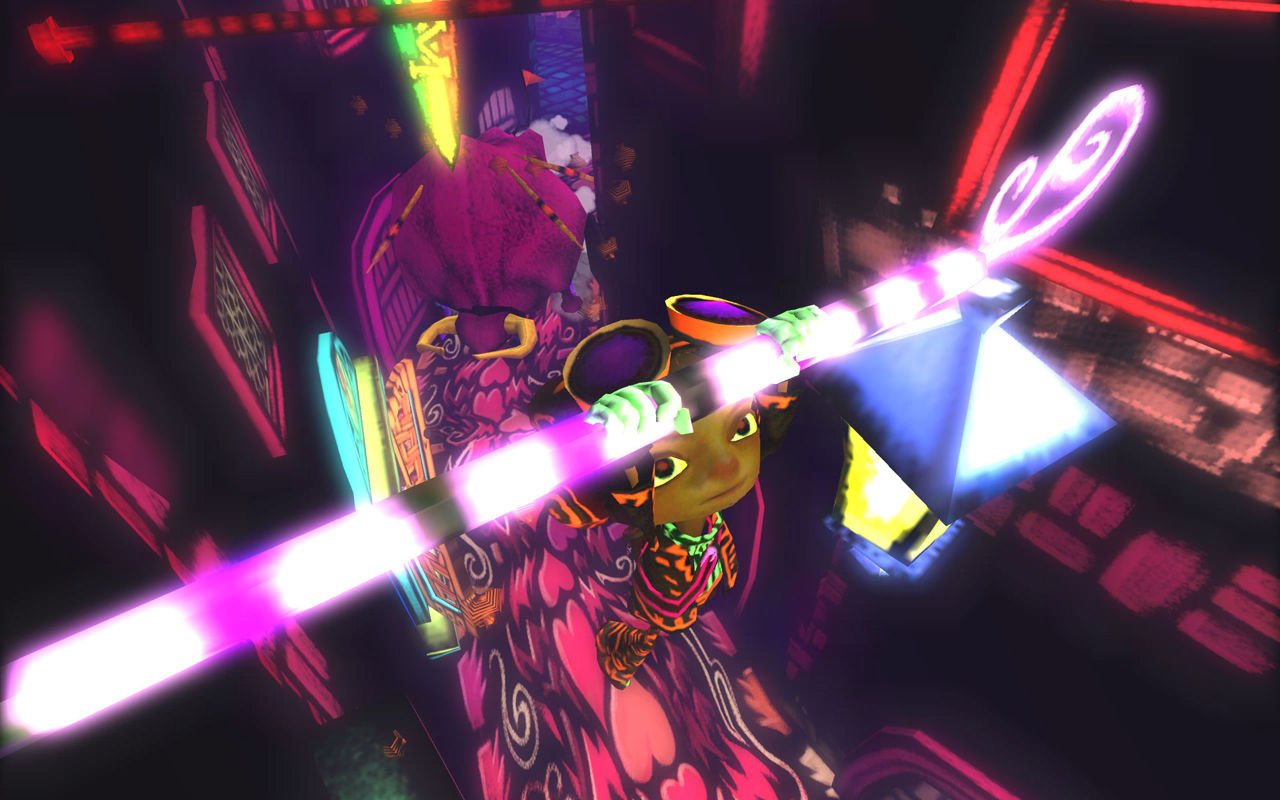

Last year saw the release of Yooka-laylay, a game that launched to thunderous shouts of Okay, a game which some people hated a great deal (because they didn’t like it), and some people hated a great deal (because it’d been edited to kick out a white supremacist, and I’m not linking that disingenuous crap), and some people thought was pretty okay (because they liked it, but didn’t find it that amazing). This conversation put me, particularly, in mind, of the last collect-em-up game that I really liked: The anarchic, quirky and deliberately weird Double Fine excursion Psychonauts.

Psychonauts is the story of Raz, a young psychic who ran away from the circus to join the a summer camp for psychics in the hopes of becoming a trained government operative. It’s a Very PS2 game, in that it uses a twin-stick camera-controller control method, and you run around levels that are a fair bit bigger than you looking for the sequence of things you can Use Keys on except in this game the Keys are your mind, maaan.

Play is broken up into a series of levels that represent physical spaces like a camp and its surroundings, a lake bottom, and a hospital, but also intersperses those with dreamscape like surreality where you plunge into the mind of various people in the setting to explore problems they have as puzzles. Essentially, there are whole levels of the game that are the Keys to use on Doors, and this means that despite this game having a surprisingly small, poky space to work with, it feels really big and expansive, without the need to justify big world spaces.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Cutting the Cake

It feels a bit staid to tell people about what Psychonauts is, because it’s definitely in that realm of Critical Darling status where everyone has had something nice to say about it, where every single game critic has pitched into talk about how great they think the game is, and therefore, how they’re part of the In Club that likes it. It’s also great Critical Commentary bait because the game switches up gameplay models and draws on a broad range of different reference spaces that you don’t see a lot of in videogames. Not none, but just not much, and it’s also now old enough that we can unironically refer to it as a classic.

Thanks to presence on Steam and Humble and GoG and a full-court press by people using it as a springboard to talk about things, I suspect basically everyone has Psychonauts already, and I’m not, personally going to feel like this is useful advice for whether or not you should buy it. I’m not going to hold this game up and say if you want to understand X, play this game, and I’m not going to repeat the story about Full Throttle, or tell you this game has amazing mechanics that we don’t appreciate enough.

The other thing about this game I like is that it’s a dense enough cake of playstyles and ideas that you can pretty much cut any conversation about it in a way to always bring up the things you want to talk about it without feeling like I’m doing a disservice. Is it overrated? Yes, but I don’t particularly care, so we’re just going to cut around that. Is the camera arse? Yes, cut cut cut. Are Double Fine prone to making these middle-of-the-road kind of things that then get praised, and therefore, there’s some greater, broad problem in the culture where a failed PS2 game that attained long-tail success after critical reassessment is emblematic of someone you don’t like getting success you don’t feel they deserve, and this is the perfect chance to talk about it? Well… I don’t think I agree, but you can cut that piece of cake when you want to have it.

I’ll be over here with the bits I wanted to talk about.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Collection As Continuity

When we talk about Psychonauts we often mention about how much of the game tries to switch up the style of play without changing the interface. There’s a section that’s a board game, there’s more than a bit of point-and-click stuff going on, there’s numerous sections that are best compared to high-speed racing or rhythm games. There’s a stealth game, a kaiju game, and a mystery puzzler and I’m still surprised how, when I think of it, there are even more things that I can’t easily describe. I love how much variety the game has in it, and I love the way that the shifting variety lets the designers bail out at the limits of their ability.

The wrestling, for example, in Psychonauts kinda sucks. It’s got one very rudimentary mechanism, and you learn how it works, then the game just permeates on it a little bit. Rather than try and build on this weak implementation over and over, it does three fights to build a nice simple arc, and then you’re off to the final boss of the level.

What this does mean, and it’s a very fair complaint, is that lots of Psychonauts is playing slightly sucky versions of other games. Yet despite this the game still has a feeling of mechanical continuity – you’re never left feeling like the game is different games, you’re always using the metaphor of moving Raz’s body around, or trying to move Raz’s body around.

Through it all, there’s one other thing that creates continuity, that keeps all these different game types together: The collectables.

In Psychonauts collectables range from the very simple and common to the fiendishly tricky, with varying types of reward, and some of them are even devised as gates to other types of collection. You don’t need to do a lot of collecting to finish the game at all – the first time I played it, I finished with something about 20%. Then, at the behest of Foxadon watching me, I went back and recollected everything, and saw how vast the upgrade tree for this game could really be.

I do have one beef here, by the way: If you collect everything, you get a super-double-great-extra unlockable power, just too late for it to do anything worth squat. Would have been nice to run around with it a bit.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Unreality As Reality

One thing about Psychonauts that I like that sets it apart from most of these other collect-em-ups as a game in its genre is that it’s set much closer to ‘real’ than they are. Banjo-Kazooie is about a talking bear and the whole world is being menaced by an evil witch – which is cool, don’t get me wrong, but it’s not the same thing as Raz, who is a boy who ran away from his parents and is afraid of drowning at camp.

By connecting itself to the real world, and using the metaphor of a kid-aimed videogame, there’s a lot going on in the unrealistic setting of Psychonauts that speaks to me. The way the game levels can throw discordant elements together to create metaphor, for example. In Black Velvetopia, the high school environment is literally underneath the streets of the level, suggesting it’s buried. In Lungfishopolis, Raz and Oleander are presented as godly, enormous outsiders possessed of impossible power, as they would be to a conventional lungfish. In Mila’s dance party, she literally and actually has her issues locked away. They hurt, they’re rough, but they’re contained, and they’re presented as an Actual Secret.

There’s also one little undocumented thing in the whole metaphor of Psychonauts for mental health. Some people see the game as making mental health about ‘solving’ people’s problems, as if mental health problems are simple and easily fixed. I never saw it that way.

The thing, for me, is that in Psychonauts, even with magical powers, even with the ability to enter a person’s mind and confront their worst selves, to try and do something for them, to try and help them move on through their problems, even with the most intimate and intense of help…

Sometimes you don’t. Sometimes you can’t. Boyd is still unwell, and a pyromaniac. Raz doesn’t ‘fix’ him. Edgar is still possessed of rage, even if he’s given respite. Gloria may have a cathartic experience, but it’s at the behest of quite possibly changing her memories. Even the final level, the Meat Circus itself doesn’t resolve Raz’s issues, but dealing with and talking to his actual father does.

That unreality of Psychonauts says to us, This stuff is hard, and it takes a long time, and even with supernatural gifts, nothing is fixed easily.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Verdict

Psychonauts features references to a host of mental health problems, such as anxiety, parental abuse, phobias, depression, isolation and pyromania. It’s available on Humble, Gog, and Steam.

Verdict

Get it if:

- You want to try out a quirky PS2- era collect-em-up with a different tone to the N64 era

- You want a game that’s really funny

- You want to listen to an extremely quoteable game

Avoid it if:

- Controller issues bug you

- Collection issues bug you

- Double Fine bug you