C:\> A:

A:\>loderunner.com

Loading

We talk about videogame history quite a bit, don’t we? I keep going back to 1999 to talk about how that period of time had amazing videogames. What about before then? 1994? The dawn of the CD Revolution? Or hey, how about 1989, back when Commander Keen was new?

What about before that?

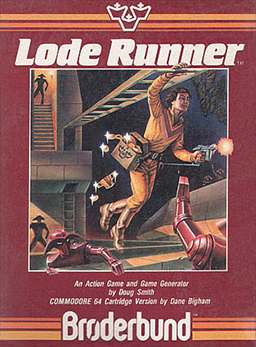

What about if we go all the way back to 1983, and look at a game whose name sounds like a set of instructions. Load, Run.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Working Within Limits

Every single level component of Loderunner was presented to you by the third level. There were bricks you could fall through and bricks you couldn’t burn, and that was pretty much all that later levels added to the formula. Everything was composed of one of those parts; monkey bars, ladders, and bricks. There were over fifty levels in the original version of the game – and that number exploded to over a hundred at some point in new versions – and they were all just built with these simple tools.

No scrolling; no extra content; almost no hidden information. When you look at a Loderunner level in the opening moments, you can, hypothetically, map your path and execute it. The game can’t surprise you very much, especially since the guards act predictably. A guard passes over gold, they pick up gold; they drop it when they fall into a hole. Everything, everything that makes this game interesting is open information, with the few misplaced, impossible to predict fallthrough blocks.

I think Loderunner stood up because it was so good at working with the tools they had. You had maybe twelve tools as a designer – and you had to use them in new, different ways. Some levels are a matter of perfect flow, where you never stay still. Some levels require you to wait, standing still so you can catch enemies that are bringing gold to you. Some levels have a path; some levels have multiple paths.

If you want to look into making a game tight, look into this. There’s a lot of good ideas in these levels.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Ubiquitous Play

Loderunner was an incredible game for me when I was younger because it seemed that everyone had it. It was on the chunky all-green display of the school Apple II. It was on the smoother edged black-and-white of the high school area’s Macintosh. I wasn’t sure why, but it seemed everywhere I went, whether home or visiting a friend, even if they had a wildly different type of computer, there was Loderunner, waiting to be played.

The formula behind Loderunner was easy. It didn’t rely on a particular control mechanism or a particular chip that one system could use. I’ve played the same game with full colour sprites and with black and white ones.

It’s a strange thing to think about. This game has been around in some way or another, for thirty one years. I just learned this week that there’s an iOS version of it, too.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Verdict

You can get it …

Well, you kind of can’t get it any more. It’s too old. There are variants on the game – there’s an iOS version. There’s a Flash version. That original version, 1983 model, is simply not available anywhere I could find it.

Why does it come up, then?

Because this piece of gaming history’s creator has passed away.

I feel strangely mournful about this. Videogaming seems young to us, those of us who are only in our thirties, those of us who can feel our adolescent years just behind us. But Loderunner was made the year I was born. The man who made it was in his twenties. He died this week, and details are missing as to why, but that’s not the important thing, to me.

Loderunner was an incredibly important game. It helped establish Broderbund as a brand. Broderbund moved on to create games like Where in The World is Carmen Sandiego. Those games helped push the videogame as an educational platform, and a transmedia format.

And now, Douglas E Smith, the creator of the game, has passed away – and he deserves to be remembered.