Game Pile: Night in the Woods

We’re going to do something a little special here, this time. I try to keep my writings on games honest, and also useful. For most of you, the useful information is does this game do anything really offensive and is this game an interesting or fun experience to play? With that in mind I’m going to provide that information all in one tight little block – and then, after a fold, I’ll go onto the unfortunate category of a complex but extremely negative and unpleasant issue.

It’s not negative or unpleasant in the ‘beware’ way! This is – it’s – it’s disagreement with a message or a value. It’s not the kind of thing I normally do, because it’s as much a study of a character as much as anything else.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">The Game, As Purely As Possible

Night in the Woods is an active-movement platform adventure which is built around exploratory setpieces. Set in a slowly dying mountain mining town, full of people who grew up there and don’t know how to do anything else, it’s wrought about with rural town menace as writ by the people who live there, not by the people who think anything outside of the New York Suburbs is a grim forest filled with the Wildlings.

What you get when you play it is this wonderfully sad place, the sort of bubbling form of human civilisation you get in the spaces that an older, crueler but also more wealthy world carved out of the wilderness, as it slowly bleeds to death over the course of days. There are murals to history, symbols and monuments to the town’s own specific culture that live in cupboards where nobody needs them, because nobody cares. It is a grim and sad place full of people defiantly struggling onwards because there is nothing else to do, nowhere else to be, and a person’s way of life is not a thing that changes easily.

It is a place full of people who did not have choices.

Populating this town is a cast of young people living in systems created by other people and doing the best they can care to do. There are your friends, the ever-loving Gregg, his boyfriend Angus, there’s Bea, there’s… other characters… as well… with names… like Mom! And Dad! And yeah anyway.

You play Mae, who has returned home from college at a point that is noteworthy and people remark upon it, and the structure of the game is somewhat akin to a point-and-click adventure game. Rather than carrying around an inventory of things to locations to see what reacts differently, you’re just dragging around Mae and looking at what she reacts to differently, where she guides you onwards next. This is all through a beautifully realised, pretty little town of dilapidated yesterdays.

The game does do sideways things – little mini-games where you play bass guitar or try to find someone missing or shoot crossbow bolts or fight with knives. This breaks things up, which is an interesting need in a game that, for lack of any better term, is mostly about frittering away time doing not much special.

As a pure game, it’s a bit like a really low-budget version of a Naughty Dog Uncharted game. You mostly get to control a character moving around a space with responsive controls trying to work out if any bits of your environment are things you can stand on, will react if you check them out. There are setpieces, sudden shifts where the game says okay, now pay attention to doing things this way, with slightly awkward controls that you quietly hope won’t be used as central to other scenes.

As a pure game, it’s a bit like a really low-budget version of a Naughty Dog Uncharted game. You mostly get to control a character moving around a space with responsive controls trying to work out if any bits of your environment are things you can stand on, will react if you check them out. There are setpieces, sudden shifts where the game says okay, now pay attention to doing things this way, with slightly awkward controls that you quietly hope won’t be used as central to other scenes.

There really isn’t that much like this game out there. It’s an adventure game where your challenges are frittering away an afternoon with a friend, a dating sim but the dates are with friends, and a horror story where you never see the monster. It is an excellent indie game made by people who, by all accounts are Not Awful.

#fff, 1px -1px 0 #fff, -1px 1px 0 #fff, 1px 1px 0 #fff; -webkit-text-stroke: 1px white; padding: 30px;">Verdict

You can get Night in the Woods on Steam, GOG, and Humble. It’s a cheap game and you can probably finish it in an afternoon.

Verdict

Get it if:

- You like adventure games but don’t like feeling like you’re waiting for characters

- You like exploring very normal, very mundane spaces

- You enjoy a feeling of creepy wrongness

Avoid it if:

- You’re big on achievements

- You want every part of a game you buy to be good

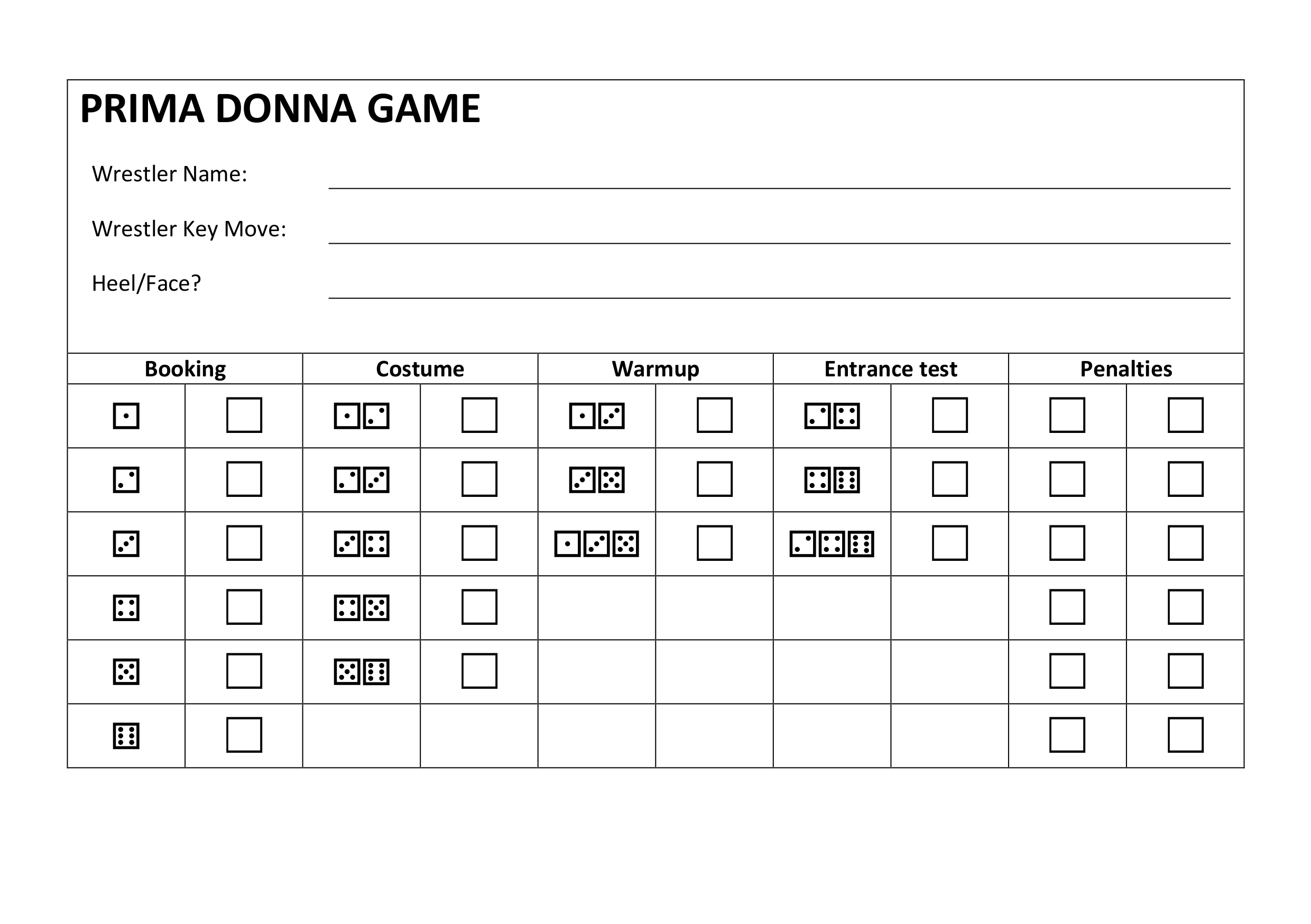

Project: Wrestling VHS Game

The Pitch: It’s a roll-and-write VHS game where you’re trying to get last-minute preparation ready for a big wrestling match. While you’re doing this, though, there’s a prima donna wrestler favoured by the company who randomly interrupts you to make your life difficult!

Details

The genre for this game, VHS Board Games is something you might recognise as modelled on Nightmare, the Video Board Game. To play these, you sat down and played a movie and tried to play a board game as you did it. The video would interrupt the play with occasional tasks that made your life harder, slowed you down or wasted everyone’s time, but could also award you bonuses.

In this game, the video provides interjections not from a gatekeeper or anything, but from an INCREDIBLY well-financed prima donna wrestler who, for this event at least, has WAY TOO MUCH CLOUT. They can BOX YOU INCONTRACTUALLY or THROW YOU OUT OF A BOOKING MEETING or want you to PRACTICE A PROMO WITH THEM and you HAVE TO DO WHAT THEY SAY!

We have a means to get this video to people digitally; we can just put the videos on Youtube. We have means to get them made, casually – any webcam fan who wants to cut a bunch of wrestle promos can do it with an even vaguely appropriate background. We can make it then, so the whole game distributes online, and you can just change the game by using a different video to set a different tone. Each wrestler can introduce their own mechanics – dice-rolling mechanics, inflicting penalties on people, making fast choices and so on. We can even make the components print-and-play!

Needs

We’re now looking for people who can be The Prima Donna, or who are interested in recording 10ish (??) minutes of video of themselves as a wrestler mugging for the camera, cutting the silliest promos and setting ridiculous, arbitrary rules while everyone else is trying to finish a roll-and-write game. We have an actual example of a roll-and-write sheet for the players who want an idea of how the game’ll work! So, if you want to be a goofy wrestlersperson…? Maybe get in contact? At the moment this project makes Zero Dollars and probably only ever will… but if you’ve ever wanted an excuse to cut wrestling promos and roleplay being a total butthead to randoms, well… it’s an opportunity!

So, if you want to be a goofy wrestlersperson…? Maybe get in contact? At the moment this project makes Zero Dollars and probably only ever will… but if you’ve ever wanted an excuse to cut wrestling promos and roleplay being a total butthead to randoms, well… it’s an opportunity!

Also, I cannot currently afford to actively comission this game project! I do not know if my state of money will change or how your relationship to the potential payment would work out! Do you think you have the skills for this? Are you interested in the idea? Feel free to contact me, either via the Twitter DMs or by emailing me!

This Exists: B.O.B.

I said I’d say something about this and I never did, and this sucks and it’s in my head and now I’m going to share it with you. For as there are good things in this world, there are dark and miserable reflections, and with Christian Replacement Media on my mind, let us speak now of some of its worst examples.

In the late 90s there was a ska boom. Ska music got on the radio. There was also the peak era of South Park, as a generation of teenagers tried to convince their parents that they didn’t care about your opinions, dude and they liked edgy, powerful, dangerous media like this thing about children talking to poop.

Two media trends, two chances to capitalise and milk money out of other Christians? Well, of course it was time for the Christian Replacement Media machine to get involved and get involved hard.

“What,” you may be asking, “the fuck was that.”

That, my friend is the evil mirror to Five Iron Frenzy. It is the fundamentalist-enough Christian alternative to South Park’s visual aesthetic branding and opposition point to the radio’s sinful Mighty Mighty Bosstones. It is a musical Waluigi, an entity created entirely in opposition to values rather than expression of values. It is ash. In as much as art can be, it is sin.

By the way, boy, the people on the Mexican border really had a problem that they weren’t getting enough Americans telling them about Jesus. Mexico’s a country with a real problem with Christianity, right? Let’s set aside the Anti-Catholic and patronising probably-Racism of Mission Trip To Mexico and instead examine what I feel is probably their worst song, Homeschool Girl.

Public school is full of drug addicts, boring, and lies to you. But Homeschool girl, well, she’s super great.

Augh I’m listening to it again.

And

just

so

fucking angry.

It literally exhorts how good she is at preparing him stuff! It holds up how smart she is by how many grades she is ahead except because she’s homeschooled that doesn’t mean anything, since the person telling you that isn’t a fucking teacher! This is literally propoganda for a lifestyle that I know’s inflicted tremendous harm on people!

Sometimes you can think about the impact of a piece of art in terms of what it made seem normal, what it impacted, who it really influenced. And I am sadly certain that there are people, right now, homeschooling their kids, who are doing it in part because when they were young teens, they heard this song and it helped to form what they thought of as ‘normal.’

Hmm, let’s see, other countries, homeschooling with some overtones of sexism, what about –

Oh yeah, Abstinence!

Fucking hell this fucking group of fucking dickheads.

Okay okay, not going to talk about the lyrics or message of this media – the pain of having had sex? the fuck, you’re doing it very wrong – but I’m going to talk about how boring this ska music is. It’s very competently arranged, but very poorly mixed, and if you listen to all this stuff in a row you’ll be struck by how all BOB songs more or less sound the same.

All their album is up on Youtube, if you give a shit to go listen to it. I think their least obnoxious track is I Saw Pastor Dancing, which is just intensely cringey.

Oh and if you’re curious: Yes. I owned this album. And I owned it instead of owning All The Hype Money Can Buy.

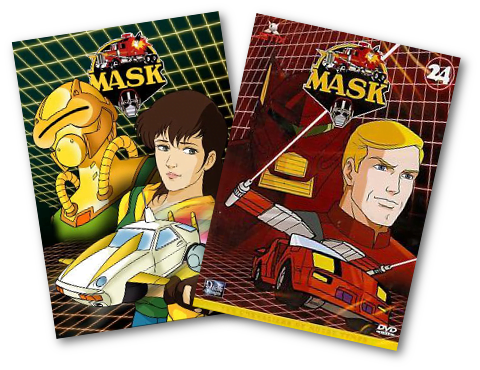

M*A*S*K – A Platonic Ideal

There was this comedy web cartoon called Cheat Commandos, whose tagline was Buy All Our Playsets And Toys! If you’re at all a fan of this era of tv, and I guess somehow I am, you might be inclined to remember this as being connected to the GI Joe cartoons of the time – which Cheat Commandos very clearly connects to. The toy lineup for GI Joe was ubiquitous, too, row upon row of them in the toy stores or the aisles of supermarkets, little toys designed to make kids happy and also extract their pocket money. This was the Reagan Era of media, the period when advertising directly to children was deemed Okay Now. GI Joe wasn’t actually a brand made for this – that’s a toy line that existed since the fifties, a venerable senior of the merchandise wars. When deregulation hit the toy media market, it wasn’t GI Joe that shifted over first. Heck, it wasn’t first out of the gates; the very first media like that was stuff like The Gummi Bears, which happened because Disney could make a TV show that fast to try and sell plush toys (I understand).

GI Joe wasn’t actually a brand made for this – that’s a toy line that existed since the fifties, a venerable senior of the merchandise wars. When deregulation hit the toy media market, it wasn’t GI Joe that shifted over first. Heck, it wasn’t first out of the gates; the very first media like that was stuff like The Gummi Bears, which happened because Disney could make a TV show that fast to try and sell plush toys (I understand).

We all know, now there’s a sort of template for all these shows from Dino Riders to Inhumanoids to Zoids’ first appearance to the Street Sharks to the X-Men cartoons that they were all more or less the same basic idea to try and sell you a toy lineup. Yet when you go back and look at those series and really consider what they’re doing, what they’re trying to do as the way they fill time selling you a toy, there’s almost always something interesting to talk about. It can be a queer reading or elevating pulp media with surprising value to it or attacks or critique for racism or transphobia or –

There’s almost always something there.

Moviebob recently stated in Really That Good that the Transformers movie being good may have been an accident but its accidental existence doesn’t change the fact the movie is good. Looking back on Silverhawks and Thundercats shows some drop of something that’s there, worth talking about, worth revisiting.

That’s why going back and rewatching M*A*S*K has been astounding. There’s almost nothing in M*A*S*K to talk about! If you want to remark on anything in this series it has to be the naked emptiness of it, the way its enormous cast of characters had three and a half personalities between them. Or maybe the way its racial diversity is somehow more represented by white guys doing accents. You could try and build something out of the way that several of the characters are the same basic person, or the way the series gave its most boring, easiest voices multiple new masks and vehicles.

I think the one thing in M*A*S*K that really stands out to me as interesting, the one thing this series does that’s kind of cool is when the M*A*S*K signal calls, every member of the squad is shown interrupting whatever they’re doing, no matter what, and bailing. This gives a chance to show that the character is a character, who has something going on – like you see Bruce bailing on a meeting with other inventors, or Alex rushing a pet feeding. That’s almost all you get to demonstrate anything about the characters, though because after that point, they are nothing.

M*A*S*K doesn’t have characters, it has the accents Doug Stone can pull off.

What I’m saying is, when people joke about a TV Show, from the 1980s and early 90s with interchangeable, underdeveloped nothing characters who existed to only advertise and encourage the sales of toys to children, they’re almost certainly talking about M*A*S*K.

Something I Like: The Show!

The Show, for all that its SEO is pretty rough, is a smart, fun little Australian-based web show that to me stands out as a wonderful example of a web-era version of a Variety show. When you couple with the puppets and the preference to oddball short gags it reminds me of a particularly hyperspeed version of the Muppet Show.

I like it, it’s good and it’s worth sharing.

MTG: Blue Pirates

With the arrival of Ixalan comes new flavour, new themes, new mechanical things and with that comes new discussions of how Wizards shouldn’t be doing the things they’re doing, because we’re much better at it than they are. Perhaps.

One topic that’s been brought up is why are the pirates blue? Now, this is one of your classic types of arguments: An argument that doesn’t mean anything, resolves itself, but is still fun to engage with. Far be it from me to complain about fun!

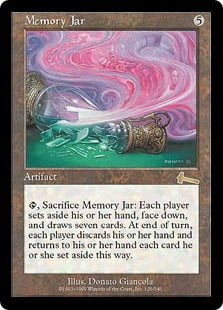

Pirates have been blue in Magic’s history for a while, following an annoying pattern of ‘well we put it in blue and now it’d be just rude to not keep it there’ that defined Magic’s past. They first appeared in Mercadian Masques, a set whose whole theme was ‘uh, sorry,’ and yet despite that still had two cards in it broken enough to get banned in block constructed, because of course.

Now, back in Mercadian Masques I really disliked the pirates as presented – but there’s a lot of stuff in Mercadian Masques that’s a problem (rebels in white? c’mon). I remember reflecting on how Pirates didn’t belong in blue at the time, and, at the time, I was right. The opinion has refined a little though. Pirates don’t belong in just blue.

Still, we’re talking about now, so what are some things about pirates that do fit, wholly and squarely in blue?

Theft

One of the defining actions of the pirate in fiction is taking things that aren’t yours. It’s sort of what defines a pirate. Things like navigating into the ocean, focusing on the self, indulging in strong liquor and being willing to fight over needless nonsense, if it lacks for theft isn’t actually being a pirate – you’re just Jimmy Buffett.

Blue steals! Blue is the colour that steals the most! In fact, blue is the colour that gets the most efficient forms of long-term theft! It’s an area it overlaps with black and red, too, so, yes. Pirates steal.

Change Of Identity

There’s this old rhyme used by outlaws in America.

Oh what was your name in the states?

Was it Johnson or Jenkins or Bates?

Did you kill your wife?

Or flee for your life?

Oh what was your name in the states?

Grim, but it showed a part of the American outlaw life that was by no means unique. Without any kind of central government to control identifying information, outlaws in the wild west would change their names and in so doing, shed entire histories, letting them choose who they wanted to be. Usually, they chose poorly.

This is true for sailors and pirates, too. It wasn’t an uncommon thing for pirates to change their name, head to the docks, and head for nowhere. There’s a simplicity to a life on the sea. Once you’re out, you’re out, and there really isn’t anything else you have to worry about but what’s on the ship. It meant that whoever you were or whatever you had to say, it wasn’t like anyone was going to google it.

Now you can make a case for these sorts of things not being a result of personal choices – after all, many criminals commited crimes of desperation then fled because they knew the society they were in wouldn’t handle it fairly or reasonably. The blue mage could then argue that choices in the face of circumstance are still choices and then you’re in the larger argument about the colour pie, period.

Escape

For all that pirates have reputations as being combative and taking what they want, it’s worth remembering that most of them had fast ships rather than warships – they wanted to catch up to people and take their stuff, but they also wanted to get the heck out when they were at risk of taking on more than they could handle.

Conventionally we see speed as a red thing, or a green thing – Flash creatures leaping in as predators, or red’s hasted beasts. Blue doesn’t get speed in that way. But blue does get the thing speed is used for: Evasion.

Information As Currency

What’s the conventional thing Pirates are All About? What’s the thing most pirates go out of their way to find? What is usually the object that instigates entire piratical stories?

What’s the conventional thing Pirates are All About? What’s the thing most pirates go out of their way to find? What is usually the object that instigates entire piratical stories?

Treasure maps!

The nature of the pirate as someone driven by information should stand larger than it does, perhaps because the typical pirate movies we’ve seen have been well, thoughtless silliness and nobody reads books any more, apparently. In none of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies is much made of knowing things, or of discovering things as much as the treasure-map stage of things is replaced with a sort of ricochet-from-point-to-point approach.

None of this is to say that people who dislike blue pirates are wrong (though they are, sorta). It’s more that I thought about it for a little bit and realised how neat it was that many pirate things are Very Blue.

Bubble-ical Discipline

Did I really choose that title? Is that what we’re going with? Mmh, well, okay.

If you’ve spent any time on the internet delving through the Youtube archives of people telling you about things you’d never heard of that suck, chances are good you’ve run into the ouvre of Christian Replacement media I was raised in. you’ve seen attempts to make Christian musicals, you’ve seen the Christian animations, and you’ve probably even come across the Christian superhero stories. Which suck.

If you’ve spent any time on the internet delving through the Youtube archives of people telling you about things you’d never heard of that suck, chances are good you’ve run into the ouvre of Christian Replacement media I was raised in. you’ve seen attempts to make Christian musicals, you’ve seen the Christian animations, and you’ve probably even come across the Christian superhero stories. Which suck.

You’ll see this kind of media absolutely everywhere but only once you puncture into the social space of the Christian media sphere. There’s an actual suggestion when you’re inside it that you should buy this stuff and wear the branding because it’s a good way to get people to notice you, it’s a starter of conversations and it makes sure people recognise that you’re Christian, Not Ashamed, in your pursuit of the attention of the heathens, moving about in their space and being a better person than them. That is absolutely not what happens. What happens is you go to a youth camp and see everyone wearing the same general genre of t-shirt showing off Christian bands, Christian branding, Christian media franchises and that’s all. And some of it is pretty lazy – I mean, seriously, Jesus → Reese’s is as far as that idea got.

There’s a lot of this stuff, and I know I’ve spoken in the past about the absolutely awful band Bunch Of Believers – wait, I haven’t? I haven’t subjected you, my readers and friends to that particular flavour of garbage? Well, heck, I’m going to have to work on that. Anyway, the point is, this stuff exists and it’s almost always derivative and it’s extremely weak in its execution. Often anything that calls for a thoughtful interpretation or even something where there’s a clear, useful connection to existing media, it’s not taken. Heck, it’s sometimes missed so widely you can be left wondering if the people in question are trying at all.

There’s a lot of this stuff, and I know I’ve spoken in the past about the absolutely awful band Bunch Of Believers – wait, I haven’t? I haven’t subjected you, my readers and friends to that particular flavour of garbage? Well, heck, I’m going to have to work on that. Anyway, the point is, this stuff exists and it’s almost always derivative and it’s extremely weak in its execution. Often anything that calls for a thoughtful interpretation or even something where there’s a clear, useful connection to existing media, it’s not taken. Heck, it’s sometimes missed so widely you can be left wondering if the people in question are trying at all.

Which they’re not.

Know why this stuff is all garbage?

There are two basic reasons that the Christian Replacement Media is low quality. The first is it’s an industry; it wants to churn out things with as little effort as possible to scoop up as much purchasing power as it possibly can from the networked church system of industries, and it wants to do that as cost-effectively as possible. People aren’t buying clever or good, they’re buying in-group markers. The other reason, though, and it’s the reason that makes so many of those tv shows and the like look so bad is because they’re often aiming for an audience that has no idea about quality. They’re not dealing with audiences who have seen and tried a lot of things – they’re dealing with some audiences who have only really experienced the Christian media landscape, people who are dismissing non-Christian media out of hand, and people who are trying to insulate their family – usually children – from the harmful influence of Things That Exist.

These things exist to suck because they literally do not want you to have anything better to compare them to.

Game Pile: Sam & Max Episodes

I wanted to write about this game three weeks ago – but I felt I had to get perspective. I felt I had to really get into the roots of what I actually thought, what I actually felt about this game and why I wasn’t liking it. I wanted to resist the knee-jerk response of but it’s new, it’s not as good. I wanted, I really wanted, this small form delivery of adventure game content to be a good idea, and I wanted to hold it up, I hope, to people who might want to consume more of it, who might have been shy, as if The Walking Dead and The Wolf Among Us hadn’t already seized most critical attention and pulled eyes onto this form.

Still, I am a Sam & Max fan; I do love this franchise, such as it is. Or do I just love one particular game and a cartoon? Oh, these are the tangled spaces we find ourselves in as we indulge in fandom.

Ugh.

Still, let’s get it straight.

Continue Reading →Player Currency

Players play for something. There is an emotional reaction they are pursuing. Some players want to play with the cool toys and interactions of a game. Some want to play with the high-wire moments of excitement as they take a gamble and go for it. Some want to hear a story, some want to tell a story. Some players love that moment where they push a button and things all go wrong.

This is the concept of player currency – a way that a game can generate a way to buy player attention, a way to invest them. Many games can generate different varieties of currency all at once. Look into this, look at why people play, and listen to the things people use to describe the experiences they enjoy.

Everyone plays for a reason.

Project: Spook Street!

The Pitch: It’s a tiny deck-builder game about playing cute monster girls trying to decide if they want to spook houses or be cute at them.

Details

Every player starts with a small deck of cards, 4-5 large, which show your monster girl character making a variety of faces in her costume. There’s a grid of cards representing a neighbourhood, showing a door, and flipped over they show a number of candy cards to be distributed amongst the trick-or-treaters.

There’s a _plan file available for this, that you can read here.

The aim for this game is around 70 cards and a tuck box. Also, if it was being produced with a fast artist in the united states, it might be available to launch on Halloween (pfft, good luck for that). If not for this Halloween, maybe a future Halloween?

Needs

While I have a vision in mind for this game, with icons of a small group of monster girls pulling various cute or silly faces, I don’t have any art assets, and the variety involved would require a fairly coherent artist.While it’s one thing to want a bunch of face icons of cute girls pulling faces and having happy fun, it’s a lot of art assets, and not as simple as commissioning art of a character that can be reused.

Also, I cannot currently afford to actively commission this game project! I do not know if my state of money will change or how your relationship to the potential payment would work out! Do you think you have the skills for this? Are you interested in the idea? Feel free to contact me, either via the Twitter DMs or by emailing me!

Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug & Cat Noir, Pt 2. – Marinette

Here’s an idea, he says, missing PBS Idea Channel So Much Already, Miraculous is a superhero story of a different type because it is girly.

Don’t get at me on this one. We exist in a world with a culturally-accepted, defined and utilised gender binary, and all the Gender Is Fake, and Girly is Fake comments you can throw out there won’t change the fact that it’s part of how we do exist, and in that existing, there is definitely such a thing as girly stuff. And Miraculous Ladybug is very girly.

Girly is in this case a shorthand aesthetic for the things we already signpost as of or relating to girls. It’s in part an aesthetic, choices full of pinks, bright colours, pastels and broadly emotionally approachable signals. In a lot of media these are things that are also coded as being frivolous, or unimportant, or inherently comical. In Season 1 of Ladybug, Marinette is shown focusing on a fashion show, a school play, a babysitting job, and a literal popularity contest, which are all things I’m fairly sure Spider-Man has made fun of caring about.

They are serious though, and Marinette takes them seriously. Taking these things seriously involves looking – seriously – at why we don’t, about what about them makes them Not Serious. Why is babysitting silly? Why is fashion silly? What makes them somehow less worthy a subject for a teen superhero to care about than, say, a chemistry experiment or a baseball game?

Sexism, yes, but think about the specifics. Why shouldn’t these things matter? Why not? When you start to remember these things are competitions or challenges with their own stakes, and the story takes them seriously, they’re just as rich a vein of fodder for the story as anything else. Since they’re inherently low-stakes problems in universe, though, these aren’t spaces you can have things like Out of Control Lab Accidents that make people into monsters, or introduce gunshot-level threats. The problems in Miraculous have to be superhero-worthy while having roots in these very mundane activities we entrust to children, without the framing of being Eventually Important versions of Important Things that we normally code as for boys.

Know what definitely is a real thing that can feel worthy of a threat in those situations? Human emotions. Distress and sadness and anxiety and all these problems that we struggle with as adults, and maybe don’t even successfully handle. When you look at the problems that come up in the first season you have problems like being ignored by your parents when you were right, not being respected by your peers, being given conflicting information when you’re too young to understand it and being rejected and spurned by someone who you realise was much worse a person than you ever imagined. These emotional states are then, through the narrative tool of Hawkmoth (Papillon in the French, which makes me giggle), transformed into open, obvious metaphors for being stuck on that emotional problem.

There’s also how it informs the tension of the story’s protagonists: Adrien and Marinette are both characters who have Got It for each other, but this tension is not arbitary. Adrien is a good looking boy – both in universe, and also in his design. The story doesn’t present a Very Average looking boy as being handsome, and there are boys around him who are also less pretty, showing the story is actually making him exceptional. The boys are presented as needing to be visually interesting, and they are, rather than being more or less templates of one another.

When the time comes, however, that Marinette takes action – as Ladybug, mind you, since this is clearly part of her contention as a superhero – none of the negative traits we associate with Girly are a problem. Marinette is not shown being paralysed by emotions, or wrapped up in indecision. There is a confidence to her actions that typically would be coded as Not-Girly – but this is story that is so happily and wholly Girly it serves more to ask the question Why Would This Be Out of Type? Ladybug’s behaviour is unlike Marinette’s, but that’s because Marinette isn’t confident – not because she’s a girl.

Let’s take this one to a point of demonstration. In episode 6, the villain, Mr Pigeon, has a whistle that lets him control flocks of pigeons. Oh and spoilers I guess. Point is, in this episode, there’s a moment where three people lunge for it and their hands hit it in a stack – Cat Noir’s hand, then Mr Pigeon’s hand, then Marinette’s hand. And without thinking about it, without a moment of ‘ahah!’ or looking to the characters’ faces or whatever, bam, she just smashes downwards and breaks the object at the bottom of the stack.

Marinette’s problem-solving, the power of getting one Lucky solution in the right time and place, is really excellent as it shows her being thoughtful and confident, quick-thinking and decisive. The story will present her with Oven Mitts and say fix the problem, hero, and she will come up with the solution in some of the most wonderfully silly point-and-click adventure moments in media.

Miraculous is a girly superhero show. It’s about a girl, it’s about the things a girl cares about, and it wants to talk to girls in the storytelling tools of girls. And it’s absolutely great.

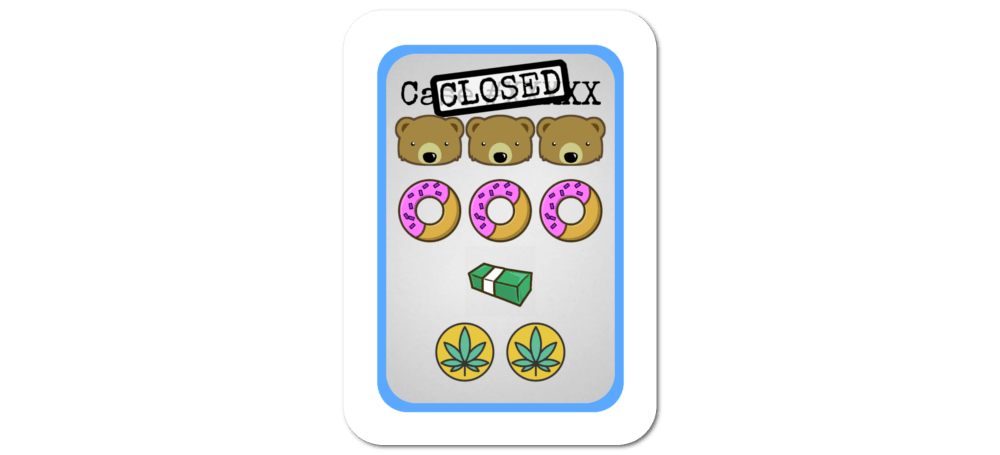

Working In Layers

Making card games in print-on-demand is mostly the task of making a large .pdf which shows every individual card, back-and-face, like a book. When I first started out – well, when I first started out, I let Fox do it, because it was super hard and I was embarassingly bothered by Scribus.

Scribus does suck, but I was more afraid of it than I should have been and that meant that I did as much work as I possibly could in some games like Murder Most Fowl, where while the card had a variable face, each was a whole image, crafted for each version of the card, then put manually into a file. This meant that that game’s file is very large and I was using graphical arts to handle layout stuff.

What’s that mean? Look, if you haven’t experienced it’s hard to explain, but it’s the difference between being able to easily move around bits of a design and replacing them quickly.

My first proper experiment in using Scribus to layer the components of a game was Good Cop, Bear Cop. Here’s an example card:

And here are the five layers that go into that card’s face.

What’s this mean? It means that if I do something redundant to a card I don’t need to edit twenty files in the .pdf – I can just replace the file showing that component and it works. This happened in Good Cop, Bear Cop: I was originally using these icons for two of the game elements:

Which I replaced with these:

Replacing these icons meant I edited three images that were otherwise transparent, then reloading Scribus.

MTG: Seasons Of Standard Bannings

Magic: The Gathering is a game with a long and storied history in a player base populated mostly by people who seem to be drawn to this game so they can tell other people how to do things better. During the history of Standard, there have been four major rounds of bannings, and, until this most recent I had this personal hypothesis about the impacts of these and what they told R&D about the way the game worked.

Round 0: THE DARK TIMES

I’m not going to lie to you, I barely understand early bannings. Things were the wild dang west. There was a format where ten cards from alpha, the original duals, were made legal, but only them. I don’t know this period well. Moving on.

Round 1: Combo Winter

Randy Buehler gives a fantastic rundown of the decks of this first great era of standard bannings, the time when Standard was A Thing long enough that bannings were themselves, A Thing. This period was known as Combo Winter, which was not the same thing as Black Summer or the Era Of Fruity Pebbles or the like. The impact of Urza’s Block and to a lesser extent, Tempest, on the various other formats like Extended was huge and all, but this is about Standard.

Standard having an era of Combo is noteworthy because combo is kind of one of the easiest things to develop against. Combo decks want to interact as minimally as possible, and if you can just have the time to grind through permutations or tested versions of decks you can head them off. You don’t make combo looking for your opponent to do a thing, you make combo looking for your opponent to not do things.

These three events, by the way, are compared to one another, but it needs to be said and re-said: None of the other eras were as bad as Combo Winter. Combo Winter was a period where you could actually lose on the first turn, or where you could functionally lose on the first turn. Combo Winter was when Wizards banned a card as an emergency. The closest we got to that ever since is when [mtg_card]Mind’s Desire[/mtg_card] was restricted in Vintage before it was ever legal.

Round 2: The Year Of Aggro

Fast forward to Onslaught-Legions-Scourge Mirrodin-Darksteel Standard for the next bannings. Then [mtg_card]Skullclamp[/mtg_card] got axed. Despite that, what followed along with that was a full year of Affinity aggro being the most widely played powerhouse deck in Standard. There’s some argument that Sarnia Affinity, a build popularised by Geordie Tait, was the best affinity deck pre-Darksteel, because it was basically a permission deck that just played double-lands until it could vomit a [mtg_card]Broodstar [/mtg_card] into your face, but it didn’t matter too much because Affinity aggro decks were good enough that ‘best’ was meaningless. Best builds of Affinity were negotiating winning the game on turn 2.3 as opposed to 2.4, so it didn’t really matter who was ‘best.’

This period is notable because Onslaught Goblins were also running around so you couldn’t even double down hard on your Affinity strategy. Kamigawa wasn’t going to help any either, because by that point the game had bled a lot of player base. Affinity decks were made mostly of commons and extremely expensive rares, meaning they weren’t a bad place to jump into this very awful tournament format, too! Affinity had power but it also had reach, and flexibility and resilience.

Aggro is harder to balance for than combo. It wants to interact. Blockers can gum up the ground. It fails to mass removal without resilience. It’s harder to be sure you haven’t done something like this.

Weirdly, Wizards have actually printed a bunch of much stronger creatures than were being printed back then, and relaxed on global control – but the relaxation of global control has made it so aggro decks are a little more prone to have to deal with blockers, and therefore, aggro decks don’t have to be so utterly cutthroat as they did back then to deal with things like [mtg_card]Astral Slide[/mtg_card].

Round 3: Control Summer

Cawblade is an interesting thing it is was the first truly oppressive control singular deck that deformed a standard environment. When there were 4-5 permission decks that could shut the game down and keep the environment miserable for all the things people tended to want to do, single decks like that didn’t stand out.

The issue of Cawblade wasn’t instantaneous loss of power. It wasn’t that it was capable of snapping the game out without you ever having a chance to do anything: It was that it was a control deck that could play like a prison, that could just answer everything, that was so powerful and had so many good options for answering anything.

Cawblade was not a deck that won fast. It was just a deck that didn’t lose and took forever to do it. And as a control deck, it was the hardest to hit with bannings.

Round 4: Today

Hey, Standard’s been weird hasn’t it! It’s had a bunch of bannings! But at the same time, the bannings have been about disabling a number of decks, which is pretty weird. Particularly, [mtg_card]Smuggler’s Copter[/mtg_card] was the most obvious one – it was nuked just for being everywhere and going in every deck.

I’m not going to restate things Wizards have said about these rounds of bannings. They’ve been in aid of diversity of the format, of making some cards good enough to play, but most interestingly to me, the decks they’ve hit have been mostly different types. There’s been a combo deck, a control deck with a potentially explosive win condition, a midrange tribal deck, and a control powerhouse finisher that was being played in a lot of decks.

None of these are good things to have to hit. Standard got bannings because Standard had problems.

But oh my god they are problems of a totally different scale as the ones in the past.

The Lesson

This represents an interesting set of ways to view balance, to view ways of balancing. First, make sure no player can do too much on their own. Then, make sure player interactions don’t pressure players into the fastest iteration, and your design isn’t being pushed to force players to go too fast for there to be any meaningful responses. Then, ensure that the game isn’t built to allow for too many useful responses, solutions to problems.

Shirt Highlight: HUIZINGA!

If you’re like me, you probably hate The Big Bang Theory, and you probably hate it even more when someone references it to you as if you should understand it. Yes, I study or read criticism, or trust science exists, that definitely means I am inclined to the comedic ouvre of one Chuck Lorre. This is our common ground, random stranger, this is the footing on which you and I can build an understanding, a friendship, and perhaps one day, love, blossoming into our lives and binding us together until the shadowy eternities close on us all and I hold your hand while one of us slips away first, murmuring, yes, it was definitely better than Young Sheldon. You sure get me and people like me.

However, if you are like me – and almost painfully specifically like me – you’re deeply amused by the comparison between Huizinga and Bazinga, and the imagery of the Magic Circle. And then, if that’s you? Well, this shirt is totally for you.

Steve.

Game Pile: Nuclear Throne

With Sam and Max Hit The Road tucked away, I have to take a quick detour to describe a very different game, a game that is, nonetheless, very important to talking about the point-and-click adventure game, and more importantly, which provides useful context for its sequel episodes. But don’t worry, because the game we’re talking about here is Vlambeer’s Nuclear Throne, which is super great and I love it to bits because it’s super great, so this won’t take long.

Invisible Jellyfish

I really like Cave Story. It’s one of my favourite games. It’s a great little platformer with some exploration elements to it. For a while there I thought of it as Metroid like because it used exploration as a mechanic – mostly you spent time looking around for things to take you forward. Some further thought has me wondering if I’m just mistaking something important about the game, and what got me wondering about it was the Invisible Jellyfish of Chaco’s House.

In Cave Story there comes a part of the game where you, on the way to somewhere, hit a door and a wall. Through the door, there’s a bunny named Chaco, who will tell you that to go onward, you need the juice of a jellyfish that’s back the way you came. If you’re like me you thought: What jellyfish? I didn’t pass any jellyfish. Maybe there’s a hidden thing back there I missed that the game now wants me to go back and look at.

Nope! You turn around and head back and now the space you were in is full of jellyfish!

Now, playwise this is a lot of fun! You’re now being conditioned to handle the area you just moved through in reverse, except now it has different things in it and needs different stuff and that’s super cool! It’s not a bad moment! But when you look at it, it made me wonder if exploration is really the thing that Cave Story was about.

Then I thought more about it and… largely, Cave Story is a pretty linear game but it has a nonlinear story. There are some diversions, some cul-de-sacs, some small things you can do on the way, and some priorities you can finish in other order, but the routes of the game always meet up at the same point. You still have to do most of the game’s events in the same a-b-c sequence, and you find them by moving away from the last thing towards the next thing.

Still love the game, but I was thinking about it wrong.

Bad Balance: Your Part In Failure

Dungeons and Dragons 3.5 was absolute nonsense balance-wise, but it was remarkable because it was imbalanced in a whole variety of different ways that are good object lessons for designers to take on board when making your own RPG content. So, rather than one huge master-post explaining it, here’s one example:

Your Failure

You’ll find if you listen to any given D&D 3.5 player, they’ll usually have some memories of the things I talk about being total bupkis. I know I played alongside a cleric who wasn’t overpowered, and we had one game where the runaway behemoth was a telepath. As your friendly neighborhood min-maxer I had the game squealing under the heel of a bard, once. More often than anything else we’d see on the newsgroups players wondering about how they could play clerics well, because they thought their only job was standing by and healing, leading to an unfulfilling game of whack-a-mole. What’s more there are a lot of games where the wizard player felt worthless and ran away from goblins a lot with a terrible armour class. Once I heard the artificer dismissed as trash because a player could simply not imagine how to make it work.

This is one of the many ways D&D3.5 was unbalanced: It was entirely possible to play overpowered characters badly. Most of the characters who were busted were busted because of spells or magic items and that stuff was overwhelmingly available…

If you took it.

You could absolutely play a weak wizard! You could pick up the twenty totally worthless spells at every level, you could sink into the swamp of crap. You could take a level of sorcerer and a level of wizard, and then maybe level them up side by side and maybe you’d balance your stats and oh good god noooo.

You could be handed a high-octane chainsaw laser hammer and it was entirely reasonable for a new player, a player who had no reason to expect they were being given something totally broken, to sit down and tap nails in with the wrong end.

Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug & Cat Noir, Pt 1. – The Gush

Holy crap oh my goodness this show is so good people. I’d normally like, try and structure this whole thing somewhat and there will be time for that but for now, I’m just going to gush about some things in this series I really hecking like.

Here’s a thing! Ladybugs are a symbol of luck. I didn’t know that going in, and for a little while I was confused as to why they chose the two characters they had – the black cat and the ladybug and I just didn’t quite get why. Then when you find that ladybugs are good luck, the imagery and meme of the black cat as bad luck and – and that’s good use of imagery and concept space! That gives you space to look at the two characters, gives you a nice, simple place to start from! It anchors characters to existing media spaces and it gives them distinct, interesting visual theming!

Here’s a thing! Ladybugs are a symbol of luck. I didn’t know that going in, and for a little while I was confused as to why they chose the two characters they had – the black cat and the ladybug and I just didn’t quite get why. Then when you find that ladybugs are good luck, the imagery and meme of the black cat as bad luck and – and that’s good use of imagery and concept space! That gives you space to look at the two characters, gives you a nice, simple place to start from! It anchors characters to existing media spaces and it gives them distinct, interesting visual theming!

That means that when they work together in the same space, despite the fact the two characters are basically the same style of fighter, and move more or less the same way you’re never left confused as to which one you’re seeing in a moment of action because one is bright honking red and the other is black, but neither of their costumes seem to be of a different type to the other!

Also if luck is the thing that defines the two characters it means your solutions to problems can be extremely outlandish or one-time! A character who relies on luck as a theme means that if she only gets a thing to work once that’s enough, unlike characters like Batman who rely on being heavily prepared! This means things can be both more thematically interesting and varied while also showing off the character’s quick wits!

Oh and the enemies! All the enemies are empowered by the real villain when they demonstrate a moment of emotional distress that the can’t handle or process properly – which is to say, this is a series where the big conflict point is processing your emotions properly. Nobody’s sadness or anger is shown as being illegitimate, and nobody’s emotions are used to excuse or justify the things they do – because the villain is using magical powers to take control of them, there’s no need to do that.

This is great because it means you can treat emotional duress as important and worth respecting, you can show characters repeatedly resisting it or engaging with it to show their growth as people, and you can even show how some people’s processing can be inhibited or expressed. Then you get the added dimension that both adults and children fall prey to this power set, for a variety of different reasons – some are meanspirited and cruel, but many of them are frustrated or misunderstood! This means there are stories about handling emotions as a child and as an adult and at no point does the story just say ‘well suck it up.’

So you have these characters who are directly expressing rudimentary metaphors about emotional processing in a way that involves actual cool looking fights with some dynamic, interestingly chosen characters who fight and think and are cool at things, and then the aftermath is about watching the protagonists grow in light of the things they now understand about the emotional process their friends went through, and there’s no guilt or rancor about the times they were turned. There is a legitimate recognition that someone else preyed on their emotional state and ‘made’ them into villains, and that those moments of distress or anger or rage don’t represent who they truly are!

This is romantic storytelling at its most primal, not romance-as-interaction, where people are smoochin’ and doin’ smooches and that’s all the stories are moving about, but romance where human emotion are the driving forces of the universe, where the story is always moving in ways to make human emotion run against other human emotion! Coincidence transpires – and it’s fine, because the story isn’t about the realism of events – and then that brings people’s emotions to bear against one another!

Things don’t need explaining, they need understanding.

Plus it’s funny. It’s funny in a way that doesn’t treat its viewers – who are kids – like idiots. It doesn’t pitch its comedy low, and that means it projects a sense of respect for its viewers. They show things only a few moments, and don’t need to over-explain it – basically it’s like an exact, functional opposite to Suicide Squad, which overstates everything and is also grim and dark and grungy for no good reason.

I have more, but I kind of want to save more in-depth conversation about it until I’ve rewatched some of it, but also to do a bit more of an in-depth read on Marinette as a character and what choosing her has done for this series as a superhero story.

God it’s a good time to like superheroes.

Innovelty

Recently, I was listening to the Ding and Dent podcast which decided to take a momentary sidetrack into the idea of innovation as its importance to games, and it got me angry enough to sit there and froth at my computer for a little bit and write a very angry, very foolish draft.

Fortunately ‘recently’ means mid August because I try to write ahead on this blog these days, and that meant I had time to cool down and relax on the stance and come back to it to talk about my problem with the position.

So here’s the thing with innovation. For something to be innovative, it needs to be, in contrast to other examples in its type, different in a new way to overcome a challenge. The problem with describing things as innovative is that it inherently positions the speaker as an authority on what is a meaningful contrast.

The thing most people mean when they say innovative is novelty. They mean this does something in a way I hadn’t considered. Why does this give me a bee in my bonnet, though?

Because games are so broad, so wide, happening across so many languages and so many markets right now, the idea that any given thing is innovative means that the games that the speaker understands must be the ‘normal’ that exists. That a reviewer – usually of big box board games from four or five publishers – has a lens that encompasses all the games that are worth considering and therefore, what is new to them in that space is innovative.

This is an important thing to consider!

I prefer instead to talk about novelty – which is to say, this is news to me – because it avoids unintentionally positioning the speaker as an authority, and it helps push back against the idea that the small core of games being examined by reviewers are the general landscape of games.

MTG – Balancing Beatsticks

Magic The Gathering is what we in the dank academia call a ludic game1.. There’s not a lot of room for entirely non-system play, not a lot of room to give things an individually boundless creativity. There’s some creativity in deck building, but it’s not boundless. You have to put in the cards that already exist, for example, and those cards have to be put in with some limitations and to work, they need to be put in in certain proportions and you wind up being fed into a system.

This isn’t a criticism, by the way. Just a basic analysis. This is just something of how the game works.

During spoiler season we saw [mtg_card]Sky Terror[/mtg_card] printed. There was some concern about how pushed that was, about if that was too much for 2 mana, and there was some talk about its impact in limited. It’s actually super interesting to me, to learn how gold cards shape your early picks – it’s the difference between 3 slots and 11 slots in your mana base, I learned.

Anyway, this prompted something of a conversation about how powerful this card was, while a certain body of people, myself included, responded with… big deal. It’s a flier and it has menace. From that, I wrote – mostly – the following explanation.

In Magic, not all evasion abilities are equal. In fact, some evasion abilities, when they start to interact with one another, are pretty weirdly weak. Sometimes this is obvious, like giving a creature with flying reach, or giving a creature with fear intimidate. On the other hand, sometimes it’s a little subtler. Lemme tell you about Coldsnap.

Back in Coldsnap, there was this card, [mtg_card]Phobian Phantasm[/mtg_card], which was a FEAR FLIER. It cost 3 for a 3/3 and it had cumulative upkeep and people thought it would be really strong, because it’d be able to fly and not be blocked and it hit for 3. This was the first impression of myself and others2..

The problem is, fear means nothing on a creature that already flies. Most fliers aren’t getting blocked anyway, because the things that can block it are your opponents’ fliers and most of them don’t want to block because they are also turning sideways. When it comes to the way constructed works out, evasive creatures rarely get involved in creature combat, because they don’t tend to have a lot of varieties of bodies, and combat tricks aren’t commonly played (because they’re not so valuable when people rarely get into combat!). You can usually look at evasive creatures and know whether or not they’re going to get blocked at all. Now, this isn’t always true; sometimes a format will feature something that can gum up the air like say, [mtg_card]Hornet Queen[/mtg_card], but that’s not the norm.

The reason you tend to kill these creatures by combat in limited, of course, is because you don’t have reliable access to removal, and the removal you have is sometimes truly terribad. R&D have almost made a game of designing bad removal spells just to see who still runs them, and boy, turns out they still do.

The thing with this card looking so pushed (and it is pushed, by the way, just not in the scary way it may seem), is that we’re very much conditioned to think of cards as being generally made as a formulation; that every card is about as good as that card can be. This is something that drove me batty until I internalised it whenever Wizards printed a 4/4 for 5, like say, [mtg_card]Game-Trail Changeling [/mtg_card].

A menace flier may look impressive but it’s not going to get blocked anyway. In constructed, it’ll get abraded or shocked or pulsed or planked or whatever, because that’s what spot removal is for – wiping out individual things that are trying to carry the game, and a 2/2 creature needs to live for four or five turns to make a big difference on its own. It’s why constructed creatures tend to either be capable of swarming out cheaply, rebuilding after a clean-up, or closing the game on their own in a few short hits. You’ll notice rarely do people bother with 7/Xs in constructed if they can get a 6/X that does the same job cheaper, or a 5/X, because the only real virtue the 7/x has is punching through 7-toughness blockers… which are also suitably rare.

This is one of the magic tricks of design; for most intents and purposes, a number of creatures have invisible or meaningless text on them that still makes them feel interesting, still changes the nature of the game while they’re being played, and it’s very interesting seeing the way they influence the game.

1. The alternative term that’s meant to represent games with more individually creative elements is paidic, by the way.

2. I at least kept my reservations about the card because I hated fear and thought it was bad design.3.

3. A thought that was totally vindicated, mind you.

Perry’s Lock

Hey, I can use this blog for any old bullheck I like, why not use it for this.

I ran this D&D campaign called All The King’s Men, when I was a younger man with different pets and worse hair. The premise of the game was that in the great City-State Coalition of the Symeiran Empire, there were three orders of church knights, each compliant with one of the three law-chaos alignment axes. Lawful knights, neutral knights, chaotic knights. In this party of six, three players were knights, and three of the other players were the direct contact and friend of one of the knights. Three adventuring pairs.

The lawful knight of this group, Kyrie, had her offsider, a luvable cawkney thief called Perry, short for Peregrine. Perry was chipper and playful and had a luverly accent and Perry was great. I loved Perry to bits. Great dynamic with the other players, and also, the player is a great min-maxer. Now this is 3.5 D&D with a lot of homebrew content, alongside people who love to optimise buuuut aren’t as good at it as Perry’s player was. Perry, rather than be a dick about it, therefore dedicated himself to find the things nobody in the party did and do it excellently.

In the first major arc of the campaign, a door was locked before them, and the party were losing time chasing the person who’d locked it behind them. Perry then popped his knuckles and said hold my beer, before sitting down and cracking that lock with a truly grotesque skill check in the fifties. Bear in mind this was at level six or so! He pops this DC 15 lock with a skill check enough to do it as a free action, stepped through, and once the party were in, locked it behind him to keep others from pursuing.

Okay.

Fast forward a year and change and eleven levels, and the party have returned to this same site, to find it taken over by vampire nobility. The familiar zone they ran through at a dead run, chasing someone was now a sieged path they had to work through, a dungeon crawl, full of decadence and dangerous vampires. The party stopped at a door, and Perry, who by now is basically a Time Ninja or something, looked at it and said ‘well, I’ll check it.’

‘It’s locked.’

‘Oh, okay, like a magical lock?’

‘Not far as you can tell.’

‘Okay, I’ll just Open Locks on it-‘

‘Roll.’

‘I have a huge bonus, seriously?’

‘Yeah, there’s a chance you can fail.’

Perry’s player gives me a look, as he picks up his d20 and rolls poorly. A fairly low roll – a 4 or so. But he’s been so good at things so far that he’s convinced there’s no mundane lock that can actually impede him. A moment, – ‘Forty eight.’ I check the notes and…

‘Nope.’

‘What?!’

‘I said nope.’

‘Who the fuck locked this door?‘

‘YOU DID.‘

(He took ten and got the lock just fine, if you were worried.)

Game Pile: Sam & Max Hit The Road

Okay, so straight up, Sam and Max Hit The Road is one of my favourite games. It’s a point-and-click adventure game with some frustratingly obtuse puzzles. I don’t know if I can even recommend it as a game per se because the times I struggled with the solutions to its ridiculously obtuse view of the world are all so far in the past that I can’t imagine how anyone would solve them. Some of the puzzle solutions are positively arcane.

When you boil down a lot of point-and-click adventure games, they have one problem: Use key on door. In fact, sometimes games that tried to do something different (like Future War and Full Throttle) were criticised for the involvement of those other elements. In Sam and Max Hit The Road, there’s a handful of, y’know, bits and stuff designed to introduce other puzzles and problems, but none of the game is too hard once you grasp the thread of the game’s weird poke-it-and-see methodology.

So, right, as a game: It’s good, but it’s of its time. The GOG release brings automatic saves and windowed play and those are nice modern conveniences. Okay? Play it with a walkthrough nearby but don’t follow the walkthrough directly. Just use it when you’ve poked everything to laugh at the responses you find, but not to remain stranded in a narrative point for a while. I like it, I think it’s good, it’s cheap and it’s really funny.

And hey.

Now.

Let’s do the heck out of talking about Sam and Max Hit The Road.

Continue Reading →Bad Balance: Free Power

Dungeons and Dragons 3.5 was absolute nonsense balance-wise, but it was remarkable because it was imbalanced in a whole variety of different ways that are good object lessons. So, rather than one huge master-post explaining it, here’s one example:

Free Power!

A thing you’ll find in most games is there’s an opportunity cost to adding things to your character. Magic items occupy this space in D&D where there are slots, clearly recognising that there’s a good reason to limit the number of belts you wear, especially when those belts do magical things. Thing is, the item system isn’t the only place that came up.

In most games there’s an opportunity cost. Every choice you make is an option. In 3.5 D&D there were a surprising number of times when there were no such choices. If you were aiming for a prestige class at level 6 onwards, your first five levels could sometimes look like utter nonsense – fighter 2, barbarian 2, ranger 1, for example, would give you a grotesque fort save, a handful of benefits and lose you a single point of reflex and will, which was just not a reasonable trade. If you were building a wizard, prestige classes themselves could look ridiculous, as you cherry-picked the opening benefits of four or five of them because none of them had a meaningful late game reward.

When you give players an option for something, you need to make it so that they’re giving something up if they take it. Not that every option is punishing – that’s its own bad idea – but that every option is a choice, and choices should be meaningful.

Making Notes: Who Makes My Tokens?

I have this game idea: It’s a worker placement game where you’re overseeing a heist on a casino while other gangs are trying to do the same thing. There are a few ideas I like here, where the board is made up of a set of cards, which means it changes from game to game, and where and how you get to the locations for placement are in turn influenced by the movement of security guards between the cards.

What this game wants is a small number of cards: Right now it’s as few as fourteen possible cards to make a 9-card grid. It wants to have space between them, the cards have suits and behave a bit like poker hands, whatever. The point is, that it’s a small number of cards, but it needs ways to mark where you, the player, have put your workers.

Also, the workers have hidden information.

Now normally if you have something with hidden information, you use something with two faces: A card, duh, right? The problem is that putting a card on a card obscures a lot of that card’s information – and you need that information to make decisions about where things are. Moving other players’ cards might accidentally reveal things and it’d be a lot easier to put/move smaller tokens around.

Simply: This game wants tokens. Heck, this right here is nonsense, really: I should be in a position to say this design uses tokens without having to justify it!

I do most of my printing of card games through DriveThruCards. They are not a perfect printer service. I don’t know what a perfect service would look like – though I guess they’d be much more local and I wouldn’t have to pay international shipping and wait three weeks for my product to arrive for when I wanted to sell it face-to-face. That sucks (for me).

Still, I like DriveThruCards. The staff are nice and they’ve been very helpful with problems we have. I’m familiar with the tools and they have all my games on catalogue (with one exception). They work. There are, however, things th at they don’t do. In this case, what I’m thinking about is tokens.

The place I normally use for tokens is GameCrafter, where we made Skulk. It’s a good place for its kind of work, but if I put it there I need to do bulk orders of hundreds of games, and with only one game at a time there, I simply can’t afford it. The best sales I get are in person, where I can show a person my game and watch them buy it.

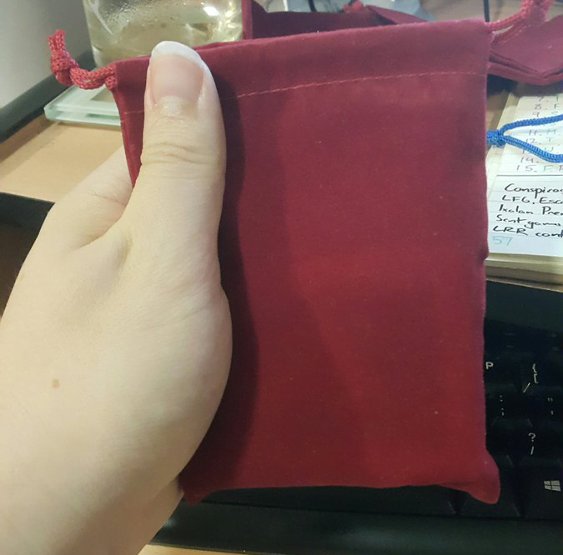

That means the sites are not worthwhile as markets, but rather as production fronts. It’s ridiculous. On the other hand, their tokens are really good: I like them a lot. One idea is to make the whole game there, and instead of buying a box, putting the game in a single nice bag like this:

This bag is about 5 by 4 inches; it’s light, it’s soft. It also, crucially, does not sit on a bookshelf neatly, and that’s something that Fox doesn’t like, and I also am sympathetic to that position. Still, there’s a definite appeal to a bag with some tokens and some cards that unpacks into a bigger, complicated game with a euro-game style thinking-building play style. It’d be affordable too – somewhere around $15-$20, which puts it around the level of our mid-cost card games.

I like our tuck boxes, which are standardised sizes, all cardboard, recycleable and give me room to put more designs and information. I like our tucks. The problem with the tucks is that they’re made at DriveThru. DriveThru gives me tuckboxes and bulk ordering and … no tokens. Now, I’ve done some testing! I can fit this game and all its tokens into the box quite easily, though then we meet a new problem: DriveThru doesn’t offer tokens.

There is a solution, one I’ve used for Wobbegong-12: That game comes with a card you cut into pieces to make tokens, and they live in the box you keep the game in. That would work, except there we have two new problems! First, the pieces would be cut up by end users, which mean that keeping tokens the exact same size and therefore, avoid giving away information to other players is hard, and second, there are some players resistant to the idea of cutting up cards. Bonus, I don’t know if those players are people who buy or want to buy our stuff, so… that’s hard to know how to judge.

There is a solution, one I’ve used for Wobbegong-12: That game comes with a card you cut into pieces to make tokens, and they live in the box you keep the game in. That would work, except there we have two new problems! First, the pieces would be cut up by end users, which mean that keeping tokens the exact same size and therefore, avoid giving away information to other players is hard, and second, there are some players resistant to the idea of cutting up cards. Bonus, I don’t know if those players are people who buy or want to buy our stuff, so… that’s hard to know how to judge.

This is a real pickle for me. This is also really frustrating because I like this game idea and I’d like to keep working on it. What complicates this further is that I can’t really get a good, useful response on how to approach this problem. Part of this is because there are people who would never buy this game who would still have opinions on how it ‘should’ work, and people who don’t know what the game is trying to do with equally firm opinions!

This is a really tricky place to be. It might just get the idea put on the shelf again, which would bum me out because I really like the idea. If Gamecrafter had a vibrant community, or wasn’t so expensive to ship around, I might try it out; if DriveThru did simple cut tokens, that would be perfect. Yet, neither are true, and so here I am, stuck with my tuck and my tokens.

This is the kind of thing you need to take into account when looking into your making process. How do you get your stock? Do you want stock? Do you just want to get access to tangible copies of what you’ve made? Can you split your sources? Can you afford to split your sources?

Marvel’s The Defenders

The Defenders is an adequate average of the sum of its parts. At its best it is Luke Cage’s snappy dialogue and Daredevil’s fight choreography in tight, threatening situations with an appreciation of highlight moments, and at its worst, it has Jessica Jones and Danny Rand in it.

Kind-of-spoilers below the fold.

Telling A Story Through A Game Pt. 2

Here’s a link to the first part. I said I had to go to the tank for this one, and boy didn’t I.

When you want to design a game that conveys a narrative without writing that narrative, and when you accept that all games tell stories, you’re left with a need to construct your game’s components so that they’re made up of potential events, or perhaps better expressed, you’re made up of story components.

One of the things that games tend to have that works well for them is the start of the game, the engagement of the player, is a singular instigatory action; the players’ presence change the status quo of the game’s universe before the player arrived. Now, most of the time the game’s narrative doesn’t incorporate that – most games tend to start from a place where nobody has done anything yet, and the game follows that.

That’s sort of all you need: You need the game’s mechanics to represent the movements, actions or reactions of people. People is a nebulous term, by the way: humans will see people in everything around them. It’s actually really hard to keep people from attaching humanity to the things in the games they play – how often do you see people treat the dice like they have motivation?

The trick then comes in making sure that players can all see the same things as having some degree of personality, of agency to them, something that forms the story around them. And to show the example of how this works, we’re going to look at two great games, with similar mechanics and a complete disconnect between the nature of how they tell story.

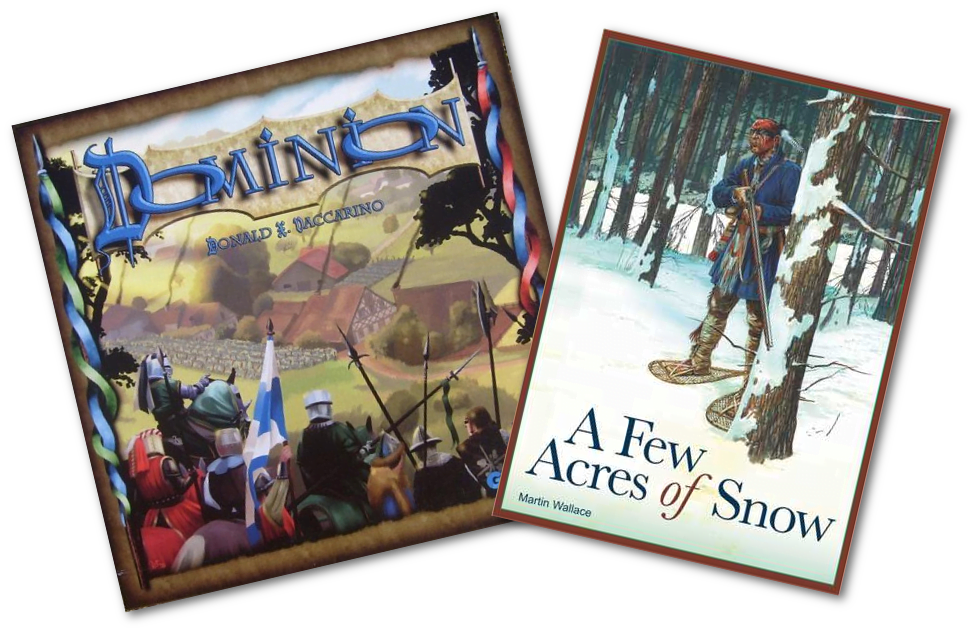

First we have Dominion, the game I tease as being themeless, and A Few Acres of Snow, a game about the invasion of Canada by America in that war they don’t like to talk about. Both games are deck builders, and both games have some pretty simple mechanics that they then expand outwards.

In Dominion…

In Dominion cards are bought from a grid, and there’s a sort of variance in what the cards are, with a very vague idea that you are a ruler, or maybe you are the territory itself, with your deck representing things that exist on your territory.

In Dominion, you add cards to your deck, which then take some time to cycle around into hand. There are cards that represent territory, which is how you achieve victory, there are cards that represent money, which is how you buy cards, and then there are all the other cards that lend some character to your deck.

The thing with totally abstract currency in your deck is that they represent … something. Something maybe. Sometimes, it represents people who work in the territory – silversmiths and blacksmiths. Sometimes it represents objects in your territory – like a moat (even a moat!). Sometimes it represents an object (the throne).

None of these are bad game entities, but when you lay them out, there’s no clear idea for what they all are. Are you building a throne? What do you mean when you have two thrones? Does a blacksmith turning a metal coin into a different metal coin represent something like an actual act of alchemy? There’s no clear explanation, no solid or robust theming. The game has a theme alright, an overtone – it’s one of a sort-of-medieval sort-of-fantasy kingdom, with something like a government, but that’s all.

In A Few Acres Of Snow…

In Acres, the cards represent the actions you as a ruler of the war can take, the actions you can engage with and the ways you can direct troops with a limited range of options – sometimes supplies just don’t show up when you need them, sometimes you have the chance to communicate with three or four cities and don’t have the supplies to direct to them. The mechanisms of that game put the player in the narrative position of a leader dealing with the constraints of a military movement during a time before instant-speed communication.

What this means is that the mechanics of the game become part of the story the game tells you: You’re a leader, you’re making choices, they are all based on communication, and the cards that represent people are people dealing with you and talking to you, people available to you within your limited sphere of communication. One of the best cards in the game for this is the governor – a character that when you buy it, comes into your deck, gets rid of two cards you don’t need any more… and then remains there until you get rid of them with another governor – meaning that over time you can have a deck full of governors, managing beaurocracy, meaning your personal communication is now clogged with fewer bad options but with more dealing with beaurocracy.

Soooo?

The difference between these two games telling stories is that the games’ mechanics require you to change your mental position on what the card entities are pulling your focus to. In Acres, the cards represent opportunities presented to the player, to you. In Dominion, the cards represent things within the player’s space. That’s what keeps Dominion from telling its story; the character cannot be the player, the centerpiece cannot be a thing on the cards.

So, when you want to tell a story through mechanics alone, you need to give the player a through-line they can observe. You need to give them something that can hold the story.

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @Fugiman on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!

MTG: The Anti-Legions

Hello, Wizards employees! I understand that you’re not supposed to see unsolicited card designs or conversations about same, and with that in mind I’m going to ask you to head elsewhere. Like to this rad interview with Alison Lurhs about Tumblr and MTG. As for the rest of you, let’s talk about making an Anti-Legions.

Man, that’s frustrating. I can’t help but feel this kind of article – if it’s good – would be great to show as a portfolio of design work. Ah well.

Continue Reading →

Arresting Godzilla

King of Tokyo is a great little game. I like seeing an existing simple mechanic used as a structure. I love mechanics as metaphor. I really like the metaphor it uses, the big smashy monster genre of movies. I like how silly it is, how it uses the tropes of that genre. I really like how the game makes for fast turns. Don’t think for a minute this is a complaint that makes King of Tokyo a bad game.

But.

It does have one awkward design thing, a little bit, a tiny thing that bugs me. It’s a thing that I feel like you can design around, but I’m not sure what the fix, what the solution would look like.

When you play King of Tokyo, enemy turns don’t have any inherent value to you. You do things on your turn, but unless an enemy attacks you (in specific circumstance) or they buy a card you wanted (which can happen), you and your opponents aren’t acting and reacting in ways that necessarily mean a lot to you. That means turns that aren’t yours are spent not paying too much attention. Normally, this kind of time lets a player make a plan, prepare for their turn to act quickly.

Except in King of Tokyo, you don’t know what you can do until your turn. No plan survives their interface with the dice. Which means you’re waiting, maybe planning, maybe even daydreaming, before you suddenly have the dice in your hand and bam, and suddenly you have to make a plan out of that.

I wish that the game either meant there was less time waiting for those dice, or there was more you could do while you waited. As it is there’s a sort of mental arrest moment.

Me, I don’t know the solution.

Game Pile: Dishonored: Death of the Outsider

I’ve commented on Dishonored, both entries of its DLC, and its Sequel in the past. It’s a franchise I’m comfortable calling one of my favourites. Now, here we are, at the final entry for this place, a final journey to the Kaldwin Era of Dunwall, and it is with joy and sadness, I return once more, to get to the root cause of all this chaos anew…

Continue Reading →Donald Duck, The Dork Deputy Dad