MTG: Dinosaur 2: The Nitpicking

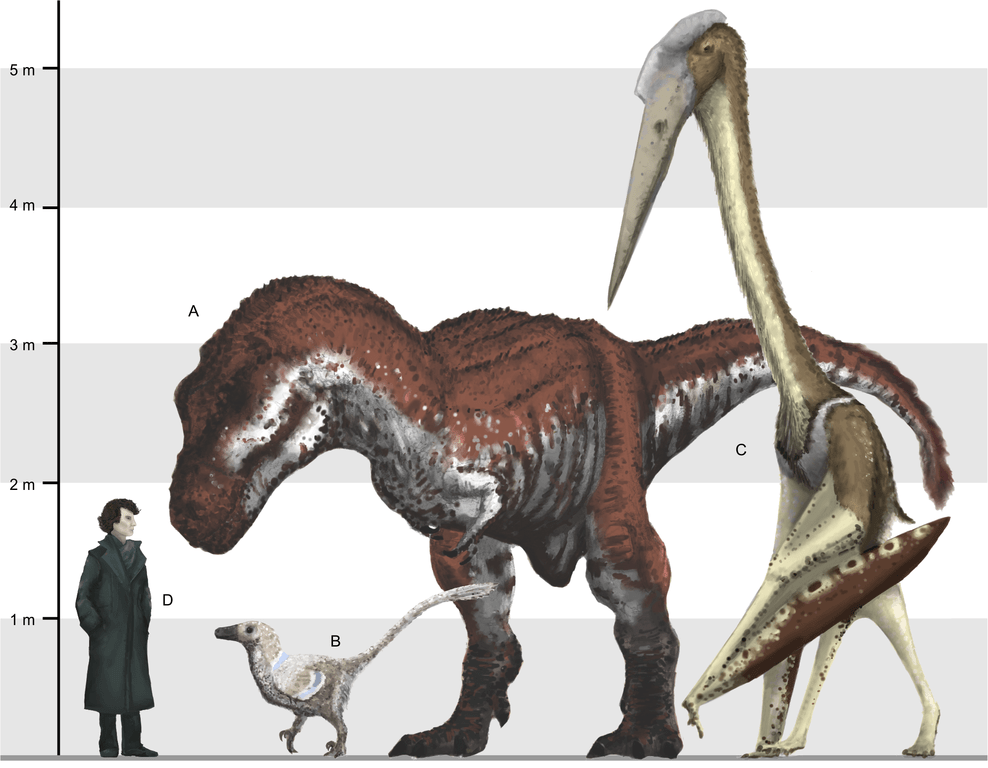

If you’ve been following my work for a long while (why), you might wonder what I think of the recent news that Ixalan will features Dinosaurs as a major tribe. I wrote about this in the past, where I came down pretty simply on the idea that Dinosaurs shouldn’t be creature type – Lizard or – Beast, and changing things would be a change for the better, mostly arguing from the perspective of the game as an educational tool.

Part of the introduction of Ixalan’s tribes, then, is that the set will feature dinosaurs as a distinct tribe, with their own visual hallmarks, their own mechanics, and notably, a unified, coherent creature type that can even be back-fit onto some older creatures that Aren’t Dinosaurs But Should Be. Maybe we’ll see Imperiosaur and Pygmy Allosaurus join the club. I’m pretty excited by this, but.

but but but.

There is still one last part of this needle to thread and we’ll do it, after the fold, because this will feature a spoooillllerrr for Ixalan. Don’t look! Avert your eyes, ye unspoiled!

Let’s Dismantle: Hocus

Hocus is a small-box card game made by Joshua Buergel and Grant Rodiek, with art by John Arios, Adam P. McIver and Tiffany Turrill, published by Hyperbole games, available here. As of the last reading of this, the game is out of print – it’s possibly changed, but right now it seems that the last copies of Hocus are being sold. If you live outside of America it can be hard to get because, I don’t know, we’re not worth the time. So far, So BoardgameGeek Summary.

Something I need to make clear: I have not yet been able to play Hocus. I really want to, it’s a lovely little game, but getting the people together to play something small is really tricky.

Also, this isn’t a review of a game, but rather breakdown study, taking the game’s components and examining them as a designer, to see what ideas they present, what lessons I can learn, and maybe you can use them too. Every game you play or examine becomes part of your library of possible things you can do with your own games, after all! This is not an analysis of play but an examination of the components of Hocus and, in part, a study of what you can do in similarly sized design spaces.

I’m going to have to say this up front because otherwise I’ll repeat myself throughout this: The components and art of Hocus are lovely quality. The box is robust, thick and stout, the cards fit in it snugly but not so snugly they’re a pain to get in, and the art is vibrant, beautiful and pops. The font choice is clear, everything has good margins, and there’s clear gutters on things. Simply put, Hocus is one of the best-looking card games I own, and I’m including my Magic: The Gathering cards in that.

Also in this, you might observe art-resource wise, there’s actually a bit less art than you’d think: there are four full-card art faces, about twenty different icons, and about five card faces and three card backs. Compare this to, say, a 100 card Magic: The Gatherin set which can have something like 12 faces, each with individualised art and one single card back.

What we have here is the total content of the box. Two decks of cards, a handful of guide cards,and some score tracker cards.

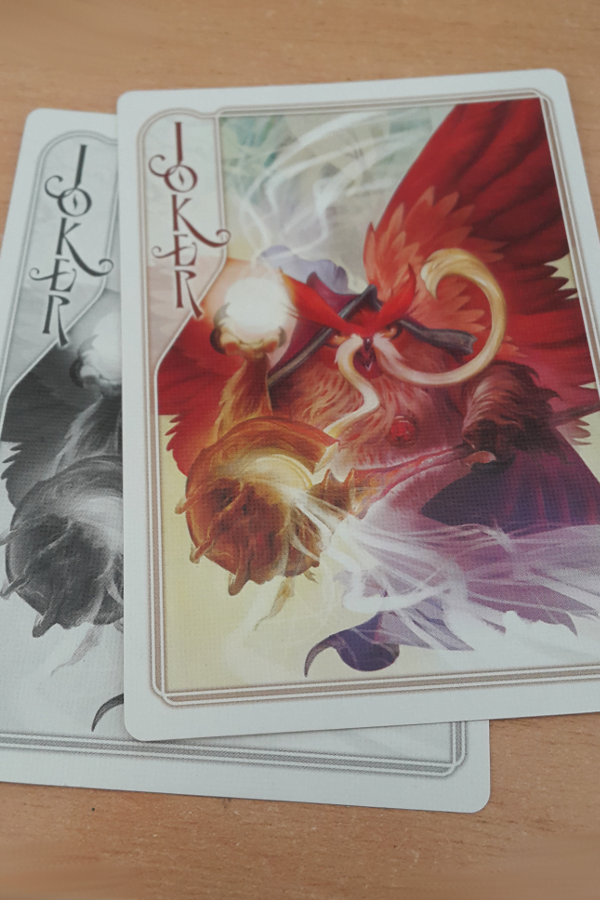

The game comes with a pair of joker cards. These jokers are non-game components, not really, but they do signal something this game treats as very important: Modules. If you check through the rules, there’s a note about how many parts of this game are technically optional, and these jokers are included to allow for other, additional rulesets.

This is really daring. I honestly don’t think I have the courage to release a game with components in it that don’t do anything yet, with the idea that I will eventually fix that, and that it’ll be worth people’s time. Of course, this game owes a lot to Poker, so it’s not like there’s a shortage of possible rules variant sets to work from.

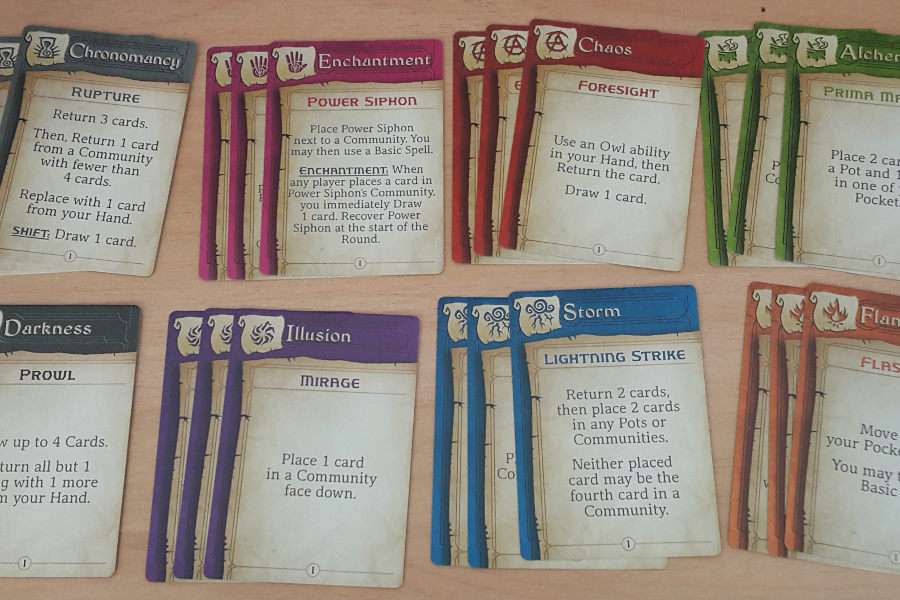

Next up, we havethe spell cards. These are individualised to a player; if you’re the Storm mage, you have all the storm cards. I like this as a flavour idea, and I like it as well as a set of only 3 cards, meaning choices aren’t necessarily very confusing. I do have something of a problem with them in that these cards being cards gives you possible uses for them – like how Enchantment cards can be removed from your spell reserve and placed in places in the game to confuse/set rules and be reminders – but that’s not used in things like the Storm spells or whatnot.

This means they take up a lot of space, which again, is bold: This game is willing to use a lot of space for reminders to make the game handleable.

What’s the purpose of these cards? Why have them? Well, they can make the game more exciting with more players. They give players directly different play experiences that they only look at themselves – it doesn’t matter what you can do from turn to turn, what matters to me is what I can do.

Again, as with the jokers, these components aren’t necessary to play: If they’re too confusing or you’re introducing players to Hocus, these aren’t essential. They also are a major way to lend flavour to the game. Few games are good at conveying the way we often talk about mages in fantasy narratives – a storm mage, an enchantment mage, a time mage – because they often systemise spells a lot. Hocus leans into this.

Also, the typing means the themes of each spell set explain the mechanics, intuitively. The mechanics of how an Alchemy Mage’s cards work are informed by the fact they are Alchemy Mage cards.

Score tracker cards, lovely elegant mechanic. They, as with everything else, look really nice. I’ve made this kind of design and I honestly think this is one of the better examples. Here, they’re depicted showing 2 points and 28 points.

I think the thing about this design that beats my Middleware design is the game is made so its scope only goes from 0 to 39 and that means you only need to turn the card over once or twice – you don’t need to scope all the way up to 80 by rotating cards. It’s tidier.

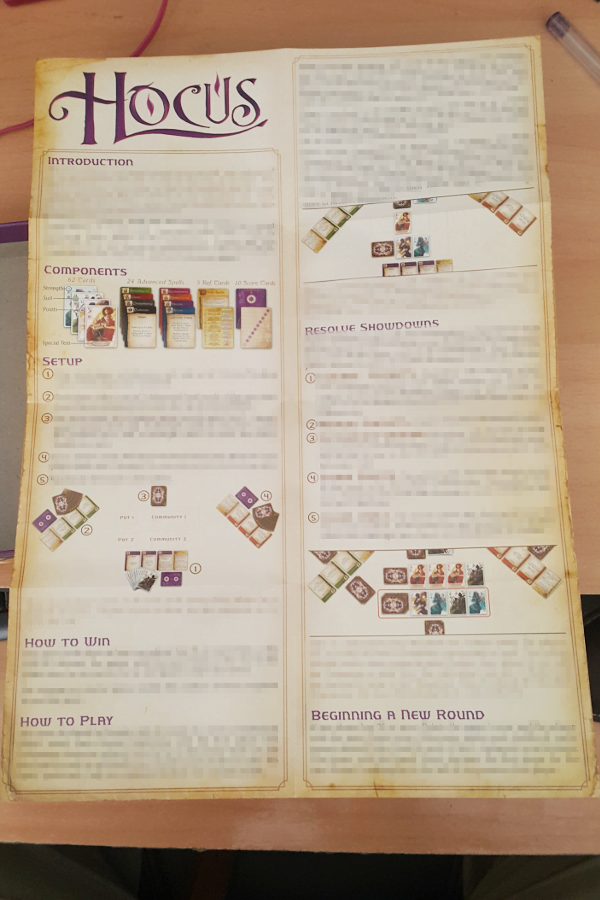

The rules here have been blurred out not because they’re sensitive but just because I don’t want to make that focal. This rules page is a single page, and shows that good use of margins. Clear font, readable, and shows a step-by-step play sequence, with illustrations. This is a really nicely done one!

Another thing to notice is to look at how the How To Win section of the rules comes before the How To Play. This prioritises the way players think of the things they’re learning, lets them know what they want in the game rather than just the sequence of how play unfolds.

Finally we get to these, the simplest cards. There are four suits of cards – now here’s a weird thing. Despite my efforts, I can’t find the names of these three suits. I mean, I go by Cups, Swords and Pointy Hats, but the green naturey tone of the Pointy Hats make me wonder if it shouldn’t be something like Druids or Staves or something.

Except the symbol of the stave shows up on the next type of card:

Owls! Owls are like if one of the sets of cards happens to have a bunch of special powers on them, ranging from card to card. Again, this is an optional rule-set, but it is published on the cards as is. You could make a simpler version of Hocus without these, but if you wanted to ramp that version up and make it more complicated, you’d be left needing to print new material or a reference sheet of some sort.

A dissection of the most complex card type, an Owl. The four components are really easy to signal. From top to bottom, the components of the card are:

- Value: The value of the card. Easy to make a set of these, numbering them zero through fourteen.

- Suit: Again, this is easy to make a variety of. Suits are so uniform a game concept it’s not hard to explain this.

- Reward: The value this card gives you if it’s in a Pot and you win it. These are tracked on the tracker so the cards don’t become removed from the game for a lasting period. If you do things that way, that’s another mechanic to bear in mind. Maybe good mechanics you want to reuse may have a spicy pot total so you might want to choose between getting rid of the card or not.

- Rules: The details that separate Owl cards from others. Rules let the Owl cards do something distinct or different when played. This is a good example of how little space needs to be dedicated to good, well-explained rules.

Hocus’ components signal to me a game that’s done a lot of thorough, very specific examination of a game that was refined over and over. Which stands to reason – it’s a poker variant, and it’s flat-out honest about that.

The main things I see myself wanting to take away from Hocus are good ideas regarding the rules structure (pots, communities and pockets), but also its very strong, very clear idea of one of those procedural games I talked about, a game that’s composed of mathematically explicable pieces. Then, the designers layered atop the clear procedural components spicy, variant rules structures.

Game Pile: Full Throttle: Remastered

Get your keys and keep up.

Remakes: Reboots, Remasters and Recreations

In the age of the easy remix, the re-use, the recycling of media concepts and design spaces and cultural concepts. It’s a space where we have a lot of different terms being used for different kinds of media. For my own purposes, I feel I need to define the meaningful differences between Remakes, Reboots, Remasters and, with new and fresh examples, Recreations.

The Remake is a global term, here. It’s just used so vaguely that it’s hard to really pin down what a ‘remake’ is. Was Full Metal Alchemist: Brotherhood a remake of Full Metal Alchemist? Sort of. Basically, in this case, I’m going to use remake as a way to refer to any new work that’s a new form of an existing work that’s designed to not require previous experience with the work. Each of these other terms refers to a specific type of remake.

A Reboot serves as a way to restart the work, a new point for someone who had no experience to start experiencing the work. A reboot wants to build something out of similar space, wants to use the iconography, it definitely wants to evoke the original, but a reboot is notable for showing you what the rebooter thinks matters to the original.

Here’s an example of four different reboots in one series: Each one was meant to accommodate major changes in the environment the franchise wanted to exist in.

Reboots are really at their best when there’s not a lot of there there, or when you’re making a work move from one form to another. While you might not consider an adaptation a reboot, they both use the same tools. It’s about taking away as much of what doesn’t work in your new form.

A Remaster is more like a translation: Conceptually, you are trying to make the thing again, that functionally works the same way, but with the new tools for presentation. It’s better audio quality, it’s more sound channels, it’s higher resolution images. In the case of some material forms, like film, a remaster can be just taking the production-quality materials and using them to create a new consumer-level version.

The recent trend towards remastering Lucasarts properties – or perhaps just a few classic examples like the Monkey Island games has had different variations on this. In the case of Full Throttle, pictured, the overall spirit is very much preserved, probably because they could work from a lot of similar sources.

One possibly controversial example of this usage of a Remaster is Gus Van Sant’s Psycho, a shot-for-shot recreation of the original Alfred Hitchcock movie from 1960. While this Remaster didn’t involve any of the original footage in creation, it nonetheless sought to be a version of the original in as high a quality as possible, with almost no deviation from the original.

And finally, the most challenging to do well: The Recreation. A recreation, for the sake of this conversation is something above and beyond what a Remaster or a Reboot can do. Recreations are reboots, but, they aren’t just about starting the continuity of the series over; recreations can be about the new continuity and about replicating the story beats or narrative components of the original.

The thing I need this term for, however, is Voltron: Legendary Defender.

Voltron: Legendary Defender isn’t just an attempt to tell the story of the original Voltron series, any of them. It’s not an attempt to update the same plot beats and introduce us to that story. Galaxy Defenders is a recreation of a feeling of the way the original series worked out. It’s a series that takes the same basic idea and ideology of the original story and tries to tell a new story with the same pieces.

The issue I have is that if you simply call it a remake that can miss the basic premise of what the series does. Voltron: Legendary Defender is a series that wants to be the Voltron series you remember and know isn’t there if you ever went back to look for it. It’s tight, dense, and it uses a the set of storytelling tools, animation tools, and trope frameworks we’ve developed in the twenty-five years since Voltron was new. There is, simply put, a lot of stuff in Voltron: Legendary Defender that wasn’t at all in the original Voltron.

Maybe this is all a bit unnecessary. Maybe I just want to tell you how cool Voltron is. Maybe I should just dedicate some time to that. Well, listen, you.

The Scope of Paragon City

It’s been five years, more or less, since the end of City of Heroes. The game found itself a major, important part of my experience, of my learning as a person, as my interactions with culture and with a rare kind of big, creative space.

As the time goes, as it filters on by, things come back, memories, reminders… and sometimes, the things you remember are… strange.

Like…

City of Heroes was big.

It was a little talking point amongst us – which was meaningless – that the biggest zones in our version of the game was Independence Port, which was so vast that you could fit the continent of Azeroth or Durotar inside it.

That’s nonsense, of course – the comparison just isn’t meaningful, and being ‘bigger’ isn’t any kind of better. But it put me in mind, as I remembered this point, of the long, slow walk down Faultline streets before I had a travel power, fighting my way through random spawns to make my way to the door at the far side of the dam.

It made me remember Dark Astoria, my Dark Astoria, the Dark Astoria that mattered to me, where the quiet, hollow streets, full of fog and silence and zombies werer my crisscrossing pathways where I methodically entertained myself by smashing into pack after pack after pack, destroying, moving, again, again, again, filling my pockets, running onwards.

It made me think of the spaces between islands, when you were hunting badges with a half-remembered idea of whereabouts you were supposed to going.

It made me think about flying, about the way you could move so fast in that game, and yet, despite the speed of it, you could travel so far and so fast… and there was still space for you. The distance, the sheer size of that game.

I still miss it.

I miss being able to take my friends and show them this great, big space and say look at this cool space, where you can create your own thing.

Ah well.

All images here were obtained from Google Image Searches and several went to defunct photobuckets. Sorry! :(

Leverage – Sophie

We’re first introduced to Sophie, as a character, as a fifth-ranger character, someone who’s introduced because the other characters are known factors. That’s when we’re given her generally defining characteristic: Sophie is someone who wants to be a legitimate actor, but who is terrible at it. Her skill as an actor is only brought out in cons, where she can somehow slip into character – a range of characters, even – excellently. This is a trait that’s only really emphasised in the first season – the recurrent theme of her being dreadful as an actress, despite regular and repeated efforts to be one. It’s usually used as a joke or a continuity nod.

One of my favourite examples is when Sophie is soliciting feedback from the crew, you get to see how they all handle being confronted with a friend they want to lie to: Nate attempts to bluff his way over the line, Hardison and Elliot are both extremely uncomfortable, and Parker, being Parkery, indicates she loved it, in no small part because she had no boundaries for what constituted normal.

That’s our basic tension of Sophie: She’s really, really good at something, and she’s not good at it in the way she wants to be. As the story progresses, it gets worse for her: Her skill at keeping people at a distance has holes in it to start with, and she gets worse and worse at it, with events that shake her feeling of safety and inviolability. By the time someone attempts on her life, she literally runs away from the group in an effort to re-establish some sense of control over her life.

A sense that doesn’t return until she’s back with them, and that was perfectly timed to the actress’ pregnancy, but anyway.

Sophie is typically presented as a mother character in the found-family structure; she’s the one who sides with Nate in public to allow for some comforting structure, then restructures the complaint to him so he has to address it. The suite of tools she brings to the table are also some of those that have – in a broad, general sense – appeal to people like, well, my mum.

Sophie doesn’t punch people, doesn’t force people, she doesn’t even acquire secrets or slide around back doors. Sophie walks up to the front door and uses confidence in its purest form to manipulate the people she’s dealing with. When the time comes to convince people of things, she does it by showing them things that fit the world that they expect to see, and relies on them to make a natural mistake. It’s very compelling, it’s artful; she constructs a fantastic vision of the world and makes people around her feel it is true for long enough.

At the same time, the character of Sophie is one who more than any of the other characters, connects to real things. She’s not nursing some deep trauma, she isn’t dealing with reconciling visions of herself or enormous guilt. She isn’t addicted to power or success, Sophie is a person who most primarily is interested in what money lets her do, and once it becomes possible, who that lets her help. Even in the earliest part of the series, she leaps to using the tools she has to make people’s lives better, taking over from Nate when he’s too black-out-drunk to get involved.

Sophie is, in this way, an everyperson character to connect with. And as an actress, in a piece of media that requires actors and actresses to make, it serves as a meta reminder that she is letting us step into that work and fantasise for a time about being very good at making people believe us and using that power for good. Maybe that’s all Leverage needs to do. It’s a series that teaches us about things – real things – that are bad, and cruel, in our world, and frames them as things that we should want to oppose, things that we should want to deal with.

It’s a small thing, but it means that when things like Wage Theft come up in the news, our response isn’t just ‘oh well,’ but are instead deeply angered because we recognise what those problems are.

And Sophie, for all her sophistication and her fantastic personality, her ridiculous realities that she creates, she is the person we can see like ourselves, helping to push against them.

Or maybe not. Maybe you’re like me. Maybe Sophie doesn’t ring for you like that. But I’m absolutely certain, that for everyone who wants, in a story like this, for there to be someone as The Adult In The Room, feel gratified and relieved every time they hear Sophie step up and assert exactly that.

Booth’s Unstructure

Here’s a term that game developers should know about from academic spaces:

Unstructure

Unstructure is an idea from Paul Booth’s Game Play: Paratextuality in Contemporary Board Games. In this book Booth needs some way to describe the concept space that games create that is both concordant with human-manageable rules, and yet not immediately procedurally compatible with human interpreters.

Big mouthful there, so let’s try rephrasing it. Unstructure is the way a game uses systems that a person can manage to create scenarios that people can’t immediately predict. Some games don’t really have unstructure – Blackjack, for example, or Bridge, or Backgammon, for example. Games that do, however, are those games that are usually trying to represent a world with many people acting in it, some of whom aren’t really ‘in’ the game at all – the movement of traders, or the behaviour of monsters, or the whims of traders and people. Even a game like Monopoly has unstructure, where it uses chance and community chest cards to represent the goings-on in the players’ lives that have nothing to do with their surveying and buying property.

Unstructure is a thing for games that are trying to create a metaphor or a hypothetical space. The example of Unstructure that Booth uses in the book is Arkham Horror, a game that spreads systems broadly across a board, across different subsystems – people you deal with, events that happen, monsters that act – and in so doing creates a scenario that is both generated by things you can look at, read, and explain to toher players, and understand, that is still complicated enough that you can’t necessarily solve it.

A game Booth doesn’t cite in the book but which serves this really well is Betrayal at the House on the Hill, where the systems of the game are extremely well suited to hide from you just what haunt will happen, how it will happen, and who is going to be the traitor. This works really well in that game because it keeps you from being able to predict who will be the traitor, putting a spicy edge on the cooperative exploration part of the game.

The reason I think you want to know about – and have access to – unstructure is a concept is because it lets you know what you need, how much of it you need, and ways to build with it or build away from it. What Unstructure gives you is a way to describe just how much stuff you need going on in your game that players have no control over, and whether or not those players can manage to keep straight what’s going on. Some games may make it too easy to deduce the behaviour of the game, meaning the unstructure collapses and becomes something predictable or procedural. Some games may make it too hard to perceive random events as being about this world space, and make the game feel fundamentally random (hi, Monopoly).

The reason I think you want to know about – and have access to – unstructure is a concept is because it lets you know what you need, how much of it you need, and ways to build with it or build away from it. What Unstructure gives you is a way to describe just how much stuff you need going on in your game that players have no control over, and whether or not those players can manage to keep straight what’s going on. Some games may make it too easy to deduce the behaviour of the game, meaning the unstructure collapses and becomes something predictable or procedural. Some games may make it too hard to perceive random events as being about this world space, and make the game feel fundamentally random (hi, Monopoly).

Unstructure’s just another tool to describe ways you want the game to work, and it’s worth having.

MTG: Deadend White

Sometimes you have to make sure that you’re willing to bail on an idea when it’s not working. Today, let’s do a quick rundown of something that, in that vein definitely did not work.

First, the list:

[d title=”Deadend White” style=”embedded”]Grunts

4 Lone Rider

4 Avacynian Missionaries

4 Glory-Bound Initiate

4 Thraben Inspector

4 Hanweir Militia Captain

Gear

4 Always Watching

4 Neglected Heirloom

Removal

4 Desert’s Hold

4 Faith Unbroken

Lands

2 Sea Gate Wreckage

1 Geier Reach Sanitarium

4 Shefet Dunes

4 Desert of the True

13 Plains[/d]

First I saw the rudimentary utility of [mtg_card]Neglected Heirloom[/mtg_card]. Seems simply enough, stick it in a deck with a bunch of other transforming cards, and you’ll have something decent or at least get an idea of if the card is garbage. Easy, right? Make the shell, see what you got.

The problem we have here is [mtg_card]Lone Rider[/mtg_card], or more properly, [mtg_card]It That Rides As One[/mtg_card]. Because flipping this creature gives me the kind of critter I really like to have and it’s so big, and it’s so hard to race. And they printed [mtg_card]Desert’s Hold[/mtg_card] in Hour of Devastation, which fits so nicely alongside it! Turn one desert, turn two Rider, turn three Desert, gain 3 life? That’s sweet. You only need to give the rider +2/+2 in any form to have flip-worthy power, and –

Quickly, this deck became about flipping the Rider. And that became about ways to squeak 2 power for 3 mana smoothly. And then it became about finding ways to draw the Heirlooms to feed the Rider, and –

You can see how this became a mess.

Don’t get me wrong. This pile won a bunch of games, but you can win a lot of games in the Just for Fun room by making a deck with 24 land and a bunch of creatures with a curve. There are things that will just stumble and fall, and you’ll take them out at the kneecaps. That’s just how it goes. But, this deck was still this deck, and it still faced the problem that it failed against opponents who were prepared, and it really failed against opponents who could adapt. People who could correctly time removal, or hold mana up for Rider flips, for example. People who didn’t run a lot of creatures, leaving deserts dead in hand. People who had some way to attack other than attacking my rather plump life total.

On almost every angle of attack, I was not quite up to it compared to what my opponents were capable of doing.

So there’s the deck. The only really cute thing in it that I still like is the interaction between Exert and Always Watching, but guess what? There’s a better deck for that in Red White, and that deck is a real beast to put together now.

Price

MTG Goldfish cites this deck as being about eight bucks. If you plan on playing with Always Watching or Glorybound Initiates, they’re the main things of value in the deck, so it’s not such a waste to play around with.

No Capes!

You ever see something you fundamentally disagree with become the like, unifying meme of a realm of art and media culture that the people who repeat it literally have no opinions about? Like, you get to see as people who don’t care and don’t understand just parrot an opinion that you know is wrong but they also have no idea or framework for explaining or talking about why it’s wrong so if you shouted at them you’d be the asshole?

Yeah, Edna Mode sucks.

Game Pile: Discworld

We’re doing something a little bit different today.

While, yes indeed, we are going to Game Pile about a game, we’re going to talk about 1995’s Discworld, a point and click adventure game originally developed by Teeny Weeny Games for Psygnosis, based on the fantasy novel universe of Sir Terry Pratchett’s Discworld. This isn’t a game you can buy – but it is a game you can just have, if you’re the kind of person who doesn’t mind setting up a copy of Dosbox and maybe throwing a few dollars to Abandonia in thanks for their time and effort archiving videogames.

At this point in games’ history, the CD Rom is new, voice acting is just becoming widespread, and the point-and-click is in something of a golden era, because the interfaces are getting better, resolutions larger, and storage space for background graphics are even more diverse, allowing for absolutely sprawling games with an enormous variety of locations and a chance to show some truly wonderful splendour off.

Basically, this game existed at an intersection; it was an era of hand-drawn background art, voice acting on the rise, and before 3d technology pushed us into the new uncanny valley of box-kite people yammering at people, and the delightful tech-orientation of people like Sir Terry Pratchett and his friend Douglas Adams meant that the idea of making a Discworld point-and-click adventure game could happen at all.Continue Reading →

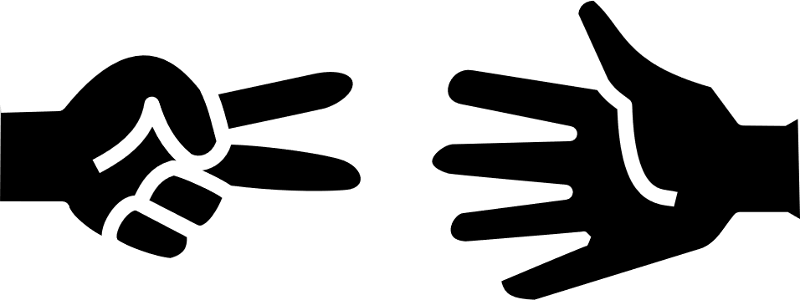

Mechanic: Turn Order Chicken

There’s a mechanic I’ve been thinking of lately, considering a game to put it in, where players determine an action order by showing fingers at the same time. So players count three, two, one-

And then everyone holds out a number of fingers equal to where they want to be in the turn order. So you could go first if you just hold out one finger. You could go second with two, and so on.

Except if two or more people show the same number, bam. They all get bumped back. If turns in this game are super fast, then that’s it: Everyone who picked the same number loses this turn and has to go for the next one. If turns are a little more elaborate, like a worker placement game, then the players who didn’t pick the same number as anyone else pick up, like, turn order tokens, then the players who remain have to go again. So if you pick 2, another player picks 4, and two players both pick 1, the player who picked 2 takes the 1st-place marker, the player who picked 4 takes the 2nd-place marker, and then the remaining two players have to fight over the 3 and 4.

So, players need to not get greedy, they need to pay attention to the turn orders their opponents are going for, and they need to know when they can get greedy. Maybe the game for this is super small, like a tile placement game where it’s just a matter of trying to place them well or cleanly?

Notes: How Disney Uses Language

- Comparisons between Frozen and Moana are sort of a sign that right now, because they’re only one of a small number of films with the similar premise (woman-centered narrative).

- The riff in both Jungle Book and Aladdin feel kinda like the Oriental Riff, aka Aladdin’s Cave that opens a lot of other things like Turning Japanese. Like, the iconic ‘Oriental Sounding’ music isn’t from anywhere in the Orient anywhere.

- Cultural Appropriation is a big topic and it’s hard to talk about it in Youtube spaces, and it’s even harder to talk about on Twitter.

- The Bulgarian choir music thing is just straight up super interesting.

- Is this fusional, using Bulgarian choir style with the Inupiat lyrics?

- The thing about Librettists and Operatic Composers amuse me juxtaposed with a Gilbert and Sullivan quote because they hated each other so much by the end, because they couldn’t see it as a synthesis of their work.

- English is a fixed-stress language; words have a proper emphasis in them, but words don’t have a proper emphasis in a sentence, or rather, the emphasis tends to indicate the subject.

- Vocables! There’s like, a language for singing, in a language? That’s super cool! I wonder if it’s also part of transmission/commonality between cultures, so they can all sing the same songs even if their languages change over time and space.

- I really do want to see Moana. It looks really great.

- God, Lilo and Stitch was also great.

- The question of cultural appropriation between Hawai’i and France and Polynesian narrative.

- I really, really love the detail that the characters are singing the song in its original language, and then they stop singing it when the language shifts to English. It becomes nondiegetic, which is really cool.

- This form of video isn’t actually so demanding of production values. I can do this. I can do this even with Microsoft Movie Editor.

Leverage – Hardison

One of the lines of Leverage is that there are no new tricks under the sun; the idea that there aren’t really extra cons going around, not new tricks being invented, just different methods for the same four or five basic conventions. This is an old art, an art that’s been in practice now for centuries.

It can be very hard to believe this when you come at the world from Alec Hardison’s perspective, the life of someone who grew up online. Where everyone else in the crew is schooled in old-world practical confidence tricks, what Hardison knows is mostly self-taught rediscovery of these plans: About exploiting information that others don’t necessarily have, or even know that you have.

The other thing is this means that Hardison’s type of manipulative confidence trickstery is always of the same, simple, consistant method of character. When the time comes that he’s on the spot, and needs to come up with a character, or an idea, or some way to keep people from asking too many questions, he has one, extremely rudimentary genre of character traits. Hardison defaults to being a facile, insincere, extremely rude and volatile, and often socially gross character in an attempt to convince people that whatever is going on, they absolutely want him to go away quickly.

Simply put: Alec Hardison is a troll.

It’s not really a nice element of his character. It means that of the two most awkward, homophobic and transphobic moments in a show that almost always strays from actually being hateful or racist, are laid square at the feet of Hardison. This is especially rough when you remember that otherwise, he’s one of the nicest, most human characters in the series. He’s fun! He’s funny!

Shame he’s gotta be the one who goes and does the two Not A Good Look moments.

I guess it wouldn’t be a complete discussion of Leverage without my personal take on this particular problem and a framing that if not excuses it, at least renders it somewhat forgiveable.

Hardison is a character who speaks about his history, his childhood. The foster home that raised him featured a heavily religious mother figure, and her values were the values imprinted on him as the world at large. It’s clear that Hardison never became centrally religious, never really took on values like ‘thou shalt not steal,’ but he still was very shaped by her in the forms of lessons about what he figured most other people considered to be a normal, proper way to live.

Basically, Hardison goes to a gay stereotype for one con, pretends to be a trans man for another, because he’s a troll, and he’s trying to make other people uncomfortable, and he knows those topics do it.

I’m not saying it’s forgiveable; it’d be nice if those moments weren’t in the show. It’d be nicer still if those moments didn’t come from characters who were themselves presented as normally, conventionally, the heroes. At the same time though, Hardison’s tricks are not presented as things he really believes, but rather things he believes would make other people uncomfortable.

Hardison is a character who loves someone neuroatypical; a character who wields indignation about marginalisation and abuse as a weapon in social situations; a character who values learning and information and loves technology and devices, and, when put down to it, wants to make things right and make things okay with his friends.

Hardison is a character with a lot to love. There’s wits, there’s cunning, there’s also a playfulness, a love of nerd culture, an appreciation of indulgence. When asked about his abilities, he is cocky, almost arrogant, but he never writes cheques he can’t cash. And crucially, when the time comes for the group, at large, to express its anger, its sadness, Hardison is the one who expresses that.

When the family is invaded, when they are directly under attack, the moment that sings in the memory, isn’t Elliot’s physical rage, it isn’t Nate’s low-key threats of massive destruction. It’s Hardison, the one who shouts Get Out Of My House.

Zootopia!

In 2015 I did not see any movie at all in a theatre. In 2016, I saw three; one of them was Deadpool, which I saw on a record heat day with a free ticket, and the other two were both Zootopia. I not only liked Zootopia, I liked it enough to see it twice. So here’s your spoiler-free penny-ante review and then I’m going to jump below a fold to say something about the specifics in the universe, about the storytelling of Zootopia:

Zootopia Is Really Good. I liked it a lot and I hope you enjoy it if you haven’t seen it.

Well, now, the writing about Zootopia is already widely written. I mean, I’m in that particular overlap of the world where I can watch a community of people I respect talk about how this show is basically hate crime, because it makes cops look like human beings. And how it fatshames. And how it’s fascist to want traffic cops.

Continue Reading →MTG: Anointment Everlasting

It’s funny to me just how quickly I get bored of decks in standard. It’s probably a byproduct of standard being very big, but also the standard environment being full of small things that don’t work together too exceptionally well. I can’t play with all the things I want to play with in a 60 card deck, which means instead I make a bunch of different, interesting things.

When I sit down to play I tend to bias heavily towards extremely aggressive, or extremely passive. I don’t tend towards combo, and when I do, it tends to be a really well insulated, extremely safe combo that can be sort of hidden away in a shell of a different deck. I just don’t like trying to Assemble The Machine under pressure.

This obviously means I tend towards red and black as aggressors, since they have reach, and I love my green beef so I almost always play with that in some way, and all this means that when I do play an aggressor, it is inevitably playing anything but Blue And White. They’re not my thing, they don’t tend to have the kind of reach or aggression I really like.

Anyway, here’s a blue white aggressive deck I’ve been playing and enjoying lately.

[d title=”Anonited Eternals” style=”embedded”]The Bodies

4 Trueheart Duelist

3 Adorned Pouncer

4 Wharf Infiltrator

2 Vizier of the Anointed

4 Sunscourge Champion

4 Cloudblazer

4 Vizier of Deferment

2 Vizier of Many Faces

2 Aven Wind Guide

The Juice

4 Anointed Procession

3 Farm // Market

The Lands

9 Plains

11 Island

4 Irrigated Farmland[/d]

The last time I played Blue-White aggression for any length of time, I was playing a Return To Ravnica era Arrest-based Enters-The-Battlefield deck, spread out into modern to include the combo of [mtg_card]Ghostway[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]Archaeomancer[/mtg_card], and, of all things, [mtg_card]Sky Hussar[/mtg_card]. Which I love. Don’t @ me.

This mainly taught me that for my tastes, a UW aggressor deck needs some way to really sustain itself. It needs something it can do to juice up later. In the previous deck, it was the ability to perma-vigilance your team and endlessly recycle arrest affects to keep opponents from necessarily slamming you down with superior creatures. Much like [mtg_card]Lightning Bolt[/mtg_card]s and [mtg_card]Zulaport Cutthroat[/mtg_card]s give you some way to break up a stall or go over the top, this deck needed some way to take over the board, some way to make early plays into really juicy late plays.

And thus we meet our buddy, [mtg_card]Anointed Procession[/mtg_card].

Double Trouble

I played with [mtg_card]Doubling Season[/mtg_card] once; I played with [mtg_card]Dual Nature[/mtg_card] in Commander and in Extended (it was a thing!). I played with most of these effects, and so far, I think this is the best use of this effect I’ve ever played. With those other cards, with the decks those cards had to fit into, Procession doesn’t care if you get the token-makers before it or after. Embalm and Eternalise feed into Procession elegantly, both before and after it on the mana curve. It’s not like the awkward math where you’re left wondering ‘wouldn’t the [mtg_card]Mycoloth[/mtg_card] have just won this on its own?’

Procession lets this deck treat its graveyard like a second much scarier hand. I’ve had games end on the spot after I drop a procession and untap to Eternalize [mtg_card]Adorned Pouncer[/mtg_card] times two onto the battlefield. It even lets you do silly things like copying two things at once with embalmed Viziers.

The deck’s threats, overall, are hard to counter – and I mean that as killing or counterspelling, and even creatures traded for a card typically to go to the bin and wind up embalmed or eternalised for more head count. There’s even a durdly toolbox effect where the [mtg_card]Vizier of The Anointed[/mtg_card] can go hunting up other things – and if your opponent has a great big creature, you can steal it with your [mtg_card]Vizier of Many Faces[/mtg_card], then trade them, then bring back your vizier as two also-huge creatures.

The sad thing is, I sometimes feel like [mtg_card]Cloudblazer[/mtg_card] – the reason I started making this deck! – might just not be a good fit for it, since at five mana is when you’re bringing bombs out of your graveyard! At the same time, though, it’s an incredibly juicy target to Vizier of Many Faces with a procession – four or five cards, and four life!

Still there is at least one critter that needs some explanation and that’s the [mtg_card]Wharf Infiltrator[/mtg_card]. Synergy between the Infiltrator and Eternalize and Embalm is a tiny bit obvious; you can have a turn three of attack, ditch a [mtg_card]Trueheart Duelist[/mtg_card] or [mtg_card]Sunscourge Champion[/mtg_card], and then you’re left with the possibility of making a 3/2 Eldrazi (for no real card loss), or embalm the duelist, or, say, make an Eldrazi, play a tapped land, and untap into something like Sunscourge Champion Eternalized.

Notably, the Infiltrator can make a 3/2 off any discard, not just their own, and if you have two of them, you can serve, discard one card and make two 3/2s or if you’re feeling saucy and it’s late in the game, discard two cards for four 3/2s. And that’s without their interaction with Procession.

Price

With a quick check at MTGGoldfish – and I use them because they have a tool that makes it easy and free to check, not out of any particular love for them – this whole deck costs eight dollars to make. The bulk of that price is five dollars for the Irrigated Farmlands – which, again, I will stump for: Buy dual lands if you cans.

Followup Update

Real quick, here’s the most recent build of the deck I’ve been playing when this article comes out. I like this deck a lot and keep playing it when I mean to go do other things, play other decks for other articles.

[d title=”Anonited Eternals 2.0″ style=”embedded”]Creatures

4 Thraben Inspector

4 Sunscourge Champion

3 Vizier of Many Faces

3 Trueheart Duelist

3 Adorned Pouncer

4 Wharf Infiltrator

Vizier Toolbox

4 Vizier of the Anointed

1 Sacred Cat

1 Anointer Priest

1 Glyph Keeper

1 Aven Wind Guide

Spells

3 Anointed Procession

4 Farm/Market

Lands

4 Irrigated Farmland

7 Island

13 Plains[/d]

Two quick notes: The Sacred Cat is there when you have other Vizier of the Anointed out so you can play a second Vizier, pay a single mana and draw 2 cards. Also, Oketra’s Monument doesn’t seem to work super well with this deck in testing, because A. There’s a better Monument deck, and B. this deck doesn’t cast spells as often as it Embalms or Eternalises.

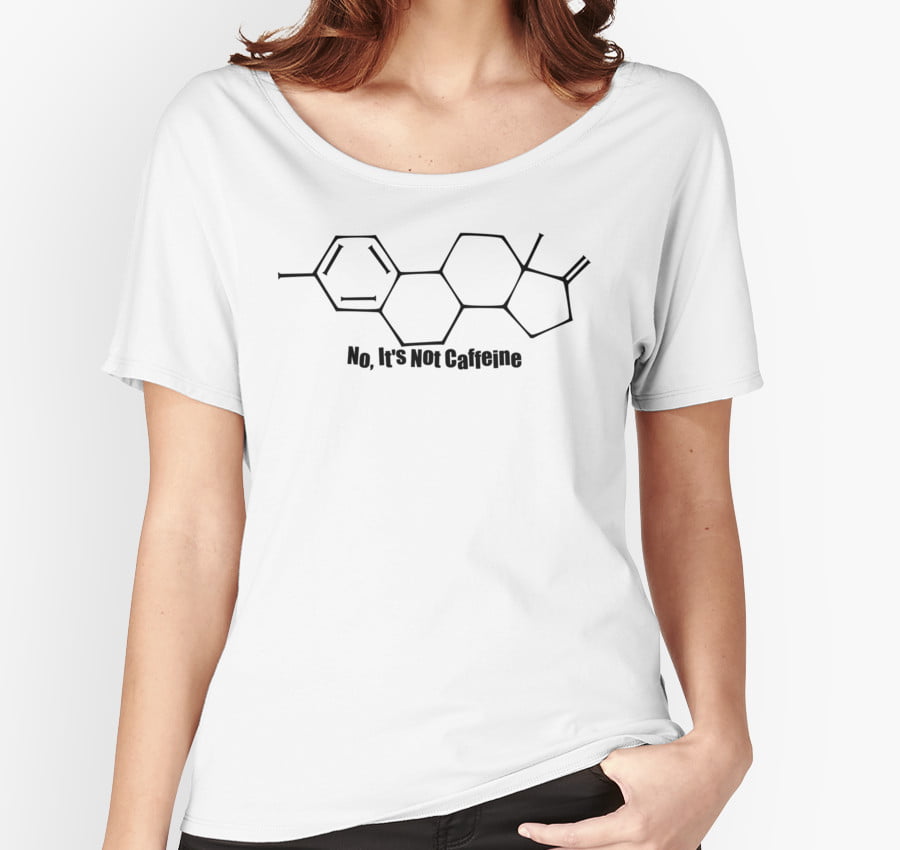

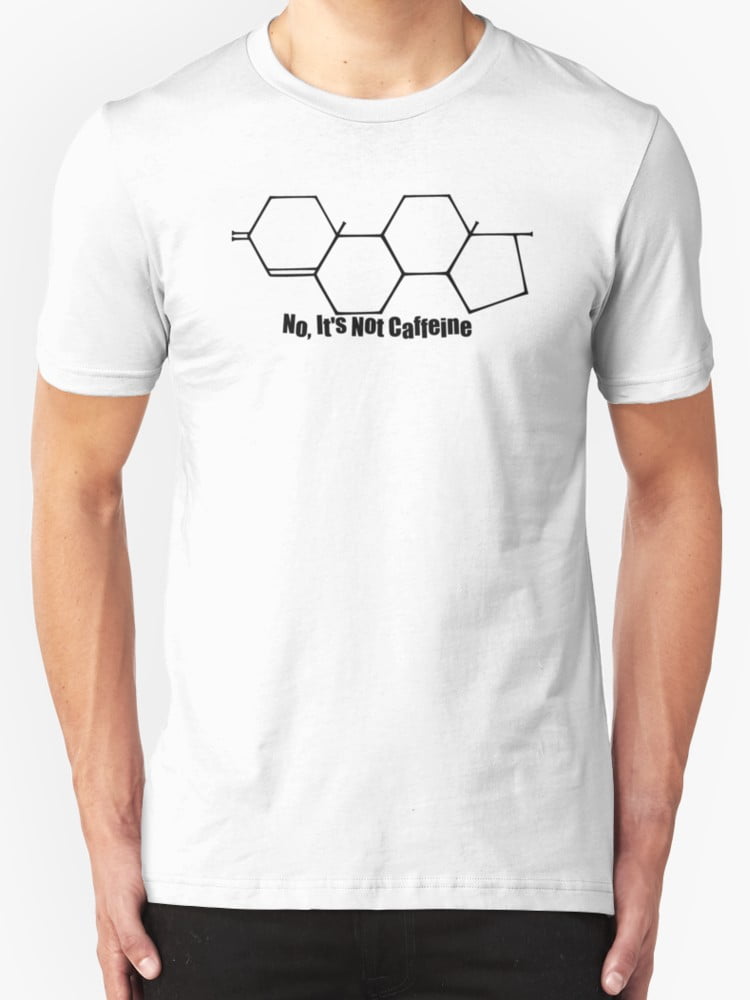

Shirt Highlight: No It’s Not Caffeine

Hi there! Did you know I did shirt designs on Redbubble? I wanted to show some of them off, because these are designs I’m proud of!

This time, I wanted to show off these two t-shirts titled No It’s Not Caffeine, made for my trans friends to wear on their bodies. To explain, these two designs show the chemical symbols for Estradiol and Testosterone respectively.

We in the geek community like showing off chemicals that mean something to us, and with that in mind, I thought it’d be interesting to put some more advanced chemistry lessons out there. I mean, it’s not like I’d have any means to read it myself, because I didn’t do chemistry at school –

like at all.

These shirts are available for you to purchase if you like the art I generate and want to put it on your body! It’s also available as a sticker or a notebook cover, too!

Game Pile: The Samaritan Paradox

Let it never be said I fail to strike when the iron is gone. Remember how a few years ago there was that fuss about the kickstarter for Broken Age, a point-and-click adventure game that would Bring Back the point-and-clickers of the 90s, which were…

Yeah okay.

The thing is that time period of games isn’t some preserved bubble of media that lives back then and never extended. The point-and-click adventure game never went away, it just stopped being so high profile people were paying $120 for big box releases. The point-and-click genre kept moving, the tools became more available, and with it, we saw more and different approaches to storytelling. It stopped being the spoofy work of the Space Quest franchise, the storybook fantasy of Kings Quest, the high-cinematic weirdness of the Lucasarts franchises.

As it grew and it spread, we got to see stuff like this, The Samaritan Paradox, which I can only describe as an example of, say, European Cinema as an aesthetic in a point-and-click adventure game. So let’s all don our berets and smoke our clovey cigarettes as we delve into the thoughtful, cryptic differently structured work of The Samaritan Paradox.

Do Daddies Dream Problematic Dreams?

I’ve written about Problematic in the past, with the simple premise that there are no non-problematic faves, and the baked-in nature of the colonialist world we live in is fundamentally damaged. Recent events (a hot take shot from the hip) put the term in stark relief and so, since you’re all so very interested in telling me what I should think about it, clearly you’ll be interested to hear me expound. Right? Right? You’re not just looking to complain at a stranger?

This is spurred in part by recent reading about Dream Daddy. Because that’s a thing I started caring about despite having literally no interest, whatsoever, in wanting to play it, for any reason, at all, gosh dangit. With that in mind there’s going to be a minor spoiler to a thing I don’t care about but let’s take it under the fold anyway. It also involves the genders.

Continue Reading →

What Do I Think Of Visual Novels?

I’m a big fan of the Visual Novel. I don’t just mean that I have a fondness for the form borne out of a period of my life where they were a way to both get anime and smut at the same time when those were two things I very much needed in my life to feel connected to the world around me, I’m actually a fan of the structure.

There’s a lot to talk about here so let’s just dive in.

Accessible Moviemaking

I know a lot of people who want to make movies. For some of them, the cinematography of a videogame camera gave them that option, and you saw early demo-editing Quake levels and replays being made to play with those same ideas of echoing subtitled cinema.

I see the Visual Novel as a less kinetic, but more framing-based example of this same basic idea. Good cinematography, an appreciation of good cinematography, makes visual novels a good avenue to construct scenes as if one is thinking in terms of movies, in terms of what keeps people compelled.

So first of all, they’re a way you can do a movie-sized story on a very, very small budget.

The Point-And-Clicker

When it comes to the game elements of the Visual novel, I feel that as a game type, it inherits well the basic structures of the point-and-click adventure, those low-impact, low-action kind of games that wanted to give you the time to quietly and patiently sort your way through problems that are presented to you. Things like Monkey Island and Beneath A Steel Sky, where the point was not some focus on exciting action setpieces but rather a much more slow, wandering kind of puzzle hunting.

Now, there are four basic puzzles in point-and-clickers you can deal with, and there are two that Visual novels can do just fine, and two they do Not So Fine.

Good: Use Key On Door

Something impedes you from a path ahead. For good conveyance, you want that path to be in some way visible to the player. You need an object that you can carry to the impediment, and then that will get it to go away. Ie, it’s a key and door situation. There’s a door, you unlock it, you can continue on your way. This type of design is incredibly common. Sometimes you’re obscuring the keys, sometimes you’re obscuring the doors, sometimes behind the door there’s just another key, sometimes you’re just collecting completely obtuse keys – but that’s the basic thing. Take an object to an impediment.

Bad: Put Apple In Box

So there’s this thing that’s really tricky to do in Twine, and Visual novels as well, where you have containers. Containers are something some games can handle just fine – I’m told Inform can easily handle it when you put an apple in a box, then pick up and move the box around and then set it down wherever you like – the apple will still be in the box. In visual novel coding… this is trickier.

What this tends to mean is that visual novel games often feature a bit less of characters interacting with the world as a place with a lot of material objects. This is also reflected in the genre – note that most games are not about carrying around tools, as much as they are about inner experiences.

Good: The Language Maze

This one’s a little more common for older games, back before we were voice acting everything. A language maze is – very simply – a series of conversation choices where you need to choose a particular sequence in order to find a point in the conversation that an opponent does something that the conversation would not normally do. Some mazes are really simple – you just ask a character a thing, and you’re given an object. Sometimes, you ask a character a thing, and that gives you some knowledge you’re now able to use later. Sometimes you ask a character a thing, and that gives your character some knowledge you’re now able to use later – like teaching your character to pick locks or something.

Bad: Freedom Of Movement

And now here’s where the point-and-clickers of the past are a little different. The typical form of the Visual Novel is a linear flow of time from A to B. You’re very much moving along a line of time, rather than necessarily having the means to travel between locations. This isn’t to say that’s how things have to be, but it’s not uncommon for people writing visual novels to present them as a single long line of time with you moving along it.

This isn’t to say that visual novels are bad at this – you can definitely set them up to do it. But the default code structure of something like RenPy reflect the genre, where it is very, very easy for the game to just see each play as a series of sequences that check variables, rather than necessarily going to places and letting you move around them more freely.

Scaling Up

Then there’s the things Visual novels can do well that you can lean into and build on in your own projects.

Codeces

Hey, you know how you have all that writing about your game world, or your characters and you want to give people a place to go look for it and read it if they want to? But if you dumped that in the main space for people to read it’d slow everything down and be super boring?

Well, the Visual Novel is a game form where reading a ton of stuff is a thing. In Hate Plus, there’s a reference codex for any character. You find yourself confused by a name? Click on it and it’ll take you to a place where you can look at that character and look at what they’ve done and what you know about them so far.

The Inner Life

It’s almost a stereotype that visual novels have a first-person narrator, often a narrator who is ‘you.’ Doing things this way gives you an almost unprecedented level of access to a character’s inside thoughts, meaning you can see how they think before they act, how their inner dialogue contradicts their behaviour, their anxiety, their stress.

It can also be a fine opportunity to learn that a character is a total butthead, which is a problem that Roommates has.

Day To Day Life

You know that thing about how going to a place is something that VNs don’t tend to do? Weirdly, they do handle schedules well. Because that’s how you use your time, and you can even trigger or chain events based on what you’re doing with your time, today. These can get super complicated, too!

The Wrapup

I really like Visual Novels. If I was better at designing interfaces or had the knowledge of where to start designing interfaces, I’d probably have made some of them by now (Sorry, senp.AI). They let artists do small numbers of works they like, they allow for clean use of arts and assets, and they don’t require a lot of technical knowledge to get started on. They do need you to be somewhat clued in on structure and planning, which is pretty frustrating stuff if you’re not familiar with it – but you can find your plan in the making, too, and restart.

Look into Visual Novels, they’re a great little genre, and lots of fun to think about making.

Leverage – Parker

When you’re introduced to Parker in Leverage it’s with the unfortunate offhanded phrase that she’s ten pounds of crazy in a five pound bag. To be fair she’s also throwing herself off a building.

Parker is a thief, and our introductory shot of her is, in sequence, being shown in an abusive household, having her toys taken away from her, a crying mother, and being told, as a challenge, that she needs to be ‘a better thief.’ Then it ends with her walking out of her foster home, with the toy, blowing up the home.

This is one tiny problem with the earlier parts of Leverage, though really, the first episode. They hadn’t found their stride yet, they hadn’t quite perfectly nailed down the dynamic. The early entries came with a lot more shouting tension between the characters, but the start of Parker’s character was there. She was awkward, she had outbursts at people when they confused her, and crucially, the line, “I don’t like things, I like money.”

Parker liked money, because money made sense. More money was better than less money, and that meant that money was, literally, a way to keep score. She cared about the experiences of theft, but not the value of the things money could do for her. That crucial core of the character, that she doesn’t think the same way the rest of us, was there, and was fleshed out as the series went.

Parker is a character we learn a lot about, mostly because the assumptions about how she is don’t work. You needed to explain why she became, which means there’s rich fodder in showing her stories as connected to greater events, to the inevitable connection to her father figure, to how she learns to care about greater groups of people than just herself, or her family, building relationships within the group.

One of the devices about Parker that I really love, and which reminds me of of all things the Tales of Earthsea books is that because of her neuroatypicality and lack of social context, Parker can be both an eye-level character, who needs things explained to her on a very rudimentary level, and a high-level character who is the one doing the explaining.

Good storytelling in a short amount of time is hard, and Leverage makes it work by doing that storytelling fast. The story doesn’t take breaks to explain to you the large, elaborate history of con artistry that they definitely researched, but instead gives you a short, quick exchange that sounds like characters know what they’re doing (‘Cherry Pie, but with Life Cards’). Parker is responsible for a handful of these – she rattles off details about security systems, about heights and tensile strength and physical athletic limitations of human bodies, and she does so very comfortably.

The other thing Parker does, excellently, is show an emotional vulnerability and obviousness that the other characters resist. Elliot is not going to call the rest of the crew his family: He’s too damaged, too hurt to do that. Hardison can’t bring himself to do it, hepped up on all his personal social values and his ideas of what he can afford to show about himself. And then there’s Sophie and Nate, who are for lack of a better term, the parents of the group, and they don’t show their emotional state so readily.

But Parker: Parker can. Parker doesn’t ‘understand her emotions’ the way the others do, she doesn’t consider that she shouldn’t be so obvious about it.

Parker is a wonderful character, and despite her being neuroatypical, despite the characters early reference to her as being ‘crazy,’ by the story’s development it becomes clear that they trust Parker, and nobody thinks Parker needs to be fixed or solved. Parker’s behaviour is Parkery, and it’s not a sign of the flaw or wrongness in her.

Telling A Story Through A Game Pt. 1

Gunna have to go to the tank for this one. It’s more than one answer.

First of all I have to unpack that me because my model of games and stories is intertwined. To me, games all tell stories, the question is just whether or not those stories are memorable or interesting or cool. Basically, everything can tell a story, the issue is up to the interpreter as to what makes that story interesting or good. I have a model of the universe that has room for crap stories, something that’s apparently resisted.

Another thing that’s strange is that we’re heavily informed by videogames these days which have lately taken to making it so that storytelling is done primarily in the form of unsolicited interruptions. The typical way to handle videogame storytelling is to segregate story elements in safer spaces, away from places that players can mess them up by interacting with them.

This isn’t to say that removing control from a player to tell them a story is a thing per se – I mean, look at games like Undertale (spit), which deliberately tracks a lot of things you do or don’t do and is willing to trust you to represent how and what you do. This sort of storytelling is a little bit like getting a report card at the end of the semester, but that isn’t to say it’s fundamentally bad. It’s a little primitive, but that’s okay.

Let’s say you’re making a storytelling kind of game – those are sort of inherently biased towards it. Some games, like Funemployed, Dear Leader or Once Upon A Time make it the job of the players to tell story in an effort to get from where they are to where they’re going (and hi, check out The Suits while we’re at it). Let’s set those aside, because in those cases, the mechanism of storytelling is what the players are induced to do by the mechanics. The game is presenting you wit hstory beats to move between and telling a story to other players is literally all the players are there to do. Those games create inspiration and sort of dose players with it, hard.

There’s also games that use ‘story’ as their framework, games like Dead of Winter where your storytelling is literally mechanised: Where in amongst the mechanically-generated story, there’s a chunk of systems designed to pull players sideways into a story that’s sort of structured and framed and bolts itself into the story.

This can sound like a criticism, but please, trust me it’s not. It’s just that this kind of system is easier with bigger games, where you can dedicate a component of the systems of the game towards Telling Stories. This system is wonderful, but to keep it from being boring, it needs a game of a particular scope. You can’t make a game that’s just a crossroad deck (well, you can) without players running it out with only a certain number of plays. You want some sort of mystery for people when these story elements jump out at them.

There’s narrative created by interplay of objects. Even abstract games do this – look at how people talk about the story of matches of Chess and Go, the narrative of how a game unfolds. Like I said, it’s not necessarily an interesting story to anyone in particular, but it’s still a story.

That’s our framework: There are lots of ways to tell stories with games, in games and around games, and there are some sort of ‘easy’ places to design. We’re going to talk a little bit more about methods for designing mechanics that tell stories next time and using mechanics to make players think of stories.

This blog post and subject was suggested, as above, by @Fugiman on Twitter. If you’d like to suggest stuff you’d like to see me write about, please, do contact me!

MTG: Improvise Approach

20:22 Talen Lee: I think for all that I like the things this deck does, I never want to play it ever again

It’s a good idea to know what you like when you play a deck. Maybe you like the varied math of making creatures and putting on pressure. Or perhaps you dig the way you change the rules of the game by imposing more force on your enemies. Sometimes you like seeing a mechanism, a device of the deck just working. It’s sometimes about watching a game’s mechanism working without those parts. It could be an elaborate combo of two parts that you wrestle into existence, and then bam they fire off and it’s spectacular or it’s safe or it’s redundant or – whatever.

Anyway, I tried to build a delirium and improvise-based [mtg_card]Approach Of The Second Sun[/mtg_card] deck.

[d title=”The Improvised Approach” style=”embedded”]Win Conditions

1 Approach of the Second Sun

Controlling The Game

4 Reverse Engineer

4 Commit // Memory

4 Cast Out

4 Farm // Market

2 Metallic Rebuke

4 Implement of Improvement

4 Descend upon the Sinful

Mana Augmentation

1 Inspiring Statuary

4 Trail of Evidence

4 Wild-Field Scarecrow

Lands

4 Irrigated Farmland

3 Desert of the Mindful

3 Desert of the True

7 Plains

7 Island[/d]

This game’s win condition – broadly speaking – is firing off an Approach of the Second Sun, then hold the game under your thumb for a mere seven draws, then do it again. The issue is that it’s designed to make sure your win condition is redundant and safe and protected – which means using Memory to reshuffle it if it’s countered, using your own counterspells to protect it, and firing it off after you’ve thinned your deck of things like Aftermath cards and put all the lands on the battlefield.

This deck is kind of fun.

Once.

Then, if you’re like me, you finish playing it, you set it aside and you never want to look at it again. Because how many times in one game can you want to cast Approach? I’ve had a counter fight and clue token accumulation result in one turn featuring three castings of the same Approach.

This is a surprisingly resilient casual control deck. You can buy the whole thing for ten bucks and you’ll have a deck that works just fine and the pices within it will even be somewhat redundant – you’ll have a use for other applications of the cards that cost more than a cent.

But oh my god am I done with it.

The Four Jaces

In Magic: The Gathering, there’s a character called Jace Beleren. You probably have heard of him. You really have if you’ve hung around me for any length of time, because I tend to make fun of him a lot. Yet for all that I talk about him, I very rarely talk about him. I tend to just make fun of the concept of him, and that’s meant to be funny in and of itself:

Also “What’s Jace up to? Let’s Check on Jace!” and “Jace Died On The Way To His Home Planet” https://t.co/8nr9zDSiUh

— Talen Lee (@Talen_Lee) January 13, 2017

Jace is a character pulled between an unfortunate series of limitations and I think it’s worth my time to sit down and actually address them – because there is not one Jace that we talk about. There is a complicated, intricate web of Jaces. Come with me, beyond the fold, to the Jaceception.

Continue Reading →Game Pile: Transformers Devastation

In October 2015, a new Transformers Videogame hit the shelves and it read like the kind of thing a fan would have made up – a full-scale brawler game, modelled on the classic G1 aesthetic, rendered in tight cell-shaded styles and delivered to us courtesy of the minds behind such classics as Vanquish and Bayonetta: Platinum Games. It had a frightfully short hype cycle, too – it was announced in June 2015, and launched less than three full months later.

So what came of this? Did the game actually deliver on its incredibly strange, moment-in-time development? Was it a cheap cash-in on a license that was in the news? Was this just another attempt to mine our nostalgia?

Notes: Secrets

- Hidden identity small-box game

- The materiality. Tokens can’t be mistaken for cards can’t be mistaken for the mat for the arrows.

- Observing it seems too much of the game is invisible

- Ways to keep people engaged in the off-turn

- The draw-and-share cards mechanic is appealing based on games like Secret Hitler too, I like that

- Can the game be handled with a low-material tool for agreeing/refusing?

- Think about this in light of HMS Dolores–

- Oh they made Dolores

- Well then

- Oh they made Dolores

- Aesthetic is super important, lots of cool, vibrant art, minimal background work

- Giving people positive/negative score cards/trying to force busts/breaks

- Alternate mechanism ideas?

- I expect I’ll try doing something with this – the secret identities/common pool of cards thing is very desireable, but it needs to have some extra way to get some teeth

Setting Your Own Goals

I’m job searching right now, working on finding some work leading up to the new year. It sucks, trust me. Today – when I wrote this, not when this goes up – I did a bunch of things.

- I did a preliminary rulebook for Sector 86

- I contacted a number of businesses about job opportunities (five)

- I cleaned up the house

- I brought in the laundry

- I wrote three articles for the blog (which is why this is so far ahead!)

- I developd a schedule for posting MTG stuff to my blog

- I had lunch

- I walked the dog

- I gave the dog his worming tablet

- I made a slow-cooked dinner for Fox

- I updated my blog’s opening presentation, which is like, a resume element

- I set up a twitter for a new podcast that’s coming

- Tried to do more work on my PhD submission

And despite all that, I’m sitting here, at six pm, fizzing quietly, and wondering to myself… have I done enough today?

I’m not feeling great these days. I’m riddled with anxiety and I’m stressed and I’m feeling unproductive. But when I sit down and write out a list of things I did today, it always is that I ‘waste’ a lot of time doing things.

It’s hard.

You have to get into the habit of determining what your goals are. You have to be able to set yourself limits and say today I’m done with this.

Designing A Puzzle

Some games are designed to be about setting up a play space, where you can sort of simulate a thing interacting with another thing. Games like Wobbegong-12 are about that very pure experience of a thing, in a place, doing stuff. Other games, though, are much more about a puzzle.

Recently I designed a game called You Can’t Win. The game got its start as originally, a conception of a bunch of villains siting around playing Russian Roulette, flipping cards from a small deck of 6 cards and shooting themselves. My efforts to refine this, to make the rest of the game engaging, required a more and more elaborate game, until finally, I realised, I had a puzzle that didn’t need the Russian Roulette mechanism.

What I was left with was a trick-taking game, and I found, my original idea to play it was breathtakingly hard to win. That sort of played into the idea of You Can’t Win and eventually gave the game its name.

The nature of You Can’t Win is one where, the first time you play it, nobody wins. Probably. It’s very, very easy to knock out all the playable numbers the first time you play. The tactical choices aren’t obvious – and in a game of say, four people, you only ever get to make four or five choices of what to play, which means your options are very limited.

Most players play a round or two of You Can’t Win and decide they think they know how hard it is, how difficult it is to play, then decide they’re not interested. That’s fine. It’s a cheap little game, it’s meant to be something niche. But, but.

For a particular type of player.

I’ve watched it happen. It’s that special character of that one person at church youth group, the teacher, the guy who remembers all the tiles in Carcassonne. It’s the mindset that you look at your card, you look at your hand, and you start trying to map the puzzle in advance. As the game gets played, more components of the puzzle play out. You know what’s in your hand. You know what’s not in your hand. You know you’re less likely to see a concentration of numbers, you’re more likely to see them spread out, but you might not. You know there are guns in the pool, too, making wild cards.

And for that kind of player, it is wonderful to sit there and chew on the puzzle. To grind it in their head. To try and properly solve the game… and watching as those players fight against one another and adjust the puzzle is fascinating fun.

It’s okay if what you’ve crafted is a nasty little knot of a game, basically.

New Shirts! Paragon City College Shirts!

Hey there friends! Do you remember City Of Heroes, and its many different university campuses, where you could go to craft inventions in a relatively peaceful environment, without fear of being shot at? Well, we have some cool t-shirts designs you can wear to signify your affiliation with one of those places!

Founders Falls was the oldest suburb in Paragon, and apparently, one of the snootiest. It had canals and bridges and arches, and was proud in the esteemed age of the area. It also had snipers in suits on the rooftops, which was a thing.

Steel Canyon was your lowest-level University you could access, heroside. It was a region full of skyscrapers and powerful businesses, with a self-image about being forward-thinking and recovering after the Rikti War.

Did you know that City of Heroes had a Creepy New England Town? And that town had a whole university in it? Check it out!

Blueside didn’t have the only Universities in-setting. Also, redside, Cap Au Diable, the personal domain of an evil super-scientist named Doc Aeon, had a university too!

And finally, here’s a little special one for the Kings Row diehards. Sure, we didn’t have a university, but we had spirit, damnit!

These designs are available as shirts, mugs and stickers on my Redbubble store. Please, do go and check ’em out!

MTG: GW Delirium

This week, I’ve been playing a green-white brew, based on watching the coverage of the pro tour for Eldritch Moon. I saw the Owen Turtenwald deck that was using Delirium along with Grapple with the Past to fuel a really cool, spicy toolbox kind of deck.

Now, the rewards for delirium in that deck were Grim Flayer and Emrakul, The Promised End. Grim Flayers are out of my pay grade and Emrakul has been banned (and even then is still out of my pay grade), but I did find a few cute little synergies in a deck I have labelled, somewhat unimaginatively, ‘GW Delirium.’

[d title=”GW Delirium” style=”embedded”]Threats

4 Sunscourge Champion

4 Gnarlwood Dryad

3 Honored Hydra

2 Adorned Pouncer

3 Mouth/Feed

3 Pilgrim’s Eye

3 Mockery of Nature

Tools

4 Grapple with the Past

2 Nature’s Way

3 Descend upon the Sinful

4 Cast Out

1 Forsake the Worldly

Land

4 Scattered Groves

4 Desert of the True

4 Desert of the Indomitable

6 Plains

6 Forest

[/d]

Threats

Let’s run down the threats real quick because oh my goodness we have some lovely stuff here:

Let’s start with the simplest creature. The Adorned Pouncer is just a 2-drop body that Eternalizes well. It’s not like this deck does anything to buff it or prepare it, but it does do a good job of bearing in the early game, scoring a few early beats or blocking an early problem. It dies easily, but you don’t mind if it dies! Late game, an Eternalized Adorned Pouncer – which you can get in the yard by a whole host of means – is a really scary threat.

Basically, it’s cool, but it’s also not amazing. It fills out the early slots and sometimes in an attrition fight, comes out of the bin and just wins the game on the base of being enormous and your opponent has simply run out of removal.

From blatantly powerful to deceptively powerful, Mouth is a creature that dies to Fatal Push but otherwise does the job of most any other 3-power card. It gets in fights, it rumbles in, and it feeds, of course, Feed, letting me draw an extra card. Feed’s synergies are a little cute in this deck; it draws cards off Eternalised (with an s) creatures, it draws cards off Delirious Gnarlwood Dryads, and it draws cards off the Angel token you get from Descent Upon the Sinful.

If you can Feed for 2 creatures, that’s good. Remember, you’re casting it out of your graveyard and that means it’s -0 cards in hand for +2 cards in hand. Ancestral Recall is -1 card in hand, +3 cards in hand, for the same net value. If an opponent kills something in response costing them a card, that’s still -1 card from them for you. Still hurts, but don’t stress too much about it.

(I know it’s not as good as Ancestral Recall, don’t @ me).

This is a weird one. It’s not really the perfect Emerge creature – I think I’d probably rather almost any of the others except It Of the Horrid Swarm, because the mana curve goes more smoothly from 3-drop to 4-drop, eating my 3-drop. Adding blue to the deck would give me room for Wretched Griff or Lashweed Lurker, both of which are kinda spicey and solve different problems, but, Mockery originally got put in this deck as a removal card.

Note that Embalm tokens don’t have mana costs, so they don’t reduce the price on this. Which is super annoying!

Also, it has some very cute synergy with the next threat, where…

The hydra is good embalmed, and good played from hand. Played from hand, you can play it, attack with it, then Emerge a Mockery and embalm the Hydra on the same turn. The Hydra is also just, y’know, huge? Sometimes you just want a big trampler. Given the way this deck tends to work, with the late game about threats that are hard to permanently deal with, the Hydra is a perfect example of what you could be spending six mana doing.

This card puts in some work. I like how it works with Nature's Way, but it also just servess as a super cheap little aggressor in the early game that’s fiddly to block and sometimes can inflate into a 3/3 when you need to put pressure on fast. Sometimes you need a thing to hold the ground against very scary threats and it’s hard to do better than something so cheap as this.

And boy howdy, here we get to a card I’m still startled is so very, very good. Discarding a Sunscourge Champion to eternalize another Sunscourge Champion feels gross, and then you’re basically turning a card in your hand into an uncounterable Loxodon Hierarch. This card also feeds into Emerge nicely – another build of the deck with Wretched Griffs and Vexing Scuttlers happily traded this card into the bin for an extra card. Oh the value.

Tools

The removal/card advantage package is designed to be a decent mix of things to enable delirium easily – you can cycle a cast out or sacrifice a Pilgrim’s Eye to get two of the rarer types of cards into the bin really quickly. Cycling lands do that too – and cycling lands mean that Grapple With The Past, even when it misses, doesn’t quite miss.

The big thing with this deck is just the room in it. You can cut a bunch of the cards because you may not like them as much as I do, but you need to be able to point to some things your deck can do that you do like. For example, I love Nature’s Way, which is just super sweet to use with a Gnarlwood Dryad or an Eternalized Adorned Pouncer. I like using Feed to draw cards. I like the mana base and I love that this deck can pack a Wrath effect as a way to make a threat. It’s great fun doing a bunch of trades, letting your first-round creatures hit the bin, swapping for removal, watch your opponent build out their board…

Then Descend, and add 4/4s alongside your 4/4.

Also, this deck folds to Turbo-Fog, which you will see in the casual room.

Price

MTG Goldfish price this deck at 5.17 online, $22 offline, and I think that’s a pretty reasonable rate for a deck that’s just, you know, fun? It’s hilarious to me that you generate a giant pile of rares and they’re all… rubbish rares?

Wrapup And Alterations

If you wanted to shift it into Bant colours, you could add the blue emergers, like Wretched Griff, ditch the desert cyclers and replace them with the UW cycle land – There’s something there. It’s interesting. It’s a maybe.

Anyway, this deck is fun. It’s a sluggish midrange deck that gains tons of life and occasionally blows people out with cards they forgot existed, and there’s lots of room for customisation. It’s resistant to countermagic thanks to mechanics like eternalize and embalm, and aftermath and Grapple let you treat your graveyard like a backup hand.

Roads Unbent

I grew up – okay, let me start that again.

I lived, from the age of four to the age of fourteen, in a suburb of New South Wales called Engadine. Engadine is where I learned how money works, how to read, what a library was, how to talk to a doctor, about family restaurants and VHS tapes and watched the Beta cases slowly disappear off the shelves. It’s the place I walked with my mother as she went to a business to pick up an actual physical paycheque and hand it into an actual physical bank. It’s the place I tried a paper route.

To say I ‘grew up’ there is a misnomer, though. Because in Engadine, I was in an environment that deliberately sought to stifle what I learned of the world, watching a small number of years left in the world tick down. But Engadine is still a big part of my life, and time to time, we pass through it on the way to Sydney, from where I live now.